Boxing has long been a British obsession, exported successfully to North America, but never widespread on the Continent. Mainland Europeans struggled to understand that in general there was no quarrel between contestants who assaulted each other so brutally. ‘Anything that looks like fighting,’ explained one bewildered French visitor, ‘is delicious to an Englishman.’ He might have said the same about drinking or gambling, pastimes embedded in the fabric of Georgian society to an ‘astonishing extent’. They were habits, moreover, upon which the popularity of boxing depended.

The story of Daniel Mendoza, little known except to sporting historians, is fascinating on both a personal level and more generally. The man one paper called that ‘celebrated hero of the fists’ was a ‘man for his time’, the late 18th century: a lavishly gifted boxer, as bare-knuckle fighting became vastly popular.

It was not unusual for fights, casually arranged and marketed by today’s standards, officially frowned upon if not forbidden, to be watched in rain-sodden fields by tens of thousands. ‘It is astonishing,’ reported one newspaper correspondent, ‘how numerous the crowds of people of all ranks and descriptions’ were.

What was additionally remarkable about Mendoza was that he was Jewish by birth — from a Sephardic family — and had to defy shocking levels of racial prejudice to reach the pinnacle of his sport. Wynn Wheldon calls his three encounters with Richard Humphreys ‘the greatest series of fights of the 18th century’, to be classed, he would argue, with those involving Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier.

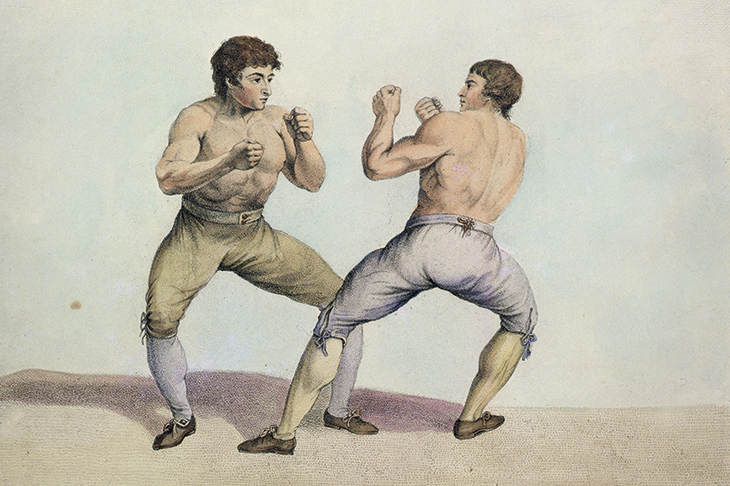

This was a time when boxing moved from what was essentially a brawl into something closer, for all its brutality, to an art form. Mendoza’s teaching, long after retirement, along with his aptly named book The Art of Boxing, ensured him a lasting influence. He was a genuine celebrity in what was ‘celebrity’s first great age’.

If a man for his time, though, he is no less clearly a man for ours. An impoverished Londoner, he faced unimaginable discrimination, ridicule and intolerance on his way to establishing himself as the effective champion of boxing in this country — a man familiarly known as the ‘little black bruiser’ or ‘the fighting Jew’. (We can’t call him a ‘heavyweight’: at under 11 stone, he wasn’t, and he fought in an age before weight categories, often against larger and heavier men.)

In many ways it is a familiar story: a rise to unheralded fame and riches and reverence, poorly dealt with and the gloomily inevitable precursor to physical decline, familial disappointment, financial incompetence and a sad demise. But it is fascinating nevertheless, and always fleshed out with the broader history of the time: American independence, industrial revolution, the French Revolution, wars between England and France and the abolition of the slave trade.

The book’s colloquial style sometimes grates. ‘It’s a “maybe”’, Wheldon writes of one unknown. ‘Somehow I think this unlikely’, he says of another. And ‘I’m fairly sure that Mendoza saw the comedy in this anecdote’. More generally, it is hard to revitalize a sporting hero without the corroboration of video footage upon which acceptance of greatness will depend.

It is harder still when the ‘rules’ governing a sport are very different to the one known today. The absence of gloves is one such difference. So too are the lack of a knock-out rule, giving any fighter much longer to recover, or indeed to fall over deliberately if in need of a breather, as well as the great length of bouts. Fights regularly enter their ‘34th round’.

I was interested in the book. Would I recommend it? It’s a points decision, not a knock-out.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.