The Farnsworth Museum of Art, subject to New England winters up in Rockland, Maine, and consequently confined to a shorter calendar than most museums, made one of the bolder institutional decisions in recent memory: devoting part of its precious summer schedule to showing prints about the Holocaust. Moreover, these are the sublime and horrifying woodcuts of Leonard Baskin (1922-2000), executed in the last years of the artist’s life, which he spent contemplating the ravenous appetite that Death has for the Jews.

Baskin was not to everyone’s taste, and the feeling was mutual. The critic Hilton Kramer called him a “macabre sentimentalist,” and that was only to denigrate the other artist he was reviewing at the time. Baskin, in turn, disdained photorealism and minimalist abstraction (“Both are unwilling to say anything about the nature of reality,” he said) and hated Pop Art (“the inedible raised to the unspeakable”).

Out of sync with the broader run of American visual art from his early days, he started Gehenna Press, named after the Levantine valley of fiery sacrifice: the closest concept that Jews have to hell. He made prints, befriended poets, published books and supplemented his significant though not particularly remunerative professional recognition with teaching appointments in central Massachusetts. “People like me, who care about printing, constitute the tiniest lunatic fringe in the nation,” he conceded. Blessed not only with a draughtsman’s hand but also a poet’s tongue, he accepted exile in the borderlands between fine art and illustration as the price of being himself.

Though cherished by printmakers, book artists, and art-attentive philosemites, Baskin’s work has sparked only scarce curatorial interest since his death in 2000. Books by the artist have either become unattainable collectors’ items or remainders; books about him, nearly nonexistent. The show at the Farnsworth, marking the centennial of his birth, is one of a dozen museum exhibitions dedicated to the artist in the last ten years, all of which have taken place in less-prominent art destinations like Rockland. While Baskin is not utterly neglected, Leonard Baskin: I Hold the Cracked Mirror Up to Man is nevertheless an unusual and welcome devotion of attention to him.

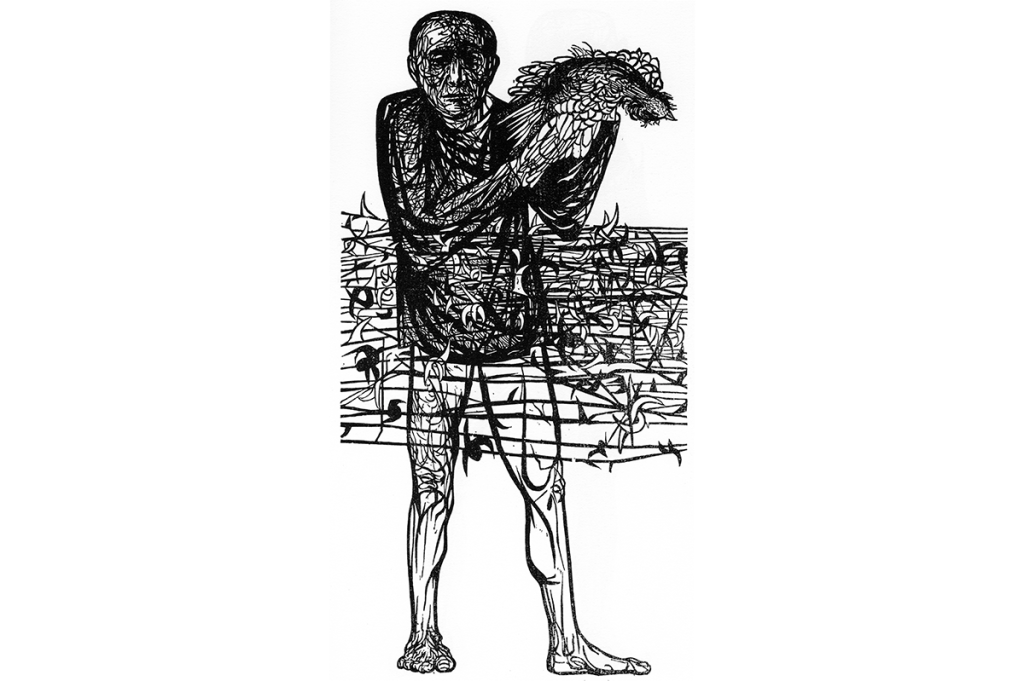

Displayed therein is “Man of Peace” from 1952. Here a beleaguered figure, exhausted and deprived of the dignity of pants, holds up a dead bird, presumably a dove wrecked by man’s insatiable warmongering. Barbed wire, hooked and exaggerated in cruelty, runs in front of his body, maybe through it. It is a cri de coeur of an artist who hated war, displaying a vehemence and visual eloquence seldom seen today.

“It took me fifty years to deal with the Holocaust at all,” Baskin recalled. He was perhaps unique among Jewish artists in America in that he was born early enough to learn of the Shoah as it happened but late enough to outlive its impossibility as a subject. Baskin found a balance between allegory and specific reference that eluded even powerful artists such as Hyman Bloom and Ben Shahn. The enormity of the Holocaust was too great, and so could only be focused through a lens of potential nuclear annihilation that wasn’t a feature of public consciousness until the US-Soviet arms race was underway. The blasted musculature of “Hydrogen Man” (1954) shows Baskin coming to grips with the implications of the Bomb.

Death for Baskin is not a wasted skeleton, but a bald brute, corpulent with his countless victims. He had long appeared in Baskin’s work, such as the bronze sculpture “Glutted Death with Wings” (1981) and the woodcut “Tyrannus” (1982). In 1998 he acquired new resolution and monstrosity in a series of woodcuts from that year, each titled with the acerbic Yiddish that appears in the backgrounds. Death stands proud in “We Lie Here Dead and His Godly Name Grows Greater and Holier.” He acquires a skull and sits menacingly in “Well Death, Have You Devoured Enough of Our Children.” He transforms into a zaftig hell-mother in “At Least Death Loves the Jews,” printed with irony on a pink ground.

Baskin noted in the 1990s that “vast vested interests” — banking, industry, museums, and all else — had steamrolled the avant-garde. When the 2000s came, artists were largely sucked into the institutional machinery that generates global atrocities in the first place. Today’s artists, even the activist-artists, lack the moral compass and the moral gravity to proclaim through their art an unambiguous, humanistic, ideology-free, Jew-loving condemnation of political violence. I say so as a challenge to them. “In this garden I dwell, and in limning the horror, the degradation and the filth, I hold the cracked mirror up to man,” Baskin wrote. “In this landscape we dwell, and with these images we must live.” Do you? Can you?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.