“Who knew the Greeks had such bad taste?” This comment was overheard at the preview for Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color, a head-turning exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This slight wasn’t targeted at the current denizens of Greece, but, rather, their ancestors of yore. You remember the type: chiton-clad Athenians — let’s not forget the ladies in their peploi! — sauntering through the agora, pondering the nature of reality or, perhaps, the role of hoi polloi within a democratic society. They’re the folks whose aesthetic sensibilities were found wanting, at least to one denizen of twenty-first-century museum culture.

What most of us know about life in antiquity is, I dare say, as broadly conceived as the above description. What most of us know about art from antiquity has been gleaned from trips to specific sites or cultural institutions here and abroad. Donatello and Michelangelo, Renaissance men who looked upon the arts of Greece and Rome as models of emulation, are, in significant part, responsible for codifying our notions about the nature and import of antique sculpture.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the pioneering eighteenth-century art historian, pressed the point: “The only way for us to become great, yes, inimitable, if it is possible, is the imitation of the Greeks.” No one seems to read Winckelmann nowadays except for the stray academic eager to score points by pegging the glories of Western art as harbingers of any and all social ills including, most indelibly, “seas of lily white, spectacled and tweed-wearing people” (as University of Iowa classicist Sarah Bond puts it).

Chroma is blessedly free of such casuistry. The Met likely took a good hard look at its bread and butter — which would be, among much else, the stunning suite of galleries devoted to Greek and Roman art — and concluded that historical and artistic fact make for better box office than tendentious sermonizing. Or, maybe, the curators were just doing their job — you know, safeguarding the legacy of world art for the pleasure of gallerygoers.

Certainly, the efforts of Vinzenz Brinkmann, head of the Department of Antiquity at the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung in Frankfurt, working in tandem with his wife Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, bear serious consideration. For over forty years, they’ve been knee-deep in the study of polychromy — that is to say, the application of paint on three-dimensional objects. The art world is filled with people who hate art but make it their business anyway. Vinzenz and Ulrike? They love their patch of multi-colored turf. Their eagerness is palpable.

It’s long been known, if not to the lay public then to anyone with more than a casual interest in the arts, that classical effigies were originally overlaid with color. Paint, being a less durable medium than marble or bronze, is incapable of withstanding the elements, let alone wear and tear over thousands of years. Historical accounts testify as to how colorful sculptures, having been unearthed through excavation, quickly lost their pigment after being exposed to sunlight and oxygen. The notion that (pace Winckelmann) “the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is” — and, yes, you can see how extremists might exploit such a statement — has been a convention difficult to overcome. Faced with the preternatural beauty of the “Venus de Milo” as it is currently seen at the Louvre, the typical museum-goer can be forgiven for thinking that, yes, this is enough.

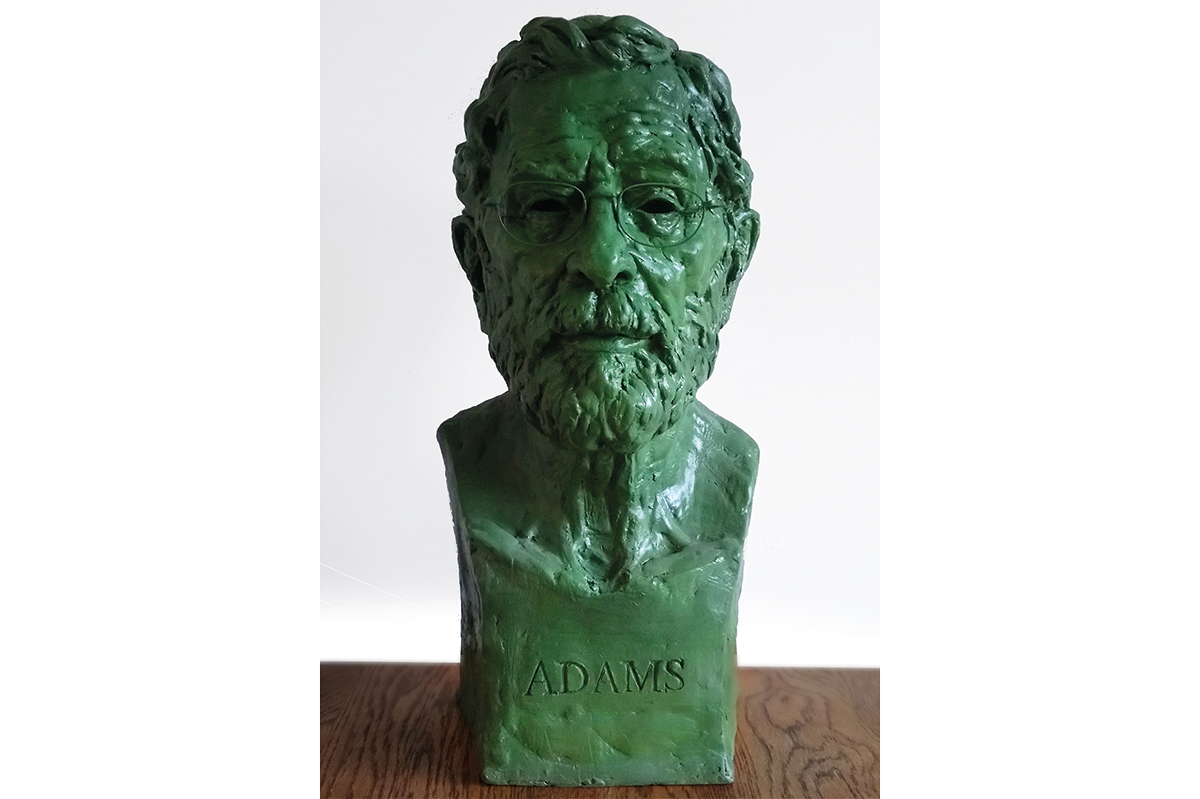

The Met show includes fourteen reconstructions of classical sculptures overseen and created by the Brinkmanns and their team. Utilizing a variety of approaches, featuring connoisseurship no less than high-tech gadgetry, they’ve managed to divine traces of color from, among other works, “Boxer at Rest,” a world-class masterwork at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, and a longstanding staple at the Met, a marble sphinx dated c. 530 BC. Most of the copies employ traditional materials — plaster and bronze, primarily. The Brinkmanns subsequently overlaid pigments and colors that were particular to the time and region. Rather than exhibit these colorized versions in a separate gallery, the curators have integrated them within the museum’s collection as a means of prompting contrast and comparison.

How do the replicas stand up to the monochrome standbys? A wall label would have us believe that “with the absence of color, ancient sculpture loses its original animation and full range of meaning.” But curatorial selling points don’t necessarily coincide with aesthetic experience. For all the dutiful research the Brinkmanns have done, their reconstructions are — well, they’re awful. I mean, really awful. Even allowing the necessary wriggle room for stylistic conjecture, there’s reason to doubt the taste of everyone involved in this venture. Blame centuries of conditioning for such an appraisal, and you wouldn’t be altogether wrong. But when the best of these pieces look like Conan the Barbarian after spending too much time in a tanning bed, and the worst like rejects from a Fisher-Price outlet store, you know things are ass-over-teakettle wrong.

A supporter of colorization might point to how the famed portrait bust of Nefertiti hasn’t suffered because of its polychromy. Scholars can readily point to numerous examples of the genre that prove the viability of the medium. (The Spanish are especially strong in polychromy.) But, really, how does “The Nefertiti Bust” stack up against “Boxer at Rest” as a work of sculpture? Color garnishes the former, bringing a degree of specificity to the bust’s streamlined — let’s not call it “generic” — dimensionality.

In contrast, the burnished patina overlaid on “Boxer at Rest” obscures the attention that’s been invested in its making. Material integrity, anatomical nuance, specificity of contour and the sterling embodiment of tragodía are diminished by somebody’s overwrought notion of mimesis. Other colorized facsimiles at the Met are considerably gaudier, what with their glassy eyes, faint attempts at painterly illusion, and color palette seemingly poached from a package of Necco Wafers. A conspiratorial soul might wonder if the point of Chroma is to wheedle a feel-good correspondence between, say, the “Nike of Samothrace” or the “Jockey of Artemision” with kitsch-mongers like Jeff Koons, Charles Ray and Takashi Murakami — between an era of high artistic achievement and our own age of bewildered expectations.

Old-school aesthetes may have misread the purity of classical sculpture, but who’s to say new school conservationists aren’t overcompensating for a culture in which overstimulation is the lingua franca? Chroma is probably best considered a lone pit stop on humankind’s eternal journey to bedevil its own finest impulses. In the meantime, let’s give it up for Mother Nature and Father Time, both of whom worked collaboratively to fine-tune our greatest achievements by ridding them of their excesses.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.