Given my affection for M*A*S*H, I can’t think why I haven’t listened to Alan Alda’s podcasts before now, besides the fact that they look quite uninviting. There is Clear+Vivid, on the power of communication, and Science: Clear+Vivid, on the power of scientific research. As someone who used to fall asleep listening to cassettes for high-school physics, I am not easily excited by protons, and was prepared to give the latter particularly short shrift. Five hours on, however, Alda is still in my ears, and I am buzzing like an electron.

Unlike many presenters, Alda, 85, doesn’t pretend not to know something just so that his interviewee will explain it to the audience, but nor does he strive to reveal how much he knows. Rather, the depth of his understanding of really quite complex science shines through his questions and his clear rephrasing of ideas put to him, sometimes obliquely, by the experts he talks to.

Most weeks, he is in conversation with someone who works at a university or in a lab or, in the case of a recent guest, Anna Ploszajski, a material scientist with an interest in craft. You can’t help but imagine their reaction when the email came through. Alan Alda wants to interview me? Even hundreds of episodes in, there is no predicting what he will ask, or where he will want to take his line of inquiry.

Ploszajski was eased in with a question about transparency: ‘How come I can see through a piece of glass when it has atoms in it?’ The answer — because the atoms in glass are not in any kind of structural order by comparison with something like metal —prompted Alda to recall that he had learned from playing theoretical physicist Richard Feynman in a drama that some photons pass through glass, while others bounce back. Since Feynman wondered how each photon knew ‘which way to go’, Alda felt justified in asking the same, which is typical of his intelligent yet self-effacing style of questioning. He is truly the perfect host.

Atlas Obscura, an American online travel magazine, offers quite a different type of science podcast. Episodes typically take the form of short dispatches on a discovery, project or building somewhere in the world. One of the publication’s so-called ‘place editors’ zones in on Allan Hills in Antarctica, dubbed ‘meteorite heaven’ by one geologist, and formerly home to ‘a small, potato-shaped rock’ believed to be the oldest Martian meteorite ever found on Earth. A reporter, meanwhile, visits a football stadium in Arizona, beneath which is a furnace producing mirrors measuring 27 feet tall for use in a telescope designed to be 10 times more powerful than the Hubble. Someone looking through it at Phoenix, she said, would be capable of seeing the detail on a dime held by someone standing in Tucson.

The only drawback to listening to this podcast is that it has you constantly reaching for your phone for pictures. Not that being inspired to research something further is ever a bad thing. Hearing of a new library in Yusuhara Town in Japan resembling ‘something out of a young-adult dystopian movie’, with a ceiling suggestive of a forest, naturally set me googling. The building, I learned, is constructed predominantly from local cedar wood, and known as the ‘library above the clouds’.

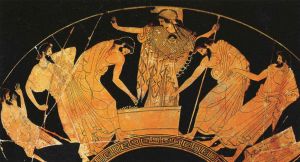

On the subject of cloud-based living, The Flock is a new ‘audio drama with songs’ told from the viewpoint of birds who plan to escape their current lives and establish a utopian Cloud Cuckoo Land in the sky. The plot clearly owes much to an ancient Greek comedy by Aristophanes, while the overall flavor is reminiscent of Cats, interwoven with elements of Hitchcock’s The Birds.

Feathered Jonny Swift opens the drama, explaining that the birds are in revolt, escaping their cages, tempted by the prospect of a new world. It transpires that many of them are driven to the forest and then skyward by environmental concerns. ‘The city was so noisy, my call was lost,’ cries one. Another, imprisoned in a pet shop, ‘called, but no one ever called back’.

The birds urge each other on in song: ‘We’ll raise our wings in flight… when the moment is just right.’ The lyrics may lack the ingenuity of T.S. Eliot — did I really hear ‘crossing’ rhyme with ‘esophagus’? — but the mix of Latin bird names and rap-like interludes is fun. This may well be the first time that a bird has insulted another bird as ‘basic’. Their plan, when they reach new heights, is to make humans’ lives more difficult or, as one bird puts it, to ‘stop them in their tracks with poo’.

Children will love this, though it isn’t immediately clear that they are the target audience. The drama is likely to leave others divided over whether it’s so quirky that it’s brilliant, or so derivative and am-dram that it isn’t.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.