A narrative biography by a member of its subject’s family is, if not unique, something of a novelty. Here, Christopher Shaw Myers writes the story, while his uncle Robert Shaw’s life (1927-78) provides the book’s framework.

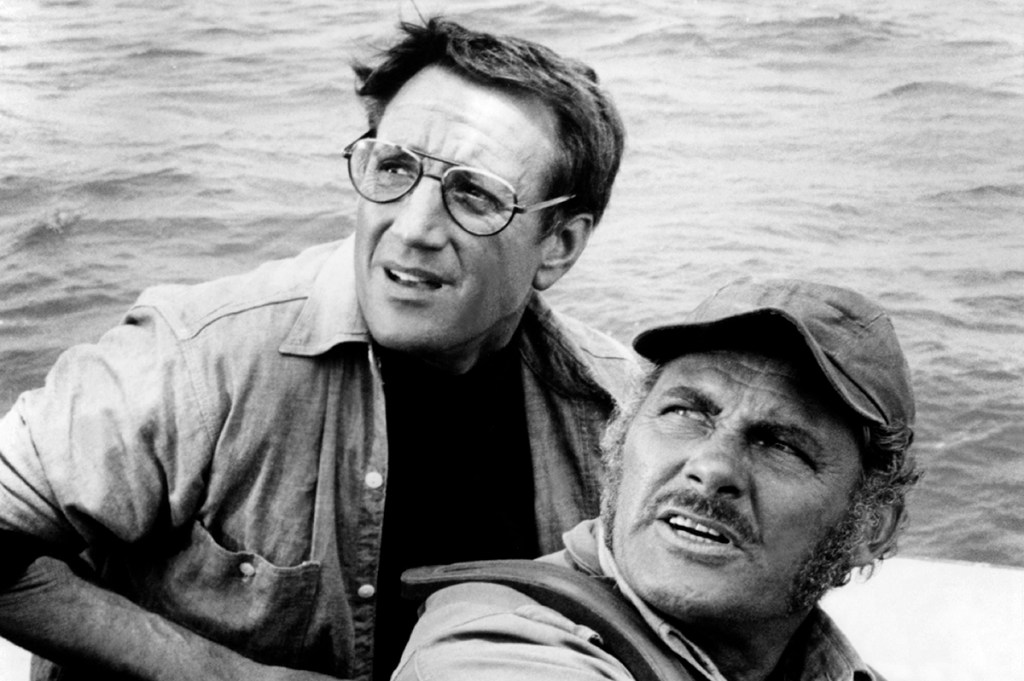

Shaw Myers has previously written the as-yet-unfilmed screenplay Jaws & Mrs. Shaw and revisits some of the same material here. In both cases, a pivotal moment comes when Robert Shaw’s mother visits the set where Jaws is being shot in 1974 off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, and thus happens to be present when her son polishes off the monologue about the shark attack on survivors of the USS Indianapolis that anticipates the gory finale of the film.

‘Most of the time, in movies, I’m about 50 times better than the part,’ Shaw observed

Shaw – who struggled with alcoholism for most of his life – had embarrassed himself with his first read-through, conducted after consuming two bottles of vodka. After sleeping it off overnight, he returned to nail the scene in one take, giving it the same sense of muted horror as Marlon Brando’s climactic speech in 1979’s Apocalypse Now. It was by far the best single performance in Jaws by a human being.

Despite his villainous roles in such hits as From Russia with Love and The Sting, Shaw never quite established himself as a movie star in the sordidly commercial sense of the term. Perhaps he had too much of the night about him for conventional heroic leads. Nor was he a martyr to false modesty. “Most of the time, in movies, I’m about 50 times better than the part,” he observed. He was not wrong. The man of real talent who longs to be acclaimed for something else is a recurring and often quite endearing figure in the arts, and Shaw always thought of himself as a writer who sometimes felt obliged to play dress-up in order to pay the bills. His chief claim to literary fame rests on his 1967 novel The Man in the Glass Booth. Essentially a rewriting of the tale of Adolf Eichmann, it poses intriguing questions about the nature of guilt – were the Nazis “just obeying orders?” – and of identity, since it turns out the titular character may not be a war criminal after all but a Jewish Holocaust victim. Shaw was justifiably proud of his novel, if less so of the ensuing movie. Disapproving of the screenplay, he had his name removed from the credits.

Shaw always thought of himself as a writer who sometimes felt obliged to play dress-up to pay the bills

Fate seemed to have cut Shaw out for a role in which he walked on the dark side of life. He led a nomadic and often lonely childhood in Britain, which took him from Cornwall in the south of England to Scotland’s Orkney Islands. His father, a doctor, committed suicide when Robert was 12. The younger Shaw went on to study at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and made his film debut with a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it part in 1951’s The Lavender Hill Mob.

Several subsequent collaborations with Harold Pinter brought him critical acclaim but little in the way of material rewards. Shaw went on to have four daughters by his first wife, then married the actress Mary Ure, who died in 1975 from an overdose of alcohol and drugs. He once told an interviewer that he was tortured by guilt and frequently woke up in the middle of the night “burning with pain and humiliation at some of the work I’ve done in films.”

Shaw eventually settled in Ireland. He was driving near his home there with his third wife and their infant son when he suddenly felt ill, stopped the car, got out and died on the roadside from a heart attack at the age of 51.

Shaw Myers outlines his uncles’ story with lesser-known information and anecdotes. His uncle’s career on the London stage got off to a poor start when he played Hamlet’s Rosencrantz wearing what he took to be a sinister eye-patch – it struck the audience as comical and there were waves of laughter. He and his fellow cast members were convinced that Jaws would be a critical and commercial disaster. Back in his local pub, Paddy’s Bar at Toormakeady, Shaw was known to re-enact his big Indianapolis speech for the customers at the bar, provided they first passed the hat round for him. The book also includes some nicely recreated repartee involving Shaw and his fellow thespians, including this exchange with Alec Guinness:

“Are you a member of the Shaw family?”

“Of course,” Robert said.

“I mean George Bernard Shaw’s family.”

“Oh. No, I am afraid not.”

“I only ask because I got my start in theatre when John Gielgud thought I was part of the Guinness brewing family. He thought I might provide some financing for his play. The man was quite disappointed to learn my mother was a whore and my father one of her clients.”

Not all of Shaw Myers’s dialogue is quite as sharp as that, and there are one or two historical errors. The ship carrying Lord Kitchener to his death in 1916 did not go down with all hands, but left a dozen survivors. London, though grievously affected, was not “nearly wiped out” by the Blitz, and the Marshall Plan was first enacted in 1948, not 1945. The author is also guilty of the occasional non sequitur. “Robert Shaw was an unusual man in many ways,” Shaw Myers writes. “He loved nothing more than talking sports, yet he moved easily in the theater world.” Shaw’s friend Harold Pinter, a serious cricket buff, is only one of several that come to mind in bridging that gap. But these are quibbles. Shaw Myers writes in a generally compelling, fluent style, and with as much humor as the essential tragedy of Robert Shaw’s life permits.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 27, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply