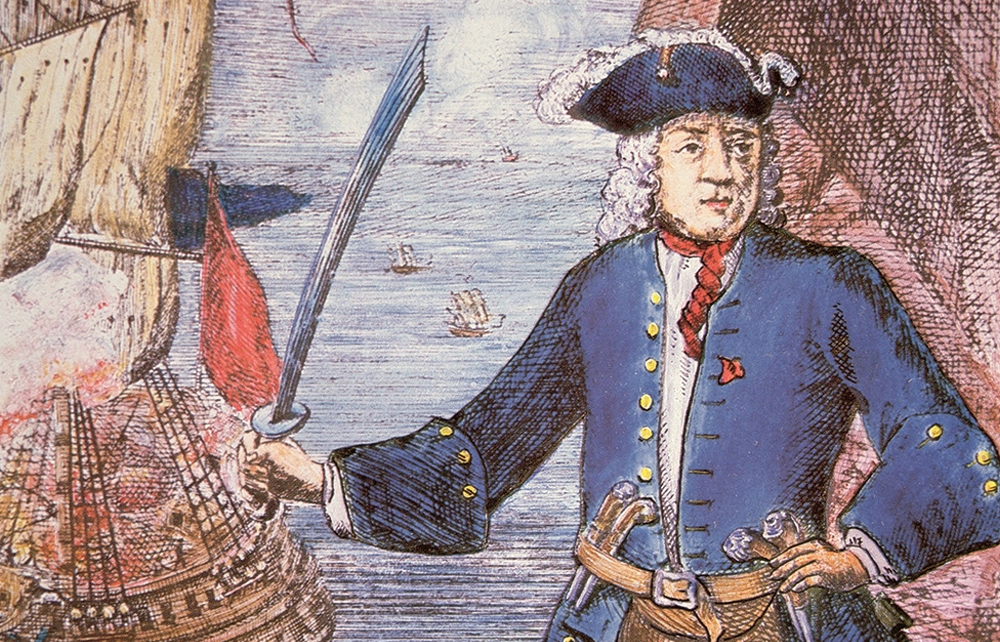

On September 7, 1695, the twenty-five-ship Grand Mughal fleet was returning through the Red Sea after its annual pilgrimage to Mecca when it was attacked by five pirate ships. In the ensuing battle, the pirates’ leader, an Englishman variously known as Henry Avery, Henry Every, the King of Pirates and Long Ben, seized precious jewels and metals worth £600,000 — equivalent to around $118 million today.

The furious Mughal emperor Aurengzeb accused Britain of complicity in the raid and threatened to expel East India Company representatives from India. The British government, seeking to appease the emperor, launched the first international manhunt, declaring Avery “an enemy of all mankind.” The pirate booty was never recovered, nor, while six of his fellow pirates were hanged, was Avery ever brought to justice. One story has it he was buried a pauper in Barnstaple.

The late American anthropologist David Graeber preferred another story. According to this saltier yarn, Captain Avery sailed off victorious on his fifth-class frigate Fancy, with not just a haul of unimaginable bling, but with the Mughal’s daughter, her head turned (whose wouldn’t be?) by this sexy outlaw. More captivating still, the story has it that Avery and his princess bride, along with 10,000 of his henchmen, then established a pirate kingdom in Madagascar. This realm, called Libertalia, was, according to Graeber, a utopian polity wherein all goods were held in common.

From his Malagasy throne, Avery despatched envoys to the courts of Europe, duping the Swedish crown into signing treaties with this purported great new power of the Indian Ocean and even inducing Peter the Great to contemplate an alliance, and create a Russian colony on Madagascar. The Czar should have known better after his predecessor, Catherine the Great, had been duped by Potemkin villages. Peter was effectively fooled into believing in the existence of a Potemkin kingdom, all front and no substance, on the other side of the world. Only in 1719 was the hoax exposed by Daniel Defoe in his superbly titled The King of Pirates: Being an Account of the Famous Enterprises of Captain Avery, being the mock King of Madagascar with his Rambles and Piracies wherein all the sham accounts formerly publish’d of him are detected.

And yet Madagascar’s northeastern coast for decades afterwards continued to attract pirates, who established trading posts for like-minded bucklers of swash that evolved into what Graeber calls Libertalia II — namely the Betsimisaraka confederation. He writes:

The toothless or peg-legged buccaneer hoisting a flag of defiance against the world… is perhaps as much a figure of the Enlightenment as Voltaire or Adam Smith, but he also represents a profoundly proletarian vision of liberation, necessarily violent and ephemeral.

Graeber’s suggestion is that the egalitarian values that he argues thrived aboard pirate ships came ashore and flourished for a few decades in a remote corner of a remote island. A utopian political experiment was led by charismatic pirate captains collaborating with Malagasy warrior kings who, despite their titles, were part of a society of equals.

To sustain this narrative, it’s important that Avery, like many pirate captains, was elected. Indeed, the year before the raid on the Mughal fleet, he had been a mate aboard the privateer Charles II, whose crew mutinied over meager pay and voted for Avery to become their captain. In that role he changed the ship’s name to Fancy and headed off for adventures involving purloined princesses, make-believe kingdoms, sea battles, poisonings, jewel thieves, magic spells and sex. Not that the pirates whom Graeber describes were lovable rogues. In the topsy-turvy seventeenth-century world in which piracy was a hanging offense but slave trading was perfectly legitimate, many pirates had a sideline in slaves, the legal front masking piratical criminality.

Graeber doesn’t say whether Avery raised the Jolly Roger, but he does meditate intriguingly on the fact that in some iterations the pirate flag included not just a skull and crossbones but also an hourglass. For Graeber, the timepiece not only spelt death to foes but signified the pirates knew they themselves were on borrowed time before reaching their final destination, hell. It’s a theme developed in Taika Waititi’s new TV pirate comedy drama Our Flag Means Death. Whether the present-day pirates striking terror into merchant sailors from the Red Sea to Madagascar have the same mindset is unclear.

One can understand why Graeber would be drawn to the legend of Libertalia. Until his death in 2020 at the age of fifty-nine, he was an antinomian buccaneer himself, effectively banished from American academia for his radical views and his participation in the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011, pitching up on the more welcoming shores of the London School of Economics. There he wrote books such as Bullshit Jobs, Debt and the 700-page The Dawn of Everything, published posthumously last year. In this, he and his co-author David Wengrow ranted against the oxymoron of western civilization and eulogized the possibility of creating the post-bureaucratic egalitarian society.

In Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia there is a will to believe that something like such an egalitarian society existed in seventeenth-century Madagascar. But for Graeber, Libertalia wasn’t the invention of European pirates, but one in which pirates worked in tandem with Malagasy political figures and in which women played unprecedentedly key roles.

Perhaps the book will become required reading for liberal arts undergraduates taking the “Queering the Enlightenment” module, but it is a heroically unreliable guide to a barely documented historical incident. A chapter on the advent of the pirates seen from the Malagasy point of view is nothing of the kind. There are no contemporary Malagasy sources to draw on, only more or less fanciful and racist European versions of what, if anything, took place. Graeber’s account of how women were emboldened by interloping pirates to subvert the Malagasy patriarchy by marrying foreigners and deploying love potions and poisons to bend men to their wills makes a fascinating story, but it doesn’t ring true. We’re in a hall of mirrors, a world of speculation where what might have happened, what Graeber hopes happened and what actually happened are tied up in the kind of nautical knot that never comes undone.

On Île Sainte-Marie, just off Madagascar, there is a pirate cemetery, where perhaps Avery’s remains lie rather than in Devon. Graeber has put flesh on those bones and brought them back to life. His first anthropological fieldwork, in the late 1980s, concerned Malagasy divine kings, and this, his last book, invites us to reimagine Madagascar as more than an island of lemurs, vanilla, baobabs and orchids, but as an Enlightenment crucible, as worthy of note as Philadelphia, Königsberg and Edinburgh. Whether it was is almost beside the point. Like any pirate worth his salt, Graeber spins a spellbinding yarn.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.