A man bites a woman’s breast with the aim of drawing blood, before taking a cigarette lighter to her stomach. The woman’s lack of arousal at this cruelty causes the man to enquire angrily why she lied when she told him she was “a masochist.” A young secretary is spanked by her boss for mistakes in her typing, before he masturbates over her naked behind. In a conversation between two young adulterous lovers, a woman casually admits to “flirting… like wild” with a man after she discovered he had “broke his girlfriend’s jaw.”

These snapshots of masochism, warped desire and sexual depravity made Mary Gaitskill famous when her short story collection Bad Behavior first appeared in 1988. “All of the stories here have something to do with what used to be called sexual perversion,” wrote the New York Times critic George Garrett, as he praised her formal brilliance and “utterly unsentimental… ruthlessly objective and sympathetic” nature. This collection — along with two more of her books — is now published by Penguin Modern Classics: quite the accolade for a writer who is not yet out of her sixties.

If Gaitskill was received in 1988 as a writer who dealt with the murky worlds of “sadomasochistic fun and games,” little has changed as a result of her later writings. In 1991, Bad Behavior was followed by Gaitskill’s first novel Two Girls, Fat and Thin — a story rich in disturbing plotlines involving sadomasochistic behavior. Because They Wanted To, her 1997 short story collection, tells of runaway children selling flowers outside brothels, semi-consensual sexual encounters, and depictions of rape and humiliation. Her next novel Veronica, published in 2005, weaves decades-old memories of sexual assault and betrayal with contemporary casualties of the AIDS crisis. And Don’t Cry (2009) — Gaitskill’s most recent short story collection — takes a wry look at sexual difficulties and complications when, in “Mirrorball,” a man accidentally takes a part of a woman’s soul during the course of a one-night stand.

Gaitskill’s own life adds an air of mystery and gritty reality to the murky worlds she writes about. After running away from home at the age of sixteen, she spent time selling flowers on the street to prostitutes and their customers. Her life story echoes that of many of her female characters who are runaways or, as in the case of both women in Two Girls, Fat and Thin, victims of child sex abuse — something she wrote about in her 2021 essay on Lolita.

It is this combination of a dramatic background and writing about subjects which might appeal to oversexed devotees of the Marquis de Sade that has seen Gaitskill left in the margins of literary fame. Despite being awarded an Arts and Letters Award in 2018 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2002, Gaitskill has not reached the level of appreciation and adoration afforded to her fellow female essayists and novelists like Joan Didion or Zadie Smith. She does not appear on the New York Times’s list of “the best works of American fiction of the last twenty-five years” and, when she does feature in similar articles, it is only her novel Veronica which is mentioned.

But in our post-#MeToo world, are stories about brutal sex, unusual desire and the darker sides of lust just too outré? It would seem so. When Gaitskill’s most recent work — The Devil’s Treasure: A Book of Stories and Dreams — was published in 2021, it only received one review in the mainstream American press. With its more fashionable focus on sexual harassment in the workplace, This is Pleasure received rather more attention back in 2019.

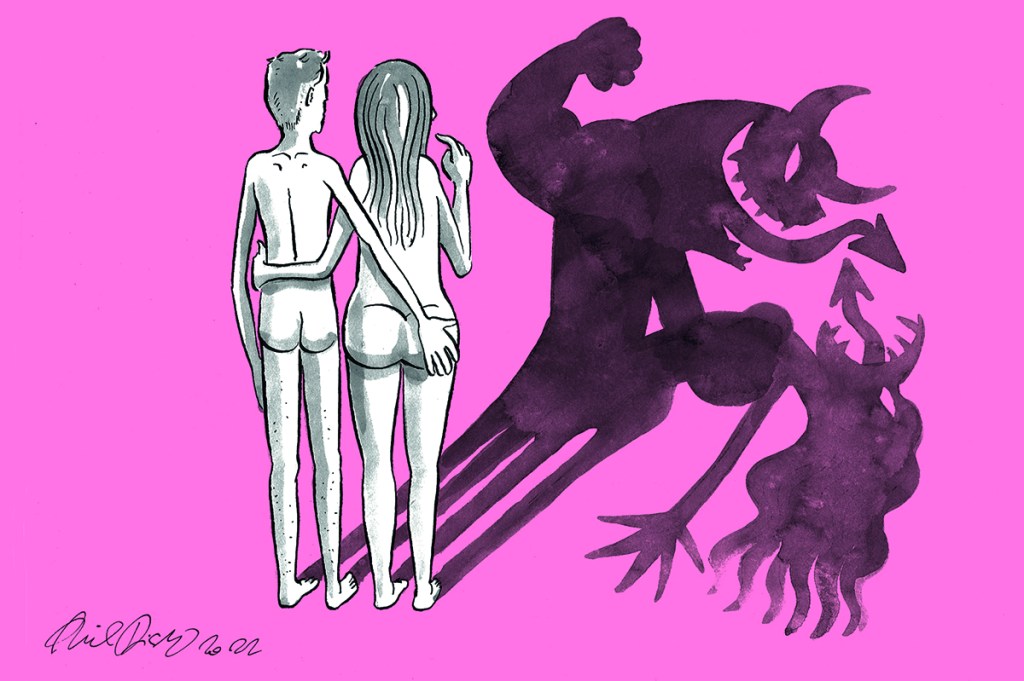

But to argue that Gaitskill has slipped off the literary map because of her subjects does a disservice to her work. Gaitskill does not describe BDSM, sex work and violence for the purposes of pornography or erotic excitement, but nor does she depict it solely to horrify her readers.

At the end of Two Girls, Fat and Thin comes a typical example. The book is a comment on Ayn Rand’s “objectivism.” The young journalist who had been exploring the devotees of “definitism” falls foul of her boyfriend’s violent sexual interests.

Justine Shade lay naked on her bed, her hands and feet tied to its corners, her head raised, her wild mascara-smeared eyes staring at me with utter incomprehension. She dropped her head, muttered incoherently, then raised her head again. “What the fuck are you doing here?” she asked.

Dorothy Never — the “Definitist” who is annoyed by Justine’s characterization of her in a magazine article and finds her in this state — is shocked by what she sees. “My voice came mechanically out of my throat.” And this description — from Dorothy’s intrigued, titillated point of view — can’t resist roaming over Justine’s body.

But, for readers, it is Dorothy’s point of view rather than Justine’s predicament that is novel: “I looked and saw the strange, serious woman… she was desolate and ashamed.” Dorothy sees only humiliation and violence, but throughout the book Gaitskill has adeptly woven a description of a growing relationship through such apparently perverted acts (“He pissed on her genitals… it felt warm, almost caressing”).

This is not to say that the sex is not so violent as to be repellent to read. At one point, Justine has a “belt tight around her throat,” and her lips become “so dry they didn’t feel like flesh.” But her description of the sex (which is, crucially, wholly consensual until the man goes “off the deep end”) is a means of revealing more about both women. Justine’s submission, and Dorothy’s resultant horror, are just as key to understanding the novel’s plot and philosophy of oppositions as the women’s “fat” and “thin” bodies.

In This is Pleasure, Gaitskill goes further in exploring the knotty complexities of sexual relationships. One protagonist, Quin, has lost his job because of sexual harassment claims. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that he has behaved inappropriately with many of his female employees. But — in a move that cannot have been politically expedient in 2019 — Gaitskill explores the difference between sexual harassment and inappropriate sexual “play.” Once again, Gaitskill’s tendency to probe the boundaries of “acceptable sex” is not just tawdry erotica — it is a means of encapsulating and challenging the issues she raises in her writing.

For Gaitskill, writing about sex allows her to write about a whole world of complexity: submission and domination, but also joy, intimacy and sadness. Nor is it just sex that allows her to reach these oppositions. Her fiction is littered with people being unbearably hostile to their bodies: binge-eaters; tentative anorexics; girls who pull their hair out; people who pull the hairs on the inside of their nostrils out; children who rip the fur off their cuddly toys. The list could go on. For Gaitskill, it is not just sex which is about ascendancy and submission, and pain and pleasure; it is the very act of existing in a human body.

Gaitskill’s work revels in the “desire and dislocation” of the atomistic 1980s, as the cover blurb on Bad Behavior puts it. Gaitskill writes about cruel and lonely people who can only interact through sex, or so the argument goes. Yet rather than being a portrait of depressing atomization, her work revels in interconnectedness and long-lasting relationships. Characters reappear again and again in stories, and there are subtle links between them all.

I caught myself wondering if “Margot” in This is Pleasure is the same woman as in the earlier short story “Orchid” from Because They Wanted To. Or, if Alison in Veronica could be the “Lily” mentioned in “College Town, 1980” in Don’t Cry — a story which itself already reprises the characters from “Orchid.” This is not dislocation, but rather a complicated web of attachment — attachment which may be permeated by sexual and physical violence but is also marked by friendship, tenderness and family.

After witnessing the violence wreaked on Justine in Two Girls, Fat and Thin, Dorothy gets into bed with her. For a few moments they observe “the conventions of strangers sharing a bed,” but the novel ends with the two girls wrapped around each other. It is not so much sexual as it is a moment of true unity: “her body was against me like a phrase of music.” This is the music we should find in Gaitskill’s work — a music that co-exists with, and is revealed by, the violence she describes so unflinchingly.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.