John Dollard (1900-80), trained in sociology at the University of Chicago and in psychoanalysis at the Berlin Institute, brought the sensibility of a novelist to a five-month study in Indianola, Mississippi, which he wrote up as Caste and Class in a Southern Town (1937). Dollard went south, but what he found applied in the other direction: The ‘caste line is drawn in the North as effectively, if not as formally, as in the South,’ which meant ‘We are still deliberately or unwittingly profiting by, defending, concealing or ignoring the caste system.’

Caste, Dollard argued, had far-reaching implications: ‘Our social system has come under world inspection and is literally being looked at by several billion people or their competent agents.’ William Faulkner would say or imply as much not only in essays and speeches in the 1950s, but in his wartime Hollywood screenplays, like the unproduced Battle Cry, in which he named an African American character America, a wounded warrior carried to safety by a white Southern good-old-boy-soldier.

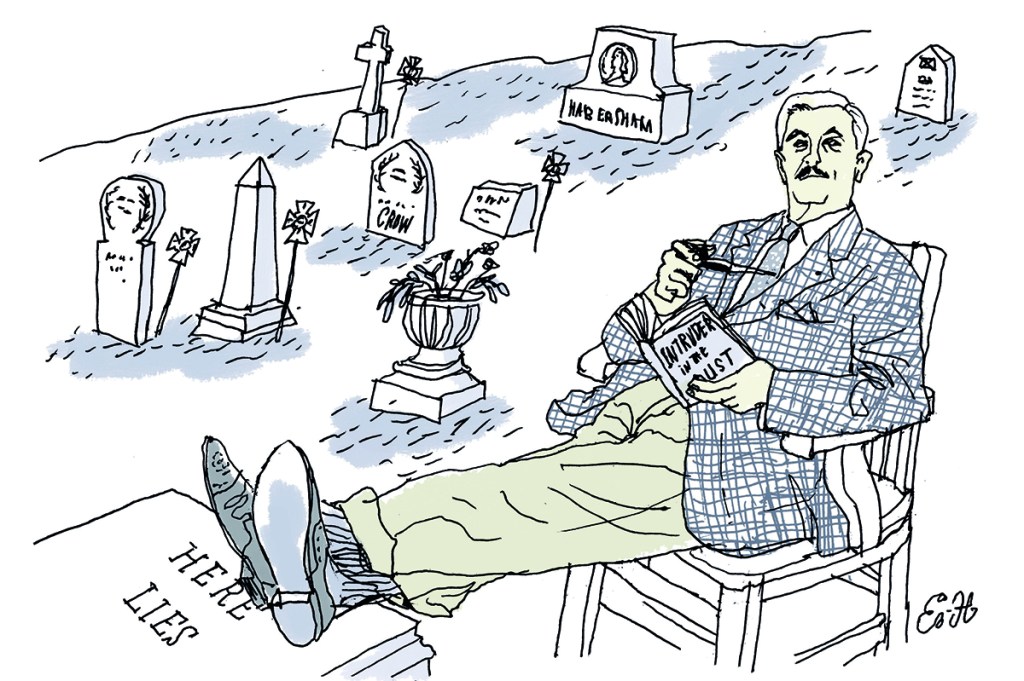

It is unlikely that Dollard had anything new to convey to a reader like William Faulkner, if, in fact, Faulkner ever read the book in Oxford, which is about 110 miles from Indianola. But Intruder in the Dust (1948) nonetheless reads like a remarkable anatomy of the caste system, not only as Dollard discovered it, but as Isabel Wilkerson, acknowledging Dollard’s influence, has tracked on a global canvas in her recent Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent:

‘Throughout human history, three caste systems have stood out. The tragically accelerated, chilling, and officially vanquished caste system of Nazi Germany. The lingering, millennia-long caste system of India. And the shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid in the United States.’

Wilkerson’s phrasing — ‘shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid’ — leads right into the opening pages of Intruder in the Dust. Jefferson, Mississippi ‘had known since the night before that Lucas [Beauchamp] had killed a white man’. Of course, they know no such thing. Lucas, black and notoriously independent, flouts his place at the bottom of the race pyramid, and a lynching will be the white retribution for a crime and will also serve to put down all others of his subordinate race. As Dollard observed of lynchings, what mattered was not punishing the right man but punishing the ‘Negro caste… through one of its representatives.’

Across from the jail is a 16-year-old white boy, Chick Mallison, ‘trying to look occupied or at least innocent’. He is part of what is ‘unspoken’. He is not supposed to acknowledge what is about to happen any more than the novelist was ever to admit what he knew concerning Nelse Patton’s lynching in 1908, just a few blocks from 12-year-old Billy Faulkner’s home. Only in fiction did Faulkner dare to reveal what he knew about the code of caste.

Chick knows Lucas Beauchamp ‘as well that is as any white person knew him.’ Behind that statement is a regime of dominion over African Americans that Dollard found paradoxical. His white informants often touted how well they knew ‘their Negroes’ while at almost the same time complaining that Negroes were mysterious and hard to read. In this respect, Lucas Beauchamp, who keeps his own counsel, is the instigator of the sort of white uneasiness, Dollard surmised, that hid a fear of revolt — if the enforcement of caste was not unremitting. With any let-up at all, the individuality that Lucas personifies might well overwhelm caste boundaries.

Four years earlier, Chick, then 12, had fallen through the ice in a creek during a hunting expedition on the property of white landowner Roth Edmonds, near Lucas’s home. Lucas had ordered the white Edmonds boy and Chick’s black companion, Aleck Sander, to get Chick out of his ice hole. Climbing an embankment Chick looks up at a man with a hat like Chick’s grandfather would have worn. The shape of caste has shifted. Lucas crowns himself, making no effort to get Chick out of the creek. It is one of those intervening moments Wilkerson writes about, when a member of the upper caste suddenly realizes what it means to be brought low. Lucas looks out of his skin as if he ‘had no pigment at all not even the white man’s lack of it, not arrogant, not even scornful: just intractable and composed’.

The white Edmonds boy addresses Beauchamp as ‘Mister Lucas’, a title no white is supposed to use for his inferior. When Dollard called his African American informants by ‘Mr’ or ‘Mrs’, he outraged the white community, who called him a ‘nigger lover’. When two boys told Faulkner he was called a ‘nigger lover’, the novelist replied that it was better than being a fascist. ‘To be a “nigger lover”,’ Dollard observed, ‘suggests the person is a traitor to his caste, and that his fondness for Negroes is headlong and impractical.’ The epithet also reflected, as Faulkner’s novel and Dollard’s study make apparent, the ‘constant and potent pressures to compel every white person to act his caste role correctly’.

Lucas Beauchamp is descended from old Carothers McCaslin’s slave, who was also old Carothers’s son, and that lineage matters, as Dollard learned when African-American informants mentioned their pride in their white blood, although Lucas deviates from the Dollard pattern by not expressing, as the sociologist’s informants did, any sense of being ‘scorned and rejected’ by their own white relations.

Lucas shows no deference to Chick, no fear, no sense of dependence on his white caste-masters. He turns his back on Chick and issues a command: ‘Come to my house.’ In effect, Lucas takes on the paternal power of the upper caste. When Chick says he will return to the Edmonds house, Lucas ignores him and says to the black boy: ‘Tote his [Chick’s] gun, Joe.’

Dollard would have recognized Lucas’s dominance as not merely an affront to the caste principle but as a blow to this white boy’s pride of place. Or to state the obverse: ‘a member of the white caste has an automatic right to demand forms of behavior from Negroes which serve to increase his own self-esteem’. When that subservient behavior was not forthcoming, Dollard saw that white image of self, of ‘being something special and valuable,’ deflated.

John Cullen, one of Faulkner’s white hunting companions who published a book, Old Times in the Faulkner Country, about his friendship with Faulkner, told his collaborator, Professor Floyd Watkins: ‘Lucas Beauchamp was more independent than he could actually get away with as a real person in Oxford.’ Indeed, John Dollard found no African American like Lucas Beauchamp, unafraid of white retaliation. Dollard concluded: ‘Every Negro in the South knows that he is under a kind of sentence of death; he does not know when his turn will come; it may never come, but it may also be at any time.’ Faulkner creates a character who could not have existed but who is absolutely necessary so that the novelist can expose what did exist and why it could not continue.

Lucas strides ahead ‘incapable of conceiving himself by a child contradicted and defied’. Chick is on Lucas’s sovereign ground, deeded to him by his white first cousin, 10 acres of land ‘set forever in the middle of the two-thousand-acre plantation like a postage stamp in the center of an envelope.’ Negro landowners, Dollard reported, were at special risk of being driven off their property and often retained it only with the support of what was called an ‘angel’, a white man who served as a protector, which is exactly what Mr Edmonds is. ‘It seems that every white family has some Negro or Negroes whom it protects,’ Dollard learned.

Lucas orders the sodden Chick to strip off and dry himself. Chick again tries to recover his caste authority, announcing that he will take his dinner at the Edmonds home. Lucas now is devoid of his racial designation: ‘The man neither protested nor acquiesced. He didn’t stir; he was not even looking at him [Chick]. He just said [referring to his wife], inflexible and calm: “She done already dished it up now.”’ After the meal, Chick attempts to give Lucas four coins. ‘What’s that for?’ Lucas asks, refusing to acknowledge he has done a service for the white boy. Chick drops the coins on the floor and orders Lucas: ‘Pick it up!’ Lucas ignores Chick and tells the Edmonds boy and Aleck Sander to pick up the money and return it to Chick, who is then dismissed: ‘Now go on and shoot your rabbit… And stay out of that creek.’

Wilkerson’s Caste dramatizes many such moments in her life and in the lives of others when the demeaning aspects of caste are exposed in an intervention of a kind that virtually no white person in Faulkner’s time could imagine. As Wilkerson notes, ‘without intervention or reprogramming, we act out the script we were handed’. Caste is installed in the ‘subconscious of every one of us’, as well as the ‘fear of losing caste’.

Lucas triumphs because he will not allow caste to work against him in the large and small ways that, as Wilkerson puts it, ‘elevate or demean, embrace or exclude.’ After his encounter with Lucas, Chick has to choose, in Wilkerson’s words: ‘We can be born to the dominant caste but choose not to dominate. We can be born to a subordinated caste but resist the box others force upon us.’ A ‘world without caste’, she proclaims, would set everyone free.

A chagrined Chick thinks: ‘Lucas had beat him.’ Chick is so desperate to assert his white privilege that he thinks: ‘If he would just be a nigger first, just for one second, one little infinitesimal second.’ This is not merely Chick’s dilemma. He expresses his community’s anxiety, since submission cannot be extorted from Lucas Beauchamp. Dollard discovered a few cases where African Americans tried to assert themselves as Lucas does and they were ‘driven out of the community or otherwise disposed of.’

When Chick tries to send a Christmas gift of a dress for Molly, Lucas’s wife, a white boy on a mule shows up with Lucas’s gift of a gallon bucket of sorghum molasses. In short, ‘what would or could set him [Chick] free was beyond not merely his reach but even his ken.’ How ironic that it is the white teenager who cannot be ‘set free’.

When Lucas arrives at the jail in the sheriff’s custody, he looks at 16-year-old Chick and issues a command: ‘You, young man. Tell your uncle I wants to see him,’ and then calmly walks into the jail. Beauchamp is not without resources. Half the time, Dollard reported, lynchings were prevented by ‘conscientious white citizens and law officers’.

Faulkner casts doubt on Lucas’s guilt. The crime occurs in Beat Four, a violent stronghold of the Gowries, a family of white supremacists. But Lucas has been apprehended with the purported murder weapon in his hand. Chick’s uncle, county attorney Gavin Stevens, supposes Lucas is performing his part in the caste pyramid: he ‘blew his top and murdered a white man’, which is what white people expect, Stevens observes.

‘Whites have raised niggers from savagery,’ John Cullen, Faulkner’s boyhood friend and adult hunting companion, told the scholar Floyd Watkins, reflecting what many Southerners of Faulkner’s generation believed and what they told John Dollard — that in certain circumstances black people would return to their primitive state. A lynching seemed to Cullen a vindication of white supremacy. Present at the lynching of Nelse Patton in 1908, Cullen said without a trace of irony about who was savage: ‘I was proud. Somebody cut his balls off. Somebody scalped him. I don’t know who done that. I was just a bystander.’

When Stevens and Chick enter the jail to visit Lucas, he is asleep, confirming Chick’s conception of caste: ‘He’s just a nigger after all for all his high nose and his stiff neck and his gold watch-chain and refusing to mean mister to anybody even when he says it. Only a nigger could kill a man, let alone shoot him in the back, and then sleep like a baby as soon as he found something flat enough to lie down on.’

This is the preposterous thinking Dollard encountered everywhere, a mindset that typed African Americans as children or primitives unaware of the consequences of their actions. It never occurs to Chick that Lucas is asleep because he has not killed a man. Stevens tells Lucas: ‘I don’t defend murderers who shoot people in the back.’ Stevens is upset because Lucas won’t call him mister. He yells at Lucas about how the Gowries are going to lynch him.

Finally, Stevens calms down enough to absorb Lucas’s story about how he has observed two white timber-mill partners, one cheating the other, hauling timber late at night, selling it and pocketing the profits. Stevens doesn’t wait to hear the rest and simply concocts what he thinks the arrogant Lucas did: tell a white man another white man is cheating him and getting knocked down by the white man cursing him and calling him a liar, which, in turn, results in Lucas shooting him in the back. Stevens advises Lucas to plead guilty and let his lawyer argue that his old age and lack of a criminal record deserves a merciful verdict — being sent to the penitentiary. Realizing the garrulous Stevens is hopeless, Lucas bids Stevens goodbye, saying ‘If you stay here you’ll talk till morning.’

Lucas needs to find another way to save himself, to stage another intervention, so he turns to Chick. Stevens departs, but Chick returns the same night to Lucas’s cell, because of the unspoken understanding between them. As he enters, he says ‘All right. What do you want me to do?’ But Chick already knows. He has to dig up Vinson Gowrie’s body to prove, as Lucas tells him, that Gowrie was not shot with Lucas’s gun. It has to be Chick, because neither the sheriff nor Stevens would countenance such a request. As another old black man once said to Chick: ‘Young folks and womens, they ain’t cluttered. They can listen.’ When Chick doubts he can get to the grave and return all in one night, the laconic Lucas replies: ‘I’ll try to wait.’

Faulkner was fond of detective stories and read them in cheap paperbacks right off the rack in Oxford’s drugstore. Mysteries make a mockery of convention and caste; the detective is often the outsider in terms of class or iconoclastic even if in the upper caste. With Intruder in the Dust, Faulkner first set out to tell a detective story, but he discovered that the very notion of pursuing clues depended on the ability to see them in a society cluttered with all that cant about black people and their willing participation in the rightness of whiteness. Characters like Lucas and Chick stand out, affronts to the casuistry of caste.

How is Chick going to dig up a body in a cemetery several miles from town? In desperation, he calls on his Uncle Gavin, who dismisses Lucas’s defense, saying any man, black or white, would say it was not his gun. Besides, how could the attorney ever convince the Gowries to dig up their dead kin to exonerate a ‘nigger’? Chick rules out his father, realizing he would get the same answer, but then hears the same thing from his black companion, Aleck Sander, who adds: ‘It’s the ones like Lucas makes trouble for everybody.’ Everybody, in short, is implicated in a caste paradigm that no one is willing to challenge. But out of friendship, Aleck Sander helps Chick saddle up a horse and tote the pick and shovel needed for the exhumation.

In yet another intervention, Miss Habersham, who happens to be in Stevens’s office when Chick barges in, follows the boys as they saddle up to save Lucas. She asks Chick about what Lucas told him. She is the oldest surviving member of the town’s founding families and is interested because of Molly, Lucas’s wife, who is the same age and a descendant of one of Doctor Habersham’s slaves. Molly and Miss Habersham have grown up ‘like sisters, like twins,’ taken care of by Molly’s mother. ‘Miss Habersham had stood up in the Negro church as godmother to Molly’s first child.’ As soon as Chick tells her that Lucas said it was not his pistol, Miss Habersham replies immediately: ‘So he didn’t do it.’ She is in a position to understand that killing a low-caste white man like Vinson Gowrie is beneath Lucas’s dignity, his caste pride.

Miss Habersham exercises the privileges of her upper-caste position, bound to make its own rules and execute its own plans when necessary, as she muses about Lucas: ‘Naturally he wouldn’t tell your uncle. He’s a Negro and your uncle’s a white man.’ She takes over, using her truck as well as Chick’s horse to tote the body from the grave to the truck. When they open the grave, Vinson Gowrie is not there. Instead they find Jake Montgomery, a ‘jackleg timber buyer’. Now Chick, Aleck Sander and Miss Habersham have to apply to Stevens and Sheriff Hampton to make yet another intervention before the Gowries get to town to lynch Lucas.

Stevens looks at Miss Habersham and ventures, ‘But if a woman, a lady, a white lady…’ The nature of caste is so ingrained that Miss Habersham understands her mission: she is to sit on the steps in front of the jail barring the lynchers who would not dare to run over her.

As a mob gathers in front of the jail, Chick realizes that all of the county has made the lynching possible:

‘It seemed to him now that he was responsible for having brought into the light and glare of day something shocking and shameful out of the whole white foundations of the county which he himself must partake of too since he too was bred of it, which otherwise might have flared and blazed merely out of Beat Four and then vanished back into its darkness or at least invisibility with the fading embers of Lucas’ crucifixion.’

Faulkner prolongs the suspense halfway through the novel when Stevens starts to talk too much in what Chick earlier calls the ‘significantless speciosity of his uncle’s voice,’ or what Dollard terms the ‘defensive ideology’ of Southerners who attack a federal government that is interfering with the high caste privilege of setting African Americans free since the North has not been able to do it. This is the same Gavin Stevens that in Light in August spouts nonsense about white and black blood.

The case against Lucas collapses as soon as the grave is opened. After some convoluted plot twists it is discovered that Crawford Gowrie, an army deserter and criminal involved in a timber deal gone wrong, has murdered two men, his brother Vinson and Jake Montgomery, who has been blackmailing Crawford. Faulkner, never good at the sheer mechanics of detective-story plotting, is more interested in Chick Mallison’s reaction to the lynch mob that rushes away from the town square when they realize Lucas Beauchamp is not their prey. Stevens tries to palliate Chick’s disgust with the mob, suggesting they ran to save their consciences: it was run or have to stand there and admit they were wrong. They are running, Stevens adds, from Crawford Gowrie, although Stevens does not explain what he means. Presumably, what troubles the mob is that the murderer is white and a fratricide, and they are ashamed.

The caste consensus collapses and then is reconstituted when Chick muses that the instant the ‘bullet struck Vinson Gowrie… Lucas was already dead… in the same instant, and theirs [the mob’s] was merely to preside at his suttee’. This is Faulkner’s notion of time: ‘It’s all now you see. Yesterday wont be over until tomorrow and tomorrow began ten thousand years ago.’ That could be said as well for the Indian conception of caste, of a widow who performs suttee, flinging herself on her husband’s funeral pyre in her devotion — sometimes coerced — to caste. Lucas is no widow, but Stevens had earlier supposed that any white man would now take Lucas ‘out and burn him, all regular and in order and themselves acting as he is convinced Lucas would wish them to act: like white folks; both of them observing implicitly the rules: the nigger acting like a nigger and the white folks acting like white folks and no real hard feelings on either side.’ In short, this is the ritualistic Southern version of suttee.

At the beginning of Caste, Wilkerson describes a 1936 photograph of Hamburg shipyard workers all facing the same direction and ‘heiling in unison,’ except for one man, August Landmesser, who folds his arms and refuses to give the Nazi salute. An Aryan and a Nazi, he fell in love with a Jew. Forbidden to marry her, he began to understand the perverted nature of Nazi ideology. Wilkerson concludes that:

‘unless people are willing to transcend their fears, endure discomfort and derision, suffer the scorn of loved ones and neighbors and co-workers and friends, fall into disfavor of perhaps everyone they know, face exclusion and even banishment, it would be numerically impossible, humanly impossible, for everyone to be that man.’

Faulkner wrote to a European friend, ‘I am doing what I can. I can see the possible time when I shall have to leave my native state, something as the Jew had to flee from Germany during Hitler.’ Faulkner’s fiction is his version of the 1936 photograph. Intruder in the Dust stands apart from both the lynchers and Southern whites like Stevens, implying that history changes slowly, but sometimes dramatically, one individual at a time.

Carl Rollyson is the author of a two-volume biography of William Faulkner. The Life of William Faulkner: The Past is Never Dead (1897-1934) and This Alarming Paradox (1935-1962) were published by the University of Virginia Press in 2020. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.