I have to laugh when I read about my Baby Boom cohort’s memories of savoring rock ’n’ roll behind the backs of disapproving elders. I had no such problem. I wasn’t especially taken with the new sounds of the Fifties: I was six years old when Elvis Presley debuted on the Ed Sullivan Show. I thought he was vaguely comical. In any case, my parents had resolutely high-minded middlebrow taste in such things, wavering somewhere between Dvorak, Lawrence Welk and Mozart. Rock ’n’ roll was simply out of the question.

Everything else heard in the household — country and folk music, in particular, which my elder siblings’ favored — was tolerated to some degree, but my own secret musical vice was not. I was — I am — a jazz enthusiast. But how did this happen? Both of my parents regarded jazz — indeed, most popular music, especially of the post-war era — with indignant distaste. My scientist father had happy memories of a Thirties excursion to the Cotton Club to hear Cab Calloway sing ‘Minnie the Moocher’, but his happiness seems to have been confined to that excursion. To my lawyer mother, Frank Sinatra was the quasi-delinquent from New Jersey who had lured bobbysoxers into skipping school to hear him perform.

Their attitudes seemed to harden with the passage of time. Growing up, I was generally not permitted to listen to the radio or watch television, lest it interfere with schoolwork; nor was I allowed to play records on the old family player or a new high-fidelity system. The only record-playing machine to which I had access was a superannuated device relegated to the basement. I would slip downstairs, on occasion, to listen quietly to Danny Kaye or ‘The Ballad of Davy Crockett’ or discarded Mendelssohn and Beethoven LPs.

In pondering this ancient personal history, I find myself indebted to a curious source for my introduction to jazz. In 1956 the New York impresario Orin Keepnews (later famous for promoting the music of Thelonious Monk beyond the New York cabaret world) co-produced a 12-album series called the RCA Victor Encyclopedia of Recorded Jazz, which was marketed in weekly installments at our neighborhood grocery store.

For whatever reason my mother purchased the first three albums and then, perceiving that I appeared to enjoy them, declined to acquire the remaining nine. As a consequence, my earliest exposure to jazz was alphabetical: I listened, repeatedly, to the same two-dozen musicians, ranging from Henry ‘Red’ Allen at the start of Album 1 to the Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey at the end of Album 3. Beyond the letter D was an undiscovered country.

Within those three albums, however, I ranged widely. There was early jazz (Sidney Bechet), swing (Bunny Berigan), even mild avant-garde (Al Cohn). Classic (Bix Beiderbecke) met commercial (Hoagy Carmichael) in a memorable ‘Georgia on My Mind’. Even now I cannot hear a take on that song without thinking of Mildred Bailey’s version. I also acquired some unconventional attitudes, preferring the trumpet of Buck Clayton to that of Louis Armstrong.

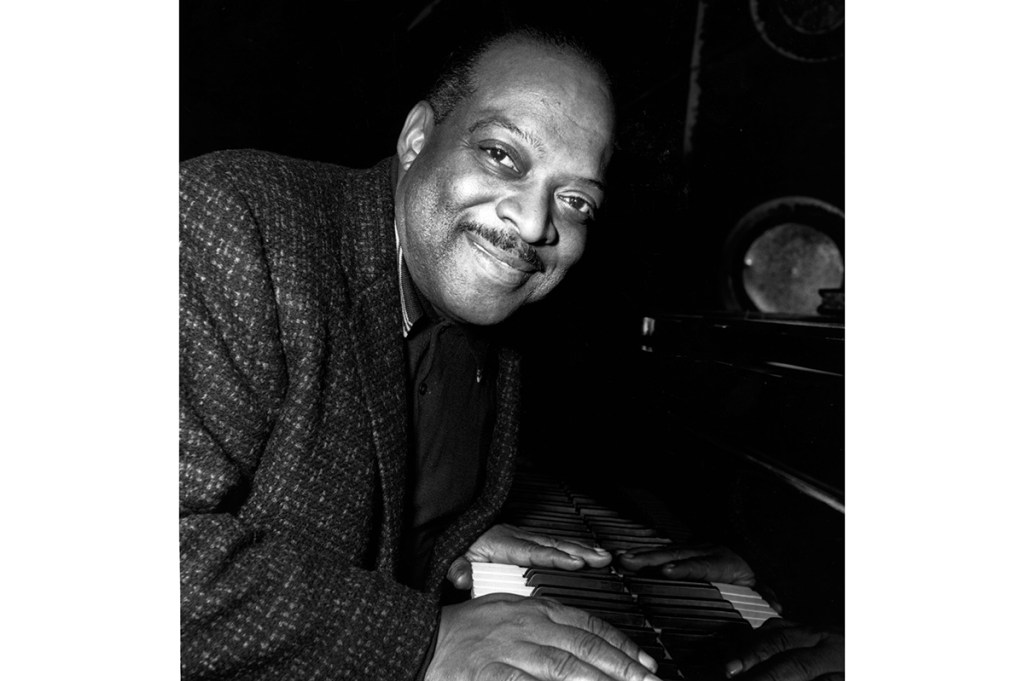

The one piece to which I repaired with obsessive interest — and is now, thanks to scratches, very nearly inaudible — was Count Basie’s 1947 rendition of ‘South’, a long-forgotten number from the 1920s by Basie’s Kansas City mentor, Bennie Moten. It’s classic middle-period Basie. Gently muted brass, mellifluous reeds, alternating soft and intense exclamations, an undulating tenor saxophone solo by Paul Gonsalves, all tightly wrapped in a driving bebop-inflected rhythm.

[special_offer]

What impressed me most was Basie’s piano solo. It lasted exactly eight seconds and, while wholly characteristic of him, was a startling revelation to me. My six-year-old ears were accustomed to Burl Ives, the New World Symphony and TV jingles. Basie’s piano interjections are almost always brief, understated and pulsating: a kind of Emily Dickinson rhyme between the choruses. ‘South’ is typical. With exquisite timing he alternates between a chromatic series of major chords and right-hand octaves, and then runs up and down the keyboard with the band.

I had never heard anything like it. This was not just music as revelation, but liberation as well. Suddenly my own improvised runs and chords, issued largely in response to strict, unwelcome lessons, seemed to point to a trail out of the woods. Discordant sounds could be flavored to taste and the beat was no less important than the melody. Basie’s minor notes, blues inflections and swing affected me viscerally, awakening some latent juvenile synapse. I would play ‘South’ over and over again, and not just on the record machine.

A dozen years later, as an undergraduate, I learned that Count Basie and his orchestra were performing at a dinner club in a neighboring town. Under the guise of reporting for the student newspaper, I made the pilgrimage and interviewed Basie between sets. To my relief, he was cordial and patient and invited me to sit beside him on the bench. I felt obliged to ask him the sort of questions he was accustomed to answering, too embarrassed to confess that it was he who had revealed to me the language of jazz. His solo in ‘South’ still plays — indelibly, perpetually — in my ear.