On one blissful, cloudless day during the summer holidays of 1972, Charles Spencer, who had just turned eight, surveyed the scene in his mother’s garden in Sussex. He’d spent the morning cycling and swimming, and a barbecue was being prepared. He remembers thinking: “This is too good to last.” And he was right. A date he was dreading, September 12, arrived. His father drove him the 100 miles from his house on the Sandringham estate in Norfolk to Maidwell Hall, the boarding prep school in Northamptonshire where Spencer would be a student for the next five years.

We all remember that end-of-summer dread: the savage haircut, the putting on of itchy school uniform after months in cotton. Spencer evokes this brilliantly in his unputdownable memoir A Very Private School. For him, though, and for each of the new boys in the dormitory, the contrast between their summer vacation and their new conditions was shockingly and terrifyingly stark.

Wrenched from the gentleness and love of home, they found themselves in an icy institution, “patrolled and controlled by a headmaster intent on inflicting pain on the boys in his care.” A word Spencer uses often in this book is “danger.” Maidwell Hall was a place of constant danger, where the boys spent every waking hour in vigilance and fear.

Spencer’s horrific, graphic account of his years in this abusive hellhole made me hate quite a few of the repulsive adults there. First on the list is the senior matron, Mrs. Ford, known as “Granny Ford.” “Charles has never spent a night away from home before,” his father confided to her on the day of arrival, “and I was wondering — only if it’s not too much bother, Mrs. Ford — if perhaps somebody kind from among the older boys might keep an eye on him till he finds his feet.” Granny Ford selected for this role a thickset bully, aged twelve, called Miles Corbet. The moment Spencer’s father had driven away, Corbet turned to Spencer, looked him up and down and spat: “You’re on your own.”

This set the tone for the way things were done at Maidwell. When Spencer started vomiting into his chamber pot every night, in what he now realizes was a desperate bid for warmth and sympathy, Granny Ford just crossly told him to wash it out. The one occasion on which she did take notice of the potful of vomit was Princess Anne’s wedding, when the boys were allowed the day off. “Well, Spencer,” she said, “if you’re so very unwell, you really must rest.” And she sent him to his dormitory for the duration. That was typical of her nastiness.

The next three people to hate are Jack Porch (the headmaster); the Hon. Henry Cornwallis Maude (third assistant headmaster); and Thomas Goffe (history master).

Maidwell Hall was a place of constant danger, where the boys spent every waking hour in vigilance and fear

Porch was addicted to caning the bare buttocks of pre-pubescent boys. When one pupil looked round mid-caning and saw the bulge in the headmaster’s cavalry twill pants, Porch barked: “How dare you turn round? Look to the front!” The school “never had a victimless day,” Spencer writes. “The staff knew that if they wanted [Porch’s] favor, they needed to present him with miscreants.” Someone should have spoken out, but none of them did: they were either “allies, enablers or mutes.”

Among Porch’s many despicable traits were his smarmy niceness to parents and his writing of witty school reports, which made the parents think he was rather marvelous and provided cover for his dark habits. He disclosed more than he intended in a letter to the parents of a boy called William Say: “He is a dear little boy.” Porch regularly summoned this “dear little boy” to his study to ask him: “What have you done wrong this week?” The boy, who was always particularly careful to stay out of trouble, felt compelled to invent a few misdemeanors. “Well, that’s very disappointing,” Porch would say, spanking his bare buttocks, his hand lingering for a fondle.

So that was the man in charge of this rotten institution. Meanwhile, Maude, also charming to parents, knocked a boy unconscious at his desk and insisted that pupils enter the school’s lake “via the human slide” — his own naked body. Goffe, “a seething human cauldron,” had a loathing for children of noble birth. He would taunt homesick ten-year-olds with unsettling questions such as: “Which option would you choose? Either you could die, or your life could be spared but your mothers and fathers would have to die instead. Go on, which would you choose?”

And then into this abyss of lovelessness came a young assistant matron, known (like other female staff at the school) as “Please,” who seemed delightful and brought midnight snacks and jollity to the dormitory. But she, too, turned out to be a predator. She prowled the dorm in the middle of the night, stopping at the bed of her chosen still-awake boy, who was far too young to be French-kissed, and induced him to put his hands into her underpants. Of course, the boys fancied themselves in love. When she threatened to leave, Spencer cut his arms to ward off this terrible possibility.

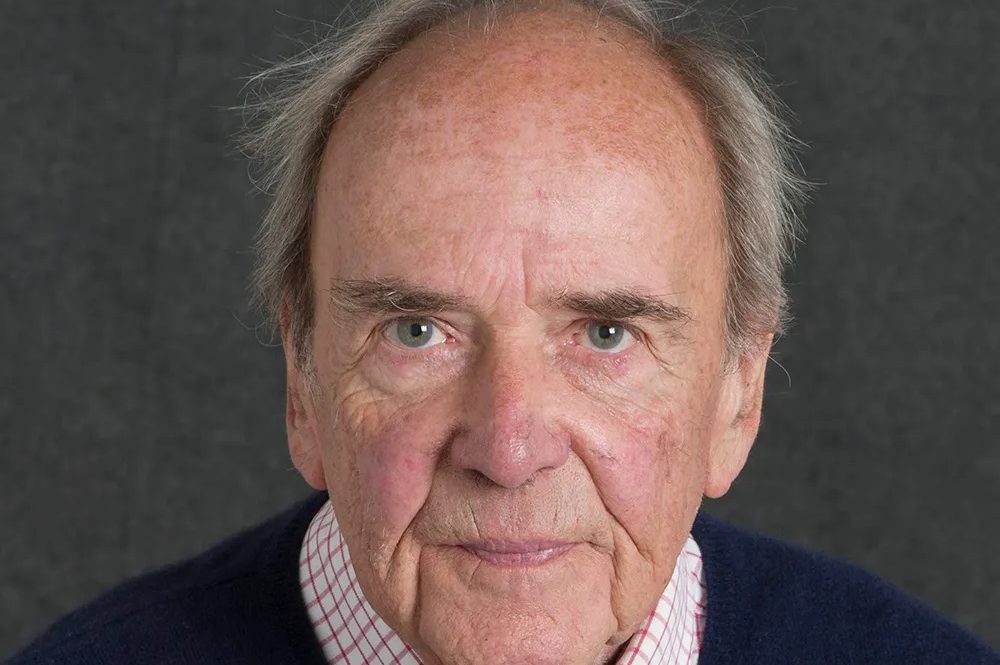

Of the batch of photographs depicting the smiling, balding, pot-bellied villains, often on sports days, a pastel drawing of Spencer, done “soon after Please had come into my life and turned it on its head,” is the most heartrending, depicting a beautiful, sad, lost boy. “A part of me died at that school,” he writes.

Recently he has confronted the older generation, trying to make them face up to why they sent their sons to such a place. Among the usual “it was the done thing, but I must say, I did cry after saying goodbye to him” responses from 1970s mothers, we hear one father saying of Porch: “But Jack did write such jolly amusing reports.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply