Did Shakespeare win the war? He was certainly Churchill’s greatest literary ally in 1940 when he sent the English language into battle. In fact it comes as a surprise to realize — at a fascinating exhibition in Washington D.C.’s magnificent Folger library — just how much Churchill saw England and its history through the eyes of Shakespeare. For a period in 1940 he became the lion-hearted Henry V — albeit Henry V with a cigar and dressed in a velvet onesie.

Shakespeare and the theatre runs through Churchill’s life. He bought a Webb’s toy cut-out theatre as a little boy. He studied hard for (but twice just missed getting) the Shakespeare Prize at Harrow. Churchill’s first book, written when he was 23, when he was an embedded correspondent fighting the Afghan tribesmen, kicks off with a quotation from the play King John and has an opening chapter ‘The Theatre of War’. He wrote, ‘most men aspire to be good actors in the play. There are a few who are so perfect they do not seem to be actors at all.’

Churchill was one of those few, I’d say. The man, the part and the props were indivisible. His 1940 speeches were his crowning performance, one that carefully hid the reality. It was rumored that what Churchill actually said, when recording his famous speech, was: ‘We will fight on the beaches, we will fight in the streets…we’ll throw bottles at the bastards; it’s about all we’ve got left!’

He was presumably encouraged in his love of Shakespeare by Jennie, his theatre-mad mother, who in 1911 organized a grand Shakespearean fancy dress ball at the Albert Hall — a thousand guests minced about to lute music in a vast indoor Italianate garden designed by Lutyens — to raise funds toward the founding of a National Theatre. Fittingly her granddaughter, Mary Soames, would become a much valued chair of the Royal National Theatre board in 1989.

When the second world war came, Churchill, in full warlord mode, adopted an intensely emotional style of speech-making, one that was Shakespearean without being cod-Shakespeare. He even had his speeches typed out as if they were in verse. The young Battle of Britain pilots he called the Few, an echo of the Saint Crispin’s Day speech in Henry V: ‘We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.’ This was a favorite throughout the war. Laurence Olivier delivered Henry’s speech on the radio to boost morale and Churchill found it so inspiring that he asked him to produce the play as a film in 1944. Shakespeare casts back then were littered with combatants. Fluellen, for example, was played by Esmond Knight, an actor who had been blinded by a shot from the Bismarck.

Churchill worked and worked at his speeches. ‘Short words are the best and old words when they are short are the best of all,’ he reckoned. One word he used often was ‘island,’ good for activating the nation’s tear ducts. Back then, every school child would have known John of Gaunt’s ‘This sceptr’d isle’ speech in Richard II. (Today it’s probably banned for being non-inclusive.) It appealed to the blitzed British probably even more than to Elizabethan theatergoers who had much less to worry about. Jacques’ Seven Ages of Man speech in As You Like It also gave Churchill a handy metaphor for everyone playing their part in the war effort.

Churchill’s weird emphases, scary growls, and deliberate mispronunciations — eg. ‘Naarzis’ (just to piss them off) — still sound thrilling on record. Innate in him was that capacity Shakespearean actors used to call ‘rhetorical command’. By contrast, Hitler was a hammy, arm-flapping rant merchant. It is thought that he had coaching from an unfunny music hall actor called Weiss-Ferdl. Hitler may have been good live; but he gave up public speaking as the war progressed because he knew he was a one-trick pony.

Being such a potent weapon, Shakespeare was also deployed by the Germans. The literary Dr Goebbels always thought the Bard was tops (‘better than Schiller!’) and he was the only ‘enemy’ playwright not to be banned in 1939. Members of Hitler Youth suffered ghastly sounding ‘Shakespeare weeks’. The ‘Unser Shakespeare’ (Our Shakespeare) movement in Germany became, under the Nazis, an attempt to get Shakespeare to wear a swastika armband.

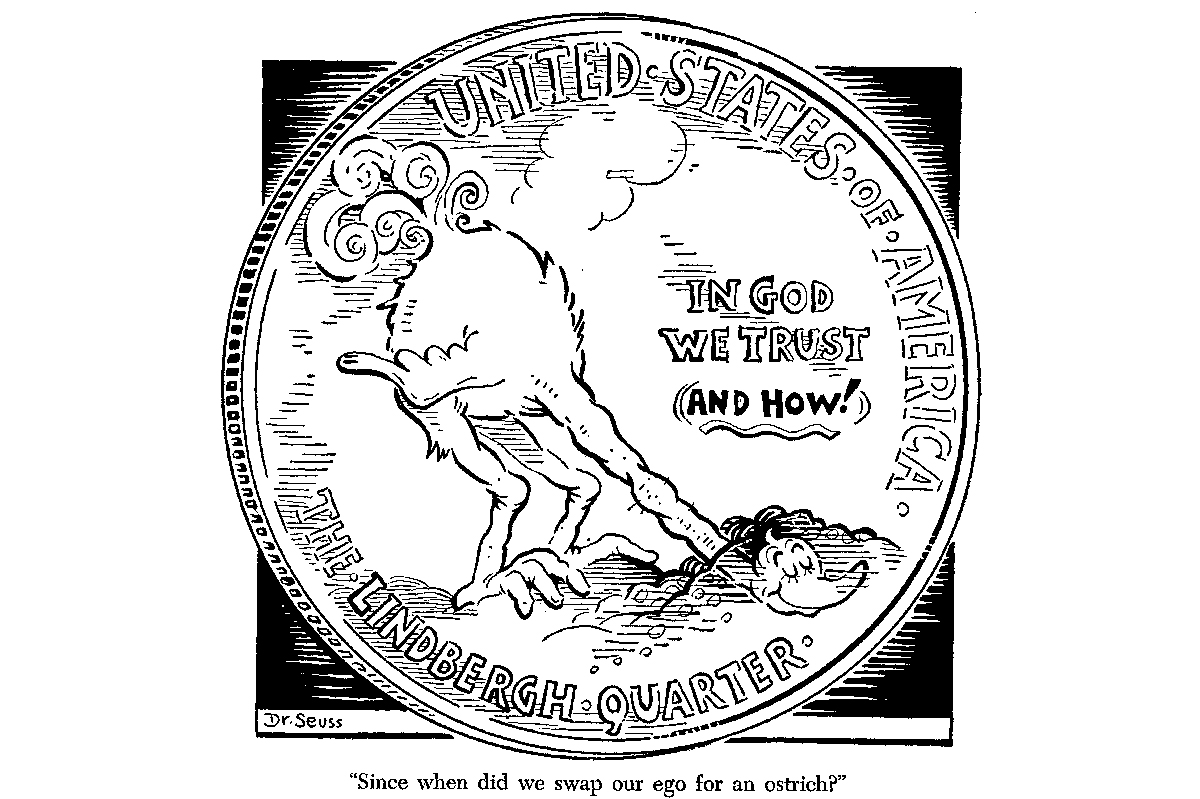

In 1939, the German weekly Simplicissimus ran a drawing of Churchill as baby-faced Falstaff, completely smashed, slumped in a chair and suffering from the whirlies. The supposedly unflattering comparison didn’t work. Like Falstaff, Churchill may have been sustained by ‘an intolerable deal of sack’ — or whisky. But no-one ever saw him actually drunk and anyway I am sure the British public was rather amused by their prime minister’s determined unfamiliarity with tap water. Punch magazine returned fire with a drawing of Hitler as the mad King Lear, raving in his jackboots beneath an August moon.

Churchill must have learned a lot as a politician by watching Shakespeare on stage. Did he get the idea of the Home Guard from the recruitment scene of the Gloucestershire bumpkins in Henry IV Part Two? Of the thousand books on Churchill is there one that tells us what exactly he saw and when?

His most well-known trip to the theatre was as an old man, to see Richard Burton’s Hamlet. ‘My lord Hamlet, may I use your lavatory?’ was his famous post-show greeting to the star in his dressing room. For the actor, the evening was a horror as the old man audibly spoke the lines just before Burton got to them.

Churchill’s molten speeches were weapons of war, intended to steady the nation’s nerve and put fire in its belly. Churchill gets all the credit. But the self-effacing man from Stratford also played his part in Hitler’s downfall.

Churchill’s Shakespeare is at the Folger Library, 201 E Capitol St SE, Washington D.C. until January 6.