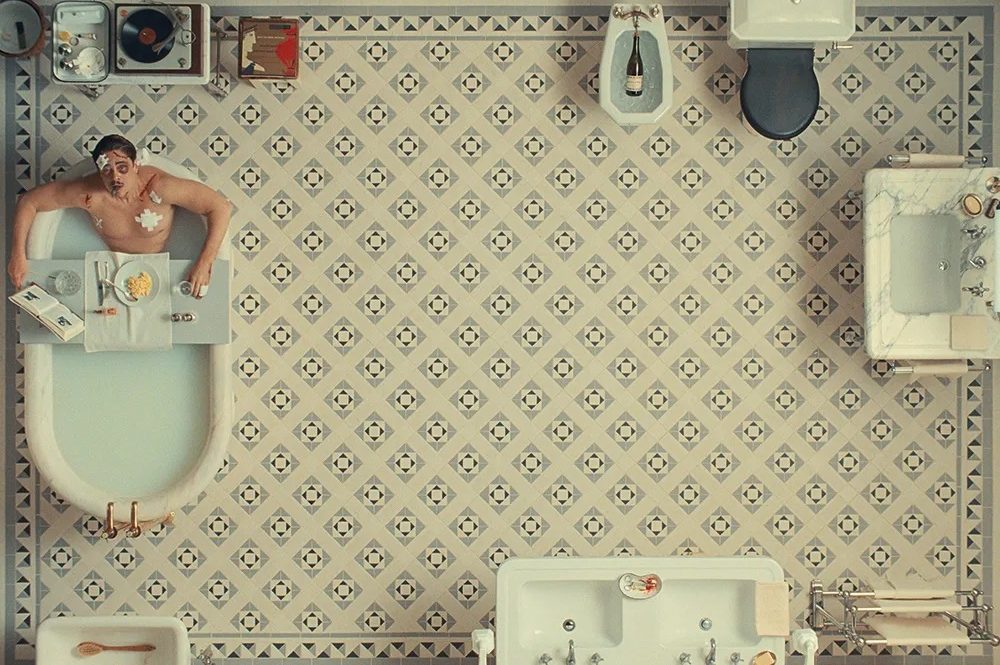

Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire is set on a remote, windswept Brittany island in the late 18th century. It’s about two women falling in love and it’s rapturous, scorching, ravishing and will lock your eyes to the screen. I’ve seen it three times and on each occasion my eyes were locked to the screen. At this point I could also say it’s a film that tells the male gaze to go take a running jump, then follow up with one of my lectures on post-structural feminism, as I know you are keen on all that, but ‘rapturous, scorching and ravishing’ will do for now. Plus it is deeply romantic. And wildly sexy. And, my God, so full of feeling. So let’s just go with all that.

Noémie Merlant stars as Marianne, an artist employed by a countess (Valeria Golino) to paint her daughter Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) on that windswept island. Héloïse is betrothed to a Milanese nobleman but before the marriage can proceed he must see a portrait because that’s how it worked before Tinder. However, there is a problem. Héloïse’s older sister was similarly betrothed but fell to her death from a cliff — or did she jump? — and Héloïse has thus far refused to be painted. So Marianne, who arrives in the guise of a walking companion, must observe her closely and then paint later in secret. Marianne looks. And looks and looks and looks. Until, finally, Héloïse looks back. It is all in the looking, and in looking at the looking we are taught to look too. I don’t, for instance, think I’ll ever be able to look at an ear again without taking note of its ‘warm and transparent hue’ and how it must ‘yield to the cheek’. In fact, I haven’t stopped looking at ears since.

Sciamma, who also wrote the screenplay, has created a film of patient tenacity as longing and desire slowly build. There are no men to speak of and, with the countess away on a trip, that leaves just Marianne and Héloïse in the house along with the servant girl, Sophie (Luana Bajrami). They play cards, share meals, smoke pipes — Marianne is fond of a pipe — and read Ovid in the evenings as that’s how it worked before Netflix. Here, women’s bodies are not idealized, so, interestingly, it’s periods, unwanted pregnancies, armpit hair. Yet while there are no men, their power is everywhere. Héloïse must accept her matrimonial fate. Marianne can only exhibit under her father’s name and is not allowed to study the male nude form. (‘Is it a matter of modesty?’ asks Héloïse. ‘It’s mostly to prevent us doing great art,’ replies Marianne.) But Sciamma is so smart, and the characters feel so true and real, that none of this feels like the feminist dogma you are so keen on. In fact, the two leads inhabit their characters so fully it’s as if they are not acting, even though you know they are.

Portrait is a film about what it’s like to truly see and be seen, and while never melodramatic, it does culminate with a crescendo of feeling and if ‘page 28’ of Marianne’s sketchbook doesn’t break you, absolutely nothing will. I was going to add that you’ll understand if you go and see this but there must be no ‘if’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.