In everyday life — on a garden path, flowerpot or lettuce — I back rapidly away from slugs. I didn’t expect to confront them in literature, but in Michele Mari’s Verdigris they are present in abundance, from the first line:

Bisected by a precise blow of the spade, the slug writhed a moment longer: then it moved no more… slimy shame transformed into splendid silvery iridescence

So, not a novel for one who shrinks from gastropod mollusks, you would think.

Yet I quickly found myself drawn into a remote corner of rural north Italy in 1969 where a lonely, bookish boy, Michelino, spends long summers with his emotionally unreachable grandparents. His only companion is Felice, the elderly handyman and gardener who wages ferocious daily war against the red slugs infesting the grounds. Speaking a slurred idiolect and scarred, ugly and illiterate, Felice is the unlikeliest of companions for a precocious thirteen-year-old who thinks in abstruse literary allusions. Michelino watches Felice at work, squeezing verdigris to a creamy paste as he prepares the seasonal spraying of the vines, his gnarled hands turning turquoise. “Ye see, Michelin, be like mashin p’lenta,” he explains.

The boy decides to stimulate the old man’s unreliable memory with visual mnemonic cues to fugitive words. At first, it’s an amusing exercise to enliven the boring summer, but casual companionship leads to questions: where did Felice come from? What is his parentage? Curiosity deepens into friendship.

With Felice’s memory deteriorating fast, Michelino tries to pull him back from oblivion, revisiting a dangerous time when Italians and Germans were poised on shifting ground. Between partisans and Nazi collaborators, who could be trusted? Much lies below the surface here — mysteries, betrayal and violent death, all safely entombed in the past until the child starts digging. Piece by tiny piece, Michelino unlocks secrets, hidden rooms and appalling revelations, some of them dizzyingly convoluted. The truth is not always comfortable or comforting. It can be perilous.

The English version of this novel, by Brian Robert Moore, who has also translated Mari’s short stories, is more than a translation. It is an Ovidian exercise, transforming what could have been baffling to Anglophone readers into a rich and captivating narrative with cultural references and jokes all recast to beguile us.

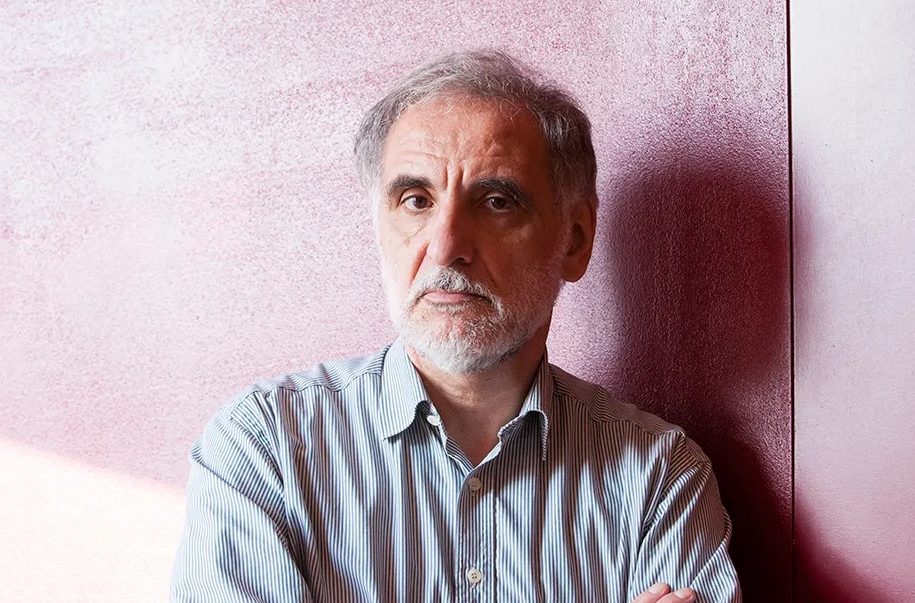

Part gothic fantasy, part bildungsroman, there is a strong autobiographical element to Verdigris. As always with Mari, one of Italy’s leading writers, childhood and memory form a tangled thread. Slugs do, undeniably, play a part, but what shines through is the loving friendship between the boy and the old man, handled with tenderness and warmth.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply