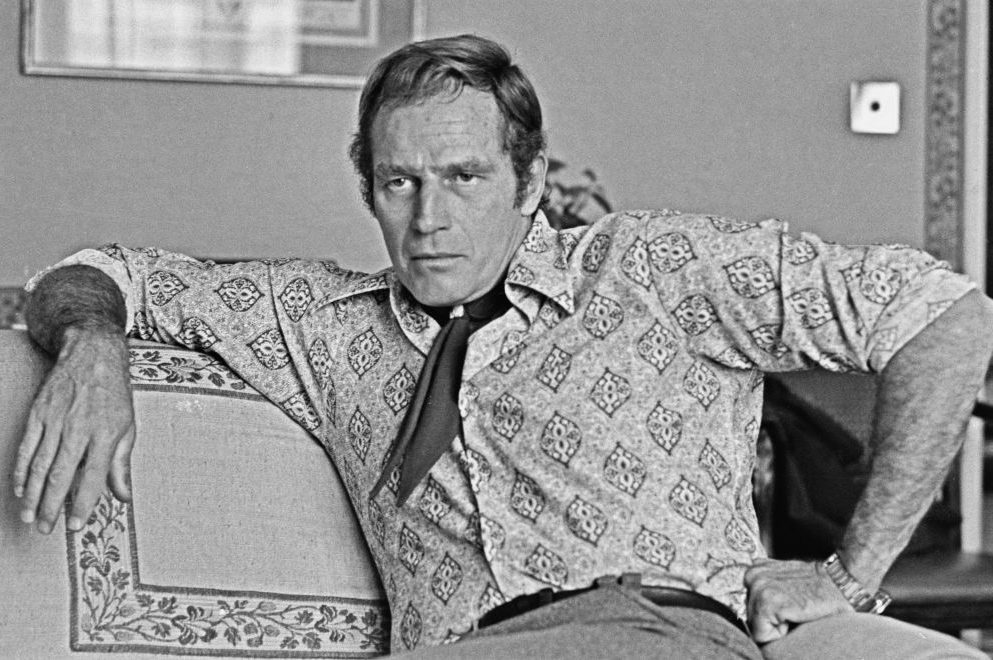

“The grand picture of life lies in the little moments,” the Indian author Abhijit Naskar reminds us in his incongruously long poem “Visvavictor.” In that same spirit, I always like to remember Charlton Heston, who would have turned 100 on October 4, not for his larger-than-life Oscar-winning roles, but the fleeting cameo he played in that underrated social satire of American suburbia in the 1990s, Wayne’s World 2.

Heston is on screen for all of thirty seconds, and dare I say it he steals the show. Near the end of the movie, Wayne — Mike Myers — in a scene that winks towards The Graduate, pulls up at a gas station to get directions to the church where his sometime-girlfriend Cassandra is to be married, and finds himself suffering through a protracted monologue from the attendant there.

Breaking the fourth wall, an exasperated Myers turns to the camera and asks, “Do we have to put up with this? I know it’s a small part, but I think we can do better than this.” On cue, the ham actor is hustled off and replaced by Heston, who begins the same monologue from the top, speaking in that inimitable voice that always sounded as if he took it out and let it marinate in a cask of port in between film roles. In precisely fifty-seven words, he gives the required directions, reminiscing as he does so about “a girl I knew who lived on Gordon Street… a long time ago when I was a young man.” There’s an absolute precision of effect to the scene; it’s funny and wistful at the same time, and Wayne leaves again with what may be an actual tear in his eye. You should watch it to see one of the finest screen actors of his generation (that would be Heston, not Myers) at the peak of his form, while as an added bonus the skillfully-played ham he replaces is one Al Hansen, who in real life happens to be Keith Richards’s brother-in-law. Small world, Wayne’s.

For many years, Heston was widely regarded as a figure of peculiarly American ruggedness, a sort of celluloid male equivalent to the Statue of Liberty, who paradoxically enjoyed playing roles both from biblical antiquity and the sci-fi future. He made at least four movies almost everyone has seen — The Ten Commandments, Touch of Evil, Ben-Hur and Planet of the Apes — but wasn’t afraid to do “ordinary” roles as well: witness his performance as an illiterate cowboy in 1968’s Will Penny, which Heston himself regarded as the best film he’d been in.

There are certain actors whose last screen performance is very like their first. Having learned their trade, mastered it for once and all, they practice it with little variation to the very end. Heston wasn’t like that. He could do it all. If there was a throughline to the eighty-odd roles he tackled over the course of fifty years, it lay in his exuding strong inner values and, perhaps more particularly for foreign audiences, in symbolizing the ideal American: a gruff, capable frontiersman who’s determined to do what’s right, even if it defies popular will. He was invariably the one to turn to in a crisis, just as the otherwise doomed 747 passengers do in the curiously-named Airport ’75, which was actually released in 1974. As even Pauline Kael, not a critic naturally drawn to the sort of old-fashioned, male authority embodied by Heston, gushed:

He’s a god-like hero, built for strength. He represents American power — and he has the profile of an eagle.

Was Heston, who died in 2008, also the kind of stereotypical, gun-toting, knuckle-dragging, right-wing nut ruthlessly depicted by Michael Moore in 2002’s Bowling for Columbine? Not entirely. Heston had a long history of libertarianism, and his belief in the individual and nonconformity was reflected in many of his best roles, not least as the scourge of police corruption he played in Touch of Evil. In real life, Heston walked alongside Martin Luther King in the early Sixties, calling King a “twentieth-century Moses,” and quietly funded scores of groups and individuals because he thought them worthy of his help regardless of their politics. By all accounts, the alcoholic director Sam Peckinpah behaved like a particularly dissolute version of Hunter S. Thompson on the set of 1965’s western Major Dundee, driving his cast to the brink of psychosis until the bosses at MGM simply announced they were closing the whole thing down. Heston not only gave up his fee to keep the project alive, but also supported Peckinpah financially until his death at the age of fifty-nine in 1984, long after mainstream Hollywood, with its way of appearing compassionate while exposing itself as the opposite over and over again, had washed its hands of the director.

It’s also worth remembering that Heston supported the uber-liberal Adlai Stevenson for the White House in 1956, vocally opposed what he saw as the political witch-hunt led by Joe McCarthy, campaigned for JFK, deemed Richard Nixon “as crooked as a corkscrew” and criticized US involvement in Vietnam, even while he went out to entertain the GIs there. To him, there was nothing inconsistent or illogical about his late-life turn to the right. Heston felt that he was still battling for American values, except that now he was standing up for the sorely oppressed middle-class against the spread of political correctness. We can only imagine him in full wrath-of-God mode raging against the manmade disasters and pervasive lunacy of more recent times.

Just a thought in closing, but might Heston, with his long-held skepticism about big government, his distaste for committing American troops to fight overseas, and his aversion to loudmouth, race-grifting politicians of every stripe actually have been ahead of his time? As Matthew Walther recently argued in these pages, most of these were at one time considered classic liberal positions until the “woke” elites reversed course and started lecturing us about the noble souls at the likes of the FBI and CIA, or how our democracy apparently came so close to cracking under the strain of being attacked by a guy wearing a Viking hat and speedos. Again just idly speculating, but what might our republic have been like in the 1990s had Heston followed his old friend Ronald Reagan and stood for the presidency of the US, as opposed to merely that of the NRA, as I’m reliably told he considered doing before instead riding off into the Hollywood sunset in roles like Wayne’s World 2, or similarly stealing the show as the Player King in Kenneth Branagh’s otherwise lackluster 1996 film version of Hamlet?

We’ll never know, but at least Heston got to deliver one of his greatest ever lines when in 1998 he told a cheering crowd of NRA supporters: “President Clinton, America didn’t trust you with our healthcare system. America doesn’t trust you with our twenty-one-year-old daughters. And we sure, Lord, don’t trust you with our guns.” Heston’s whole tenure at the NRA is an intriguing and illustrative story in itself, full of memorable scenes and oratorical flourishes like that. But somehow I can’t see it being filmed.