The career of artist Alberto Guerrero has been driven by an overarching desire to look for what is behind everything that we merely, and only dimly, perceive at present. The work of the forty-something Madrid-based Guerrero ranges from abstract, highly textured canvases and three-dimensional images which he calls “spherical paintings” to realistic presentations of daily life — such as his illustrated book Diary of a Quarantine showing life in the Guerrero household during Covid — and deeply reflective images of sacred art. There are few contemporary artists who have such a broad range and vision.

At Guerrero’s studio, located in a somewhat scruffy area of Madrid far from the tourist traps that line the Plaza Mayor, one enters a large industrial space that would once have been used for manufacturing, legal or otherwise. It looks something like a large mechanics’ garage, rising two stories and punctuated by skylights.

At the far end, bookshelves crammed with volumes rise nearly to the ceiling: artists’ monographs and books on movements in art history, all of which are crowned by a faded sign depicting the Google logo. This painting, one of a series which Guerrero executed as a “vanitas” contemplating big-tech companies, and the only one he kept for himself, marks a kind of analog Google library, which the artist uses to enrich his understanding of the past.

“I’m very interested in history,” Guerrero explains, “because I strongly believe in the connection between the past and the present. It’s reflected in my paintings, because the way I paint is to superimpose different layers in order to create a harmony.”

Guerrero’s paintings, which are often quite large, can be difficult to capture effectively in photographs, because many of them are three-dimensional. These pictures are also saturated with layers of color, created using a slurry of material such as cellulose mixed with pigments and suspended in a latex binder. Their surfaces ripple and twist and contort, as the light striking them shifts and changes.

Like the Dutch and Flemish Old Masters, Guerrero uses marble dust rather than preparing the surface of his canvases with a simple wash or gesso. “I use a very fine grain of marble dust because of that granular quality,” he explains, “and because it’s very white. I’m interested in creating light and depth in these works.”

These two elements, light and depth, are recurring themes that one perceives in his highly varied art. “I want to suggest that there is something behind all of this,” he explains. “You don’t know what it is, but there is something there. So I try to suggest that something in the way that I paint, as I want to talk about how the something that is behind and bigger than the painting itself can be perceived, paradoxically, by showing a fragment of the thing which is in fact much larger or partly hidden.”

The saturated colors and tones in these paintings are breathtaking in person, almost like seeing color for the first time. This effect is intentional. “We forget, for example,” he notes, “that until the arrival of cheap chemical processes to create colors during the nineteenth century, that to see something painted in aquamarine blue was a visual experience that was completely extraordinary for most people. Colors were luxuries, and we don’t think about color that way anymore. The impact of color on someone who was living surrounded by rusty browns and ochers and so on — to suddenly come across bright colors was a tremendous experience. In the past, the color palette available for the average person was highly limited, so to come into a public building like a church or town hall and see it decorated with all these spectacular colors must have made a huge impact.”

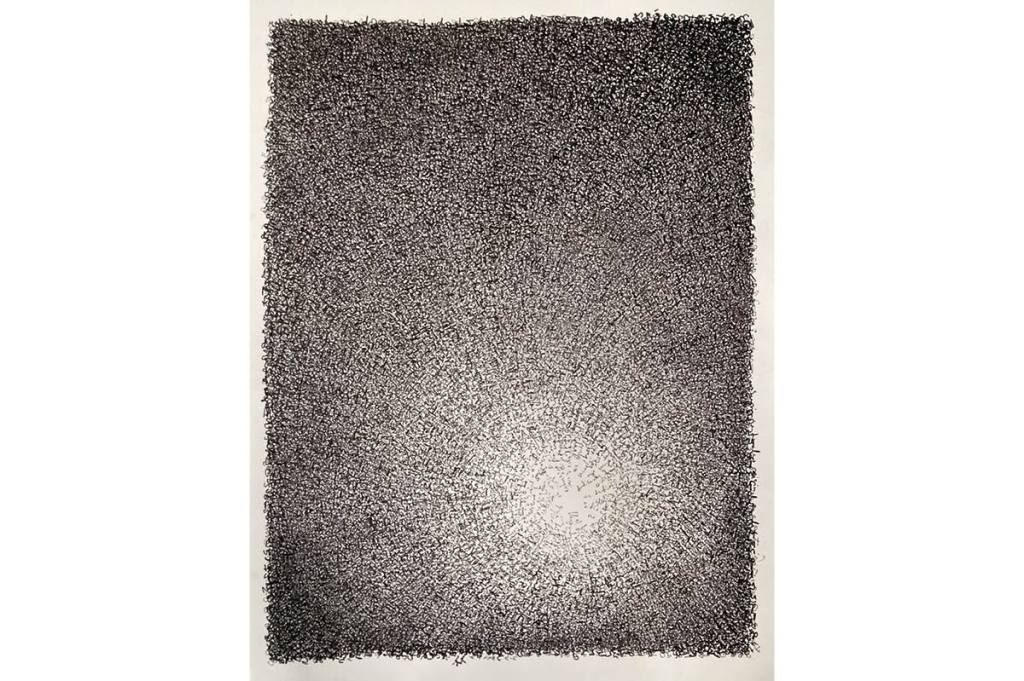

In another corner of the studio, large sheets of cotton paper are covered with hundreds of words written on top of each other in a swirling, spiral pattern. A few of the words are still legible, expressing feelings and thoughts that the artist was experiencing during a time of great stress. Not simply meaningless and jumbled text, they form a kind of path by which to escape from the chaos and noise they represent. The largest carries the title, “In Search of Silence,” and is a 2D interpretation of how worry and anxiety can often feel. “You can’t ‘read’ this work,” Guerrero explains, “but it has meaning, even if you can’t actually make out what it is saying. I’m looking for the center here, where there is quiet and light, and everything outside of that center is just noise.”

Leaving the studio, we travel to a completely different area of Madrid: the neighborhood surrounding the Bobath Foundation, which is lined with leafy streets filled with attractive housing. Guerrero was commissioned to decorate the new chapel at the Foundation’s day center, which was recently consecrated by the Cardinal-Archbishop of Madrid. The planning involved working within clear parameters, designing the space with respect to those who would end up using it, children with cerebral palsy. Because many who visit the center use wheelchairs or need other assistance, this could not be a standard chapel design with fixed pews and a central aisle, but needed the ability to be reconfigured to serve its visitors.

Yet if rich colors and textures categorize many of Guerrero’s abstract paintings, this chapel has a celestial yet simple quality, unexpectedly from an artist whose work is often so highly earthy and tactile. Here, the palette is limited to whites and beiges, alongside a profuse use of gold. The sanctuary wall, for example, is covered in hundreds of squares of gold leaf, so that with the light streaming in from the windows the effect is mesmerizing, a kind of Byzantium when it was new.

“In all of the sacred art that I do, I like to involve the use of gold,” Guerrero explains, “because of the symbolism and the tradition in using it, such as in the iconostasis one sees in Orthodox churches. Here in the sanctuary, there is gold because it’s the sacred place where God makes himself present: it’s a way of marking that presence and that dignity, and gold as a material itself is somewhat mysterious and yet warm, not cold or distant.”

The main art object in the chapel, and the largest work created for it by Guerrero, is his painting of the Crucifixion. It is simple but realistic, and very direct, referencing the Shroud of Turin — it depicts the nail piercings through the wrists rather than through the hands, for example, and recalls the Shroud in its rendering of Christ’s hair and the crown of thorns. To Guerrero, the juxtaposition of celestial gold and earthly imagery serves as a paradox, something he tries to explore in his sacred art as much as in his secular art. “For me in this space,” he explains, “here is the paradox: the image of the Crucifixion which provides the realistic contrast representation of Christ’s sacrifice in this world, and the mystery of the surrounding gold evoking another. The salvation is real, but it is brought about through the mystery of grace.” For someone who is often thought of primarily as an abstract artist, Guerrero is very conscious of the fact that abstraction is not the end-all-be-all of contemporary art, certainly not in a place like this. As he notes, “This art has to help the person to try to understand what is happening here, what is behind and beyond what we perceive.”

Seeing this profoundly meditative space, so unexpected from an artist who creates enormous canvases that may look like the hot, cracked surface of a Castilian wasteland, or the view of the surface from beneath the waters of the Mediterranean, was further proof of the fact that Guerrero has never felt confined by the expectations of an art market or intelligentsia primarily interested in artists fitting into a predetermined narrative.

Later, over lunch at his home, Guerrero reflected on some of the pitfalls the contemporary art world has not been able to address. “A lot of contemporary art falls into the trap of only talking about itself,” he suggests, “and it becomes a product of the elite, or only for the elect. And in the end, if you are not of the elect and if you question it, then they ask, ‘And who are you? You’re not a part of the club.’”

Part of the issue, Guerrero believes, comes down to the shallow, endlessly self-referential aspects of our contemporary society. I ask whether this is because people today have more time on their hands, since their lives are less hard or sad than in the past. “I don’t think that people of the past were sadder than we are now,” he observes. “In fact, I think today people are more sad than they used to be. Life was harder in the past, absolutely. But sadder? I don’t think so. Art is such a good reflection of what people think and what they value in the age in which they are living,” he continues, “and it’s interesting that I see a greater amount of joy overall in the art of the past, than I see in most contemporary art.”

Guerrero also believes that a shallow artistic facility that substitutes for depth is part of the problem. “If you have the ability to communicate, but there isn’t much of anything behind it, just presenting yourself, then you end up with a kind of formalism, and an art that is, frankly, empty. It may look spectacular at first, but later you realize that there isn’t really anything to it, which is very sad because in the end, one loses the sense of what art is for: that ability to communicate something that is fascinating, yes, but that is also greater than oneself.”

Unlike many successful artists, Guerrero prefers self-effacement to self-aggrandizement. “We have mysticized the figure of the artist to such an extent, that when people go into a gallery or museum they treat it as if they were going to a place of worship, with a reverential silence so hushed that people are more well-behaved in a museum like MoMA than they are in the cathedral of Toledo. And for what? Because ultimately, this individual person whom you have sanctified because of his art is just a person. Everyone has the possibility of expressing themselves in some form of art, but if we treat particularly talented artists like saints or divinities, then the end result we have now is inevitable.”

Guerrero doesn’t appear to be particularly concerned, however, because he takes the long view that good art will eventually win out over bad. “When art is good, when we feel a real connection to it, then it doesn’t matter if it’s five or 500 or 5,000 years old,” he reflects. “When art connects us to our reality in a deeper way, and we see that there is more going on behind the art, and behind what we are experiencing ourselves, then that for me is the whole point of art. And in my own way, that is what my work is trying to do.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2023 World edition.