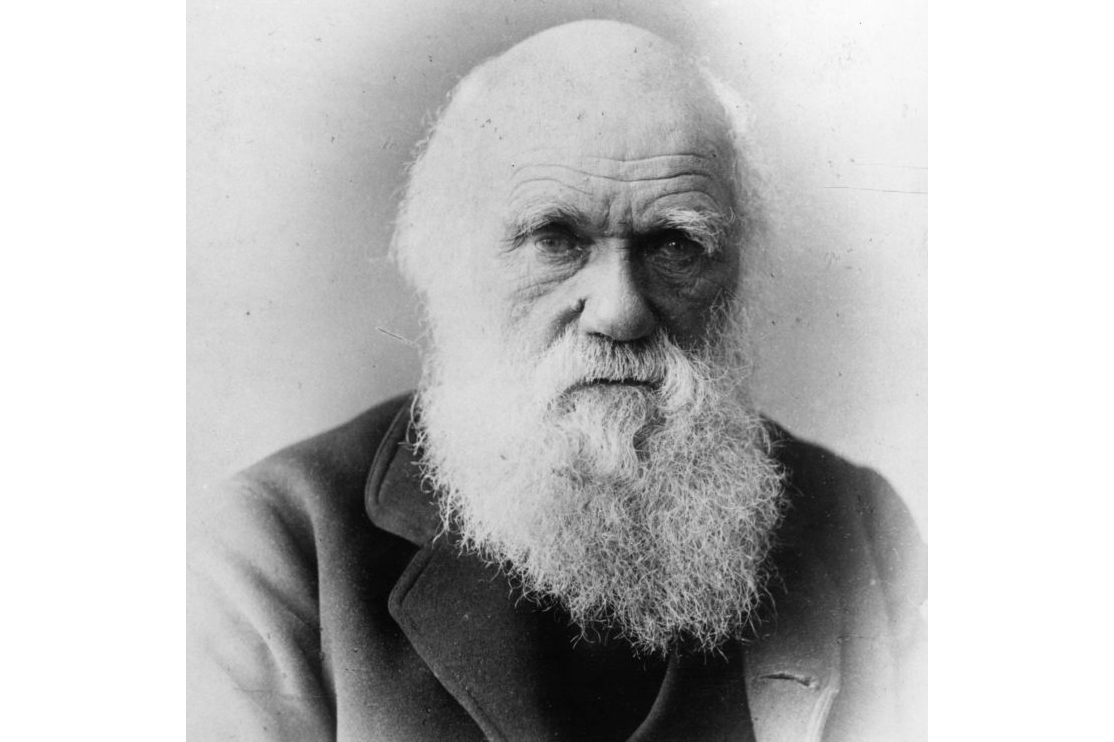

Ever since enlivenment of the primordial blob, before thoughts were first verbalised, all nature has always been motivated by a dynamic ambition to improve, to grow stronger, more agile, inventive and fertile. The successful continuously grow more successful; the failures disappear. This selective, upward process has been defined as evolution.

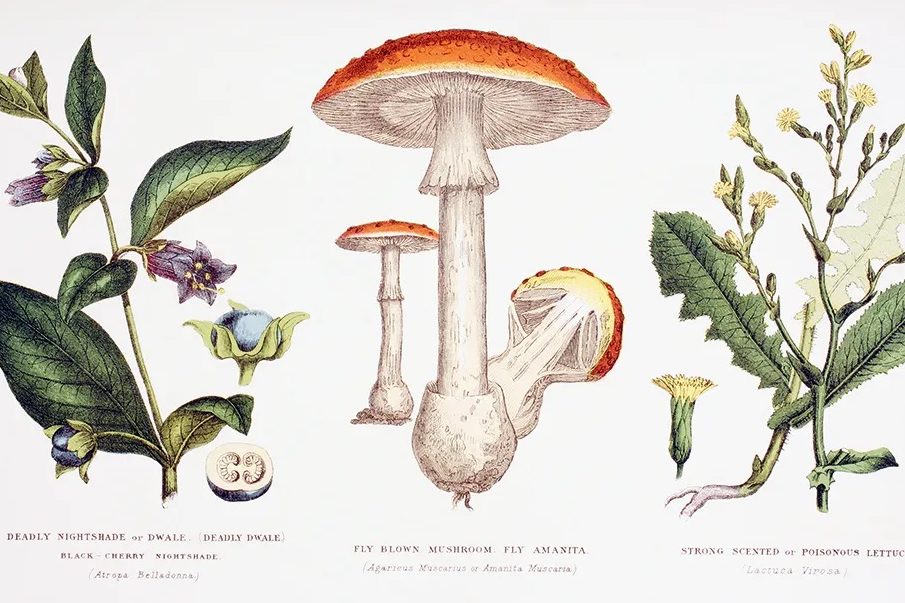

Dr Adam Rutherford, a British geneticist, half Guyanese, a contributor to The Atheist’s Guide to Christmas and a former editor of Nature, is well able to explicate scientific complexities, including the origin and development of man. He writes with intellectual authority and also, as a popular lecturer and broadcaster, expresses himself in a clear and persuasive manner with natural charm. The point of his new book, quite simply, is that ‘Humans are animals’. The genetic code of DNA is universal, he points out, shared with ‘bacteria and bonobos, orchids, oaks, bed bugs, barnacles, triceratops, Tyrannosaurus rex, eagles, egrets, yeast, slime moulds and ceps’. ‘All life on Earth is related by common ancestry, and that includes us.’

Man is closely related to the gorilla, chimpanzee and orang-utan, but is obviously more advanced than any of them. As Hamlet declared, we are ‘the paragon of animals!’ Darwin too praised man’s ‘god-like intellect’, while confirming the ‘indelible stamp of his lowly origin’. ‘If you tidied up a Homo sapiens woman or man from 20,000 years ago, gave them a haircut and dressed them in 21st-century clothes,’ Rutherford claims, ‘they would not look out of place in any city in the world today.’

He makes this more or less complimentary assessment though most Europeans carry a small but significant percentage of DNA that was acquired from Neanderthals, inherited when our species outlived them about 40,000 years ago. Their name is used now as a term of abuse, as if Neanderthals were the epitome of uncouthness — shambling morons whose knuckles scraped the ground. In fact, ‘they showed clear signs of modern behaviour: they made jewellery, employed complex hunting techniques, used tools, had a control of fire and made abstract art’. Rutherford does much to enhance the images of our ancestors and cousins.

Humans attained superiority largely through technological progress.

The truth is that almost all animals do not use technology at all. Tool-making animals make up less than one per cent of species. But where the adoption of external objects to extend a creature’s abilities is limited in absolute numbers, there is a diversity that ranges across taxa: tool use has been documented in nine classes of animals — sea urchins, insects, spiders, crabs, snails, octopuses, fish, birds and mammals.

While some less ingenious animals typically use stones to crack marine shells and sticks to prise honey out of hives and marrow from bones, we invented gunpowder, anaesthetics, the internal combustion engine and the internet. ‘We’ve taken technology to levels of sophistication indistinguishable from magic.’

Several chapters confirm his revelation that evolutionary biologists love thinking about sex, ‘not only to try to understand how to decouple sex in all its myriad forms from reproduction, but how the sex lives of animals are also a carnival of delights’. In surveying this most alluring subject, Rutherford offers many nuggets of esoteric observation, such as that ‘the majority of sexual encounters in giraffes involve two males necking… This is where the sex lives of giraffes gets interesting.’

Luke O’Neill, the author of Humanology, is a professor of biochemistry at Trinity College Dublin, who was awarded a fellowship of the Royal Society for original research in the human immune system. At the same time he won a national reputation in Ireland as a regular guest on the Pat Kenny radio talk show. There, according to his publisher, the distinguished professor answers difficult scientific questions ‘in his uniquely hilarious manner’. In his book, which is entertainingly illustrated, mostly in colour, O’Neill intersperses his text with frivolous asides. The excellent, educational treatise is presented by a master who evidently believes his readers would have been unable to bear the burden of unrelieved seriousness.

‘For some people,’ he writes, the human species ‘began with two hippies and a talking snake.’ So much for the Garden of Eden and that forbidden knowledge. In a chapter called ‘The God Invention’, he comments that, ultimately, ‘it is science that has the best chance of helping us understand more about where we came from, who we are and maybe even where we’re going’. He sketches the vastness of the universe, notes that there are billions of planets of ‘the right size and distance from their suns to allow for the chemistry of life to occur’, and concludes: ‘It is now almost certain that we are not alone’ — and that our extinction, sooner or later, is inevitable.

In the meantime, we should have fun. O’Neill expounds at length on the therapeutic value of laughter. He divulges the product of ‘a scientific attempt to find the world’s funniest joke’. Its creation is credited to Spike Milligan, and it is really quite amusing in his neurotic way.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.