“All the Things You Are” is an essential jazz standard, but in 1960 the bassist Charles Mingus gave it an update: “All the Things You Could Be by Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother.” It doesn’t take a psychoanalyst to peek under the hood of this composition. Like many Mingus tunes, the loose adaptation is fairly bipolar, picking up and dropping off in fits and starts, alternating between vacuum-tight swinging sections and meandering, tempo-less squabbles between members of the four-piece band.

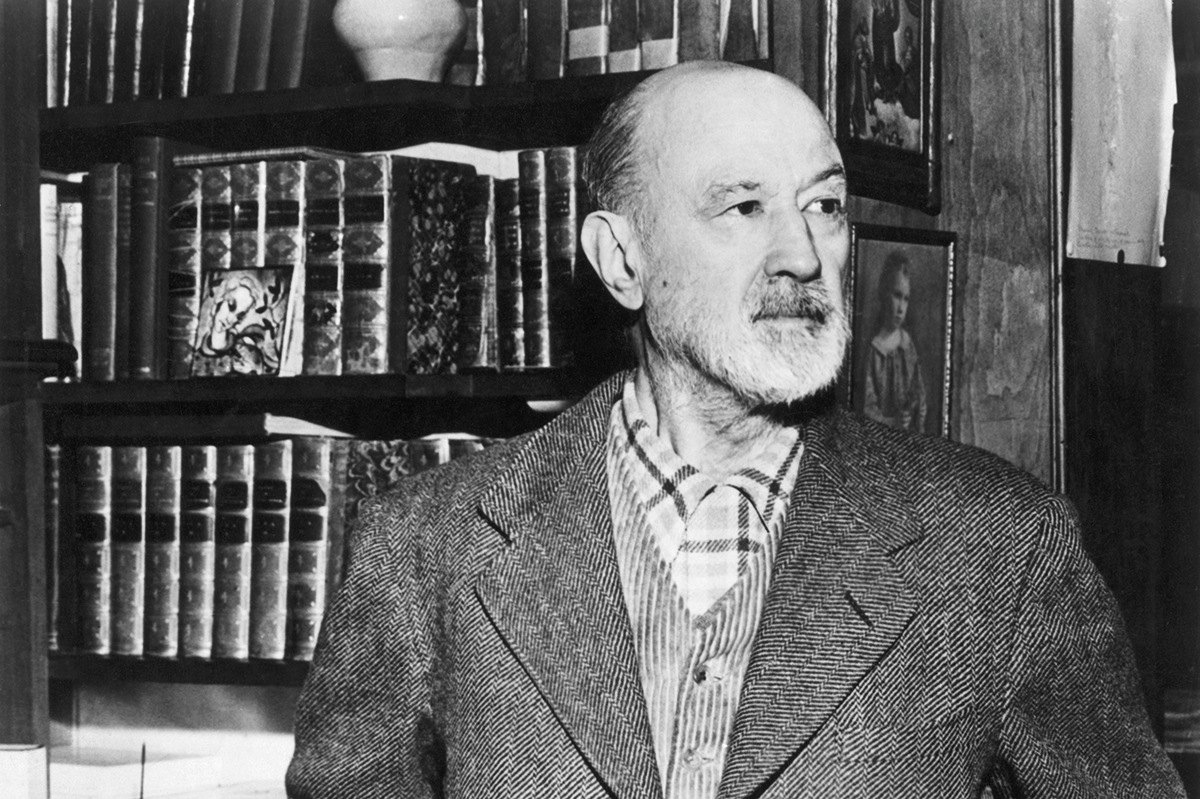

Mingus isn’t for the faint of heart, but on the centenary of his birth it’s worth confronting his life’s work, which surely places him among America’s most important composers. Born in Nogales, Arizona, on April 22, 1922, he grew up in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles and began playing music early on. He was a prodigy, and by his mid-twenties had played under, among others, Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington, whose own expansive compositions were among his most lasting influences.

In the 1950s he moved to New York and fell in with bebop, playing with the likes of Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Bud Powell, aligning himself with their high-art aspirations and intellectual fireworks. Within this tradition, Mingus found his own voice. As a bassist, he was a virtuoso for sure, yet technical take-off was never the point. At its best, his playing was firmly planted in the dirt of real feeling and experience.

Mingus soon led a group of his own. His revolving-door enterprise came to be known as the “Jazz Workshop,” its emphasis on spontaneous composition and freewheeling performance. Nevertheless, as a bandleader he was notoriously demanding. Getting the fundamentals right was an ethical matter, and this bassiste maudit could become physically combative with those deemed insufficiently prepared.

The pressure chamber pumped out real diamonds. Albums like Pithecanthropus Erectus (1956) and The Clown (1957) anticipated the free improvisation, modal frameworks and other post-bop innovations that others would earn credit for in ensuing years.

With an ambiguous racial identity that included African, German, Chinese and Native American heritage, Mingus outraged against the boundaries of essentialist thinking. He was fiercely integrationist and didn’t shy from infusing his compositions with explicit political content. In 1959, the same year that Miles put out Kind of Blue, Mingus released Ah Um, proving that jazz could still be hot, not cool. On it is the tour de force “Fables of Faubus,” which assails the Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, who two years earlier had called in the National Guard to block the Little Rock Nine from going to class: “Boo! Ku Klux Klan (with your Jim Crow plan)”; “Two, four, six, eight/ They brainwash and teach you hate.”

Columbia Records wouldn’t allow these lyrics onto the album — too profane, apparently — but the instrumental “Faubus” pierces nonetheless, its lurching theme a devastating pantomime of the governor’s bumbling barbarity. Few have more convincingly demonstrated that the language of formal music is a more-than-adequate vehicle for political expression, and Mingus never doubted its real-world impact: “Stravinsky is nice, but Bach is how buildings got taller. It’s how we got to the moon, through Bach, through that kind of mind that made that music up.”

Yet these were no mere protest tunes. Anger and bile were there, but also love and beauty. Like the man himself, the music was emotionally eclectic and enormously varied: “In my music, I’m trying to play the truth of what I am. The reason it’s difficult is because I’m changing all the time.” His compositions are like obstacle courses, straining the attention span of the listener with their clashing themes and abruptly shifting time signatures and tempos. “Mingus music” was always going in multiple directions at once — up and down, left and right.

Forward and backward, too. Mingus had little patience for the progressivist posturing of the so-called “avant-garde.” Thus, while Ornette Coleman was predicting The Shape of Jazz to Come in 1959 like a day trader picks stocks, Mingus kept the tradition in his pocket. His workshop was endlessly inventive yet also looked back on the decentered improvisations of New Orleans Dixieland. Fragments of flamenco, pinches of prayer meeting, scraps of Strauss — all this and more spilled out of his overflowing compositions.

In the late 1960s, financial difficulties caused Mingus essentially to give up music for several years. Though he reemerged in the next decade, in 1977 Mingus was diagnosed with ALS and died just two years later, at the age of fifty-six. One wonders what he might have been able to accomplish with more time. He had dreamed of creating spontaneous symphonies at the hours-long scale, but his most ambitious composition, the gloriously circuitous “Epitaph,” wouldn’t see the light until a decade after his death. “I wrote it for my tombstone,” he once predicted. Magic Mingus, right again.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.