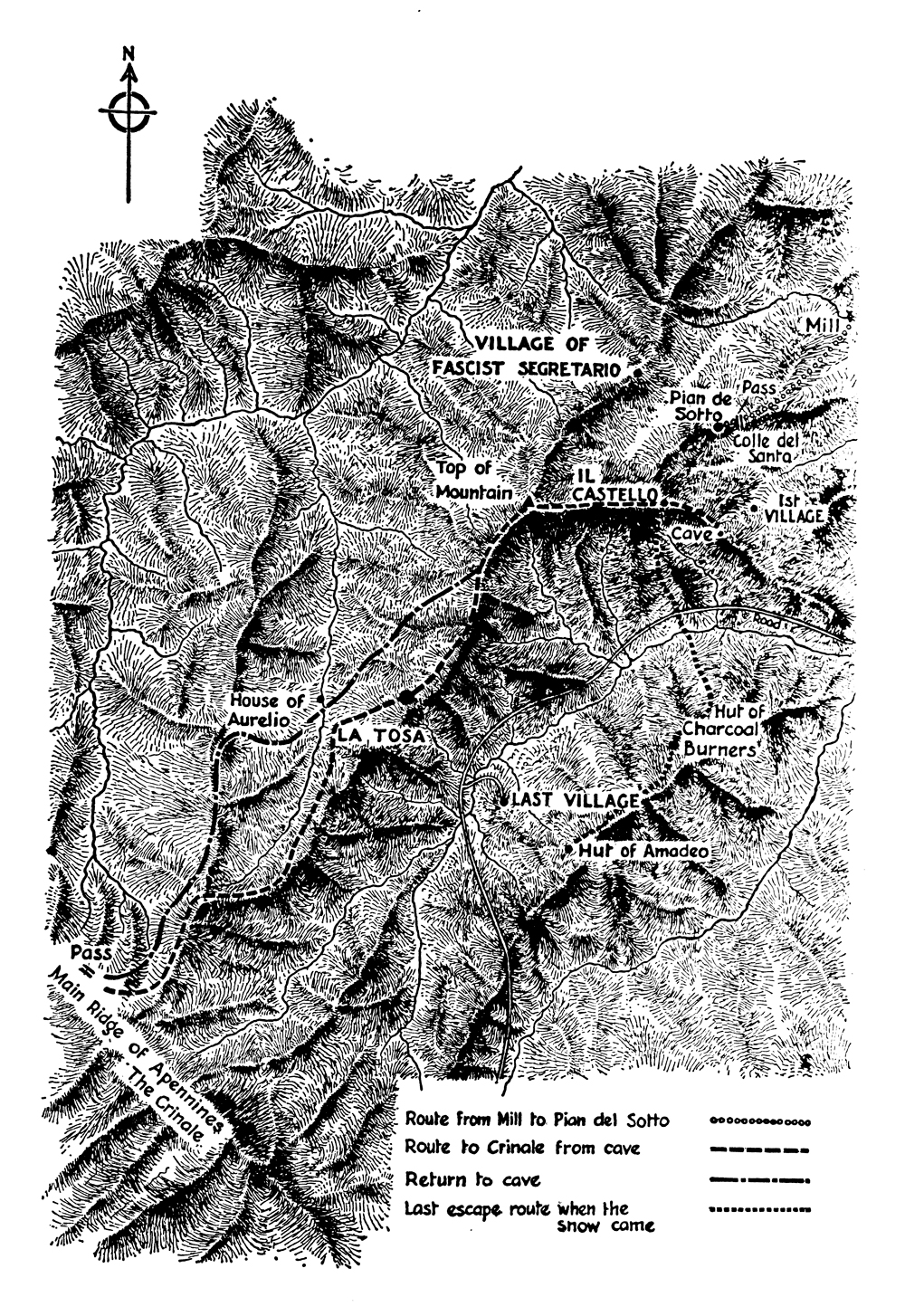

In the winter of 1943, Eric Newby, captured in 1942 on a commando raid on Sicily, escaped from an Italian prisoner of war camp. Love and War in the Apennines, his memoir of life on the run among the peasant farmers of the Apennine Mountains, is that rarest of combinations, a military classic and a love story. Patrick French’s tribute to Newby’s memoir can be read here. In this excerpt, Newby describes an unlikely encounter in a mountain pasture.

As I climbed, the trees began to thin out and at last I came to a place where there was nothing but juniper growing. Then, quite suddenly, the wood came to an end and I was out of it on what resembled a steep-sided English downland, an inclined sea of cropped grass with little islands of yews rising from it over which half a dozen hares were streaking away uphill, fanning out as they went, alarmed by what must have been a rare visitor. Here I turned left and walked along the ragged coastline of the wood towards what I hoped would be the upward continuation of the steep ridge above the village, and after about a quarter of an hour I came to it.

I was on the edge of an enormous cliff which formed the entire south face of the mountain. It must have been between four and five miles long from east to west, and it swept up to what might be the summit of the mountain, or a crest on the way to it; there was no way of knowing. It was a geological phenomenon, the result of some great convulsion. It was as if a giant who had been sleeping in the depths below had suddenly woken and raised himself on his elbows in his subterranean bed, lifting the blankets of rocks above him, crumpling them as he did so, and had then subsided again, leaving his knees up.

The sheer parts of this cliff were as I imagined the great precipices facing the Atlantic on the west coast of Ireland might be, Croaghaun, Slieve League, the Cliffs of Moher, cliffs I had read about but never seen, rather than something far inland in Italy. It fell away perhaps two thousand feet into a narrow valley through which a shallow river flowed over stones. On the right bank there were a couple of villages with red-tiled roofs, one of which had a campanile rising in the middle of it. Across the valley there was another mountain which formed the southern side of it. This mountain had a long, blunt ridge and was less high and less steep than the one on which I was standing, and it was partly covered with forest. Below the ridge of this other mountain was a little plateau with a lake on it which looked as if it was man-made, because it was too perfect a circle to be natural, and on the outer rim of it there was a small building from which an enormous red pipe descended in one single, straight swoop to a hydroelectric station in the valley below, a concrete building of the Twenties with tall windows. From the head of the valley, beyond the highest of the two villages, a road climbed to what appeared to be a sort of pass. And beyond that, what must have been a further stretch of country which, in military parlance, was ‘dead ground’, out of sight, were some peaks of the main range that I had not been able to see from the Pian del Sotto because the ridge above the village and the bulk of the mountain behind blocked the view of them.

I estimated that the highest of them were probably between five and six thousand feet, and they were linked by ridges which had lesser peaks along their length which seemed to have some sort of vegetation growing on them but as the nearest of them were between six and seven miles off, it was difficult to be sure. In one or two places thin coverts of trees reached up to them, as if they were trying to draw the forests below, of which they were the highest on the cold, north face of the range, up over the top of it and down the southern side into the sun.

I took off my rucksack and lay down in a grassy hollow at the edge of the cliff. The sun was hot and soon I took off my shirt and then my boots and socks. The air was filled with the humming of bees and the buzzing of insects and from somewhere further up the mountain there came the clanking of sheep bells, carried on a gentle breeze that was blowing from that direction. Then a single bell began to toll in the valley, and other more distant bells echoed it, but they soon ceased and I looked across to the distant peaks which previously had been so clearly delineated but were now beginning to shimmer and become indistinct in the haze that was enveloping them. And quite soon I fell asleep.

I woke to find a German soldier standing over me. At first, with the sun behind him, he was as indistinct as the peaks had become, but then he swam into focus. He was an officer and he was wearing summer battledress and a soft cap with a long narrow peak. He had a pistol but it was still in its holster on his belt and he seemed to have forgotten that he was armed because he made no effort to draw it. Across one shoulder and hanging down over one hip in a very unmilitary way he wore a large old-fashioned civilian haversack, as if he was a member of a weekend rambling club, rather than a soldier, and in one hand he held a large, professional-looking butterfly net. He was a tall, thin, pale young man of about 25 with mild eyes and he appeared as surprised to see me as I was to see him, but much less alarmed than I was, virtually immobilized, lying on my back without my boots and socks on.

‘Buon giorno,’ he said, courteously. His accent sounded rather like mine must, I thought. ‘Che bella giornata.’

At least up to now he seemed to have assumed that I was an Italian, but as soon as I opened my mouth he would know I wasn’t. Perhaps I ought to try and push him over the cliff, after all he was standing with his back to it; but I knew that I wouldn’t. It seemed awful even to think of murdering someone who had simply wished me good day and remarked on what a beautiful one it was, let alone actually doing it. If ever there was going to be an appropriate time to go on stage in the part of the mute from Genoa which I had often rehearsed but never played, this was it. I didn’t answer.

‘Da dove viene, lei?’ he asked.

I just continued to look at him. I suppose I should have been making strangled noises and pointing down my throat to emphasize my muteness, but just as I couldn’t bring myself to assail him, I couldn’t do this either. It seemed too ridiculous. But he was not to be put off. He removed his haversack, put down his butterfly net, sat down opposite me in the hollow and said: ‘Lei, non e Italiano.’

It was not a question. It was a statement of fact which did not require an answer. I decided to abandon my absurd act.

‘Si, sono Italiano.’

He looked at me, studying me carefully: my face, my clothes and my boots which, after my accent, were my biggest give-away, although they were very battered now.

‘I think that you are English,’ he said, finally, in English. ‘English, or from one of your colonies. You cannot be an English deserter; you are on the wrong side of the battle front. You do not look like a parachutist or a saboteur. You must be a prisoner-of-war. That is so, is it not?’

I said nothing.

‘Do not be afraid,’ he went on. ‘I will not tell anyone that I have met you, I have no intention of spoiling such a splendid day either for you or for myself. They are too rare. I have only this one day of free time and it was extremely difficult to organize the transport to get here. I am anxious to collect specimens, but specimens with wings. I give you my word that no one will ever hear from me that I have seen you or your companions if you have any.’

In the face of such courtesy it was useless to dissemble, and it would have been downright uncouth to do so.

‘Yes, I am English,’ I said, but it was a sacrifice to admit it. I felt as if I was pledging my freedom.

He offered me his hand. He was close enough to do so without moving. It felt strangely soft when I grasped it in my own calloused and roughened one and it looked unnaturally clean when he withdrew it.

‘Oberleutnant Frick. Education Officer. And may I have the pleasure of your name, also?’

‘Eric Newby,’ I said. ‘I’m a lieutenant in the infantry, or rather I was until I was put in the bag.’ I could see no point in telling him that I had been in the SBS, not that he was likely to have heard of it. In fact I was expressly forbidden, as all prisoners were, to give anything but my name, rank and number to the enemy.

‘Excuse me? In the bag?’

‘Until I was captured. It’s an expression.’

He laughed slightly pedantically, but it was quite a pleasant sound. I expected him to ask me when and where I had been captured and was prepared to say Sicily, 1943, rather than 1942, which would have led to all sorts of complications; but he was more interested in the expression I had used.

‘Excellent. In the bag, you say. I shall remember that. I have little opportunity now to learn colloquial English. With me it would be more appropriate to say “in the net” or “in the bottle”; but, at least no one has put you in a prison bottle, which is what I have to do with my captives.’ Although I don’t think he intended it to be, I found this rather creepy, but then I was not a butterfly hunter. His English was very good, if perhaps a little stilted. I only wished that I could speak Italian a quarter as well.

He must have noticed the look of slight distaste on my face because the next thing he said was, ‘Don’t worry, the poison is only crushed laurel leaves, a very old way, nothing modern from I. G. Farben.’

Now he began delving in his haversack and brought out two bottles wrapped in brown paper which, at first, I thought must contain the laurel with which he used to knock out his butterflies when he caught them; but, in fact, they contained beer, and he offered me one of them.

‘It is really excellent beer,’ he said. ‘Or, at least, I find it so.

Eric Newby’s Love and War in the Apennines is available in a limited and numbered cloth-bound hardback edition of 2,000 copies from Slightly Foxed.