Season four of The Crown begins with the murder of Lord Mountbatten at Mullaghmore in August 1979. Mountbatten was killed with three others, on the same day 18 British soldiers were ambushed at Warrenpoint. It was a devastating blow for the British establishment. But it held a more intimate horror too.

If you listen carefully to the scene in The Crown, you can hear Mountbatten speak to a ‘Paul’ as they prepare his boat, Shadow V, for its fateful journey out of the harbor before being blown to pieces by the IRA.

‘Paul’ is 15-year-old Paul Maxwell, who along with Mountbatten’s grandson, 14-year-old Nicholas Knatchbull, was one of two children the IRA murdered that day in their obsessive desire to assassinate Mountbatten, who had made his summer home across the border in Ireland.

Paul Maxwell went to my old school, Portora Royal, in Enniskillen, a few years ahead of me. Paul gets that one brief reference by name in The Crown and then later, merely as the ‘boat boy’.

I’m not blaming Netflix for this slight. There’s a lot to get through in the same episode, including the election of Margaret Thatcher, Prince Charles’s courtship of Diana Spencer and his sister’s battle to get back in the saddle. But the brief life and brutal death of this 15-year-old over 40 years ago has much to tell us about the appropriation of human rights by those who support and still venerate violent extremism in Ireland.

Only one person was ever brought to justice for the Mullaghmore bombing. Thomas McMahon was sentenced to life imprisonment but was released after 18 years under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.

Unlike other types of collateral damage the IRA sometimes admit to, there was no room for equivocation here. The bombing team watched three children, an elderly woman and a couple get onto the boat with Mountbatten. The bomb the IRA placed on the boat had enough strength to kill them all. The youngsters were expendable.

Terrorists and their contemporary apologists hate their victims being humanized and it is important that we disappoint them whenever we can. Paul’s father John described his boy: ‘He was interested in all kinds of sport. He played rugby, he did all kinds of things. He had a very cheery disposition. He got on well with everybody. He loved the sea.’

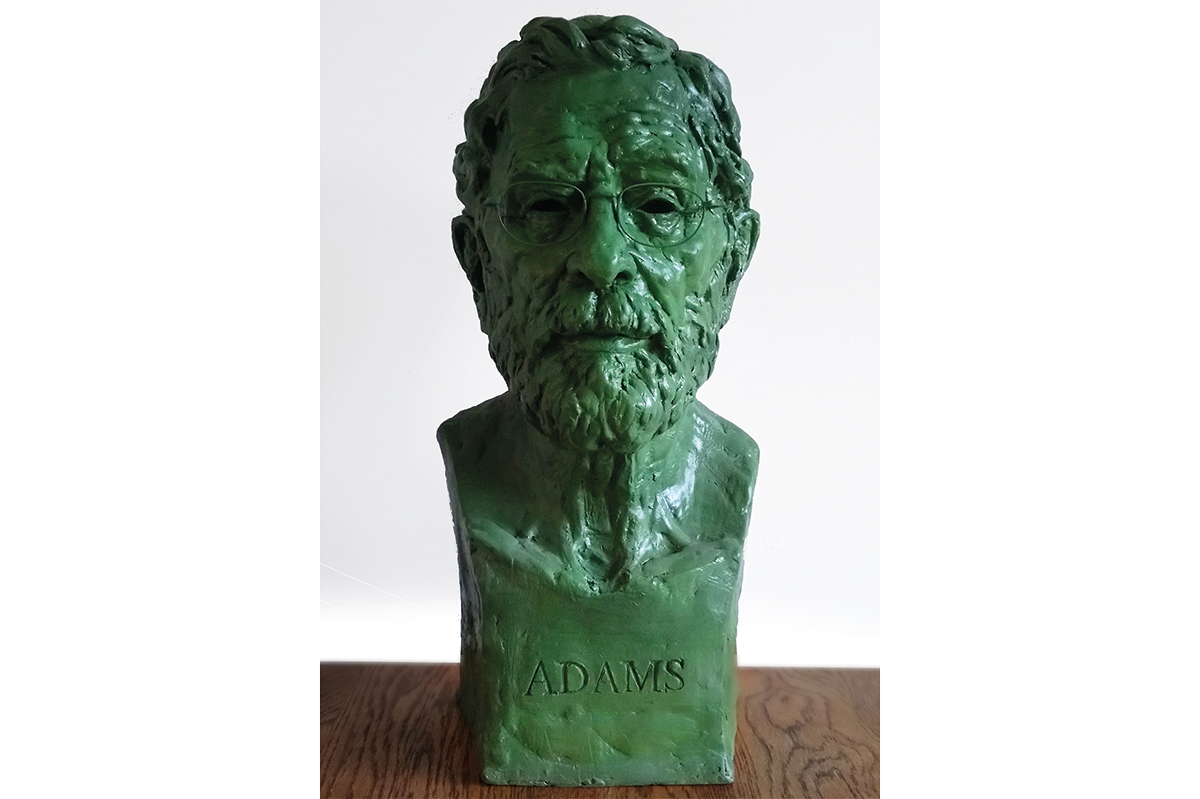

When McMahon was released from prison, he reportedly twice refused to meet with John Maxwell, who simply wanted to try to understand why his son was taken from him. Maxwell was desperate to find some remorse from McMahon to help him rationalize the enormous harm done to his family. None was forthcoming. McMahon later went on to campaign for Sinn Féin at election time. When the party’s then-leader Gerry Adams was challenged over the morality of having a convicted child killer on the campaign staff, he was only able to say that he, ‘values the contribution of every single republican.’

Many of Sinn Féin’s supporters continue to actively venerate people like Thomas McMahon. The vague pieties of regret pedaled by its notional national leader Mary Lou McDonald are designed to conceal the hateful reality to a new generation of young voters that the party was built on atrocities committed before the 1998 Agreement.

For the IRA, the children on board Mountbatten’s boat that day were legitimate targets in the war against the British state. Such grotesque behavior and its defense would surely be something for Northern Ireland’s burgeoning professional class of ‘human rights’ activists to ponder over. But they are in a unification echo chamber and seem to be untroubled by the consequences of such barbarity for any sane version of a shared future.

Things have moved on since 1979. I hope a future episode of The Crown will show how Prince Charles returned to beautiful Mullaghmore in 2015, 36 years on from Paul Maxwell’s cruel death, and the warm reception he received there.

[special_offer]

John Maxwell’s legacy of pain turned into a life tirelessly advocating for integrated education in my hometown where Catholic and Protestant kids are educated side by side in the primary school he founded.

But one party in Ireland remains conspicuously chained to the past. It is fatally contaminated by the delusion that the IRA fought a ‘just war.’ It continues to lionize the ‘patriots’ who chained human beings to bombs, murdered worshippers at church, bombed remembrance Sunday services and deliberately blew children to pieces. It claims to be a party committed to human rights much like an arsonist claiming to be a fireman. It does not ask forgiveness. It does not recognize any shame.

No amount of whitewash or slick propaganda can erase the memory of Paul Maxwell and all the other children who were killed by terrorists in Northern Ireland’s recent agony. Nor should it. The little tragedies tell the biggest truths. Paul was much more than the ‘boat boy.’

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.