Early on in her entertaining account of five years immersed in the New York art scene, author Bianca Bosker is informed that, as far as the art world is concerned, because she is a journalist, she is the “enemy.” Given that the job of a journalist is to find things out, then explain and communicate those findings, it is unsurprising that a hermetic, deeply self-protective society like the art world would be resistant to journalistic inquiry.

In reality it’s not just Bosker’s profession that makes it difficult for her to get past art’s gatekeepers, but a whole litany of personal and social failings that are gleefully enumerated by an art dealer early on. Bosker, the dealer tells her, doesn’t dress right; she wears makeup (that shows she’s trying too hard); she’s uncool and asks too many questions. The last is a critical part of her job as a journalist, but it’s also a personal flaw in the too-cool-for-school world of art: if you don’t know already, you certainly don’t want to advertise it.

The dealer’s list is wildly superficial and exclusionary, highlighting everything an outsider might preemptively loathe about the art world — though it must be said that such behavior is not exclusive to those circles. But it’s also an important early lesson in what helps drive the milieu, maybe more than the art itself: context.

In the context of the art world, “context” can mean a variety of things, Bosker notes, from education and personal taste to your “cloud” of associations. Its parameters are often nebulous and subjective, which is also intended to keep them obscure and difficult to decode, creating an endlessly self-reinforcing feedback loop.

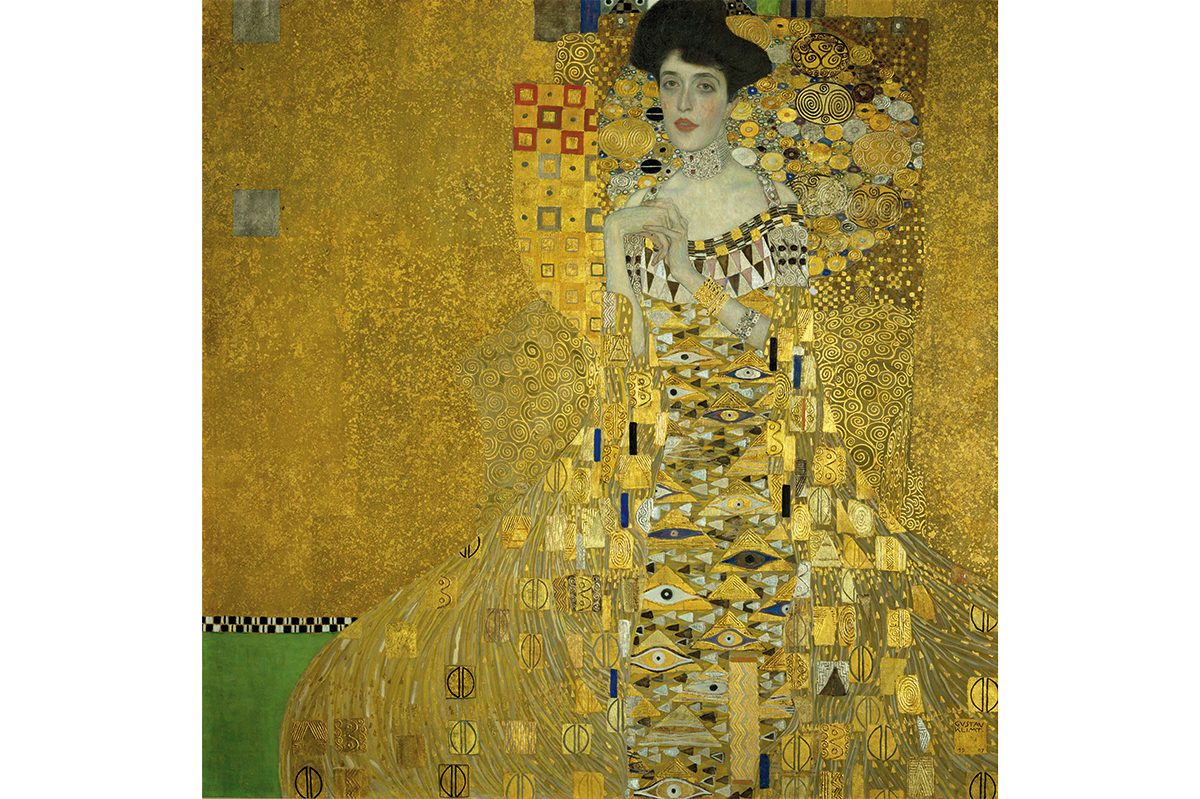

Bosker’s reasons for wanting to try to understand this arcane world are personal as much as professional. As a girl, she loved painting and considered applying to art school, but after graduating and moving to New York, probably the global center for contemporary art, she became alienated from what she had once loved. She recalls her émigrée grandmother, who taught art to children in a displaced persons’ camp in Austria following World War Two, and who imparted to Bosker her love of art. And the art world’s omertà acts like catnip to a reporter. “Nothing gets a journalist’s undivided attention like hinting something is rotten to its core, then clamming up,” Bosker writes of the near-paranoid guardedness she repeatedly encounters.

The sense of secrecy is pervasive, creating an airless atmosphere of exclusivity, which explains people’s undying curiosity about the art world. As one dealer puts it, mystery builds intrigue — which, we infer, also drives prices. Protecting that mystery infects everything, from press releases that read like riddles to extreme vetting of anyone who enters the ecosystem. (Ordinary “Joe Schmos,” Bosker is told, need not apply.) But any world whose default mode is discretion will also be rife with abuses, not to mention financial chicanery. (“We’re all white-collar criminals,” one dealer remarks “breezily.”) When boundaries don’t exist, when the personal is also the professional, exploitation is par for the course.

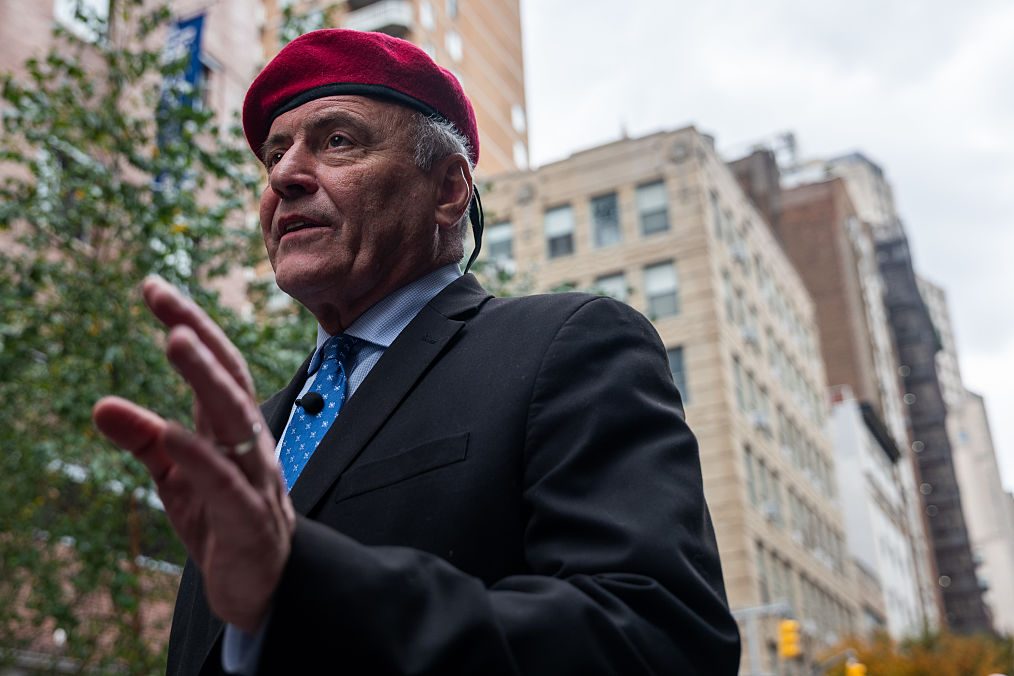

Mission stated, though, Bosker jumps into finding out about art. She works for two different galleries specializing in the work of emerging artists (the “blue chip” spaces presumably impenetrable) and sells art for one of them at a satellite fair of Art Basel Miami Beach. She assists an artist with a growing profile, stands for hours as a guard at the Guggenheim Museum, shadows a pair of collectors and attends countless studio visits, exhibitions and fairs, as well as a conference in Belgium on the “visual science” of art. She primes canvases, paints walls and even volunteers to have an artist sit on her face as part of a conceptual performance. Bosker’s enthusiasm, her curiosity and tenacity are infectious. While plenty of art-world denizens condescend to her or keep their distance, some are happy to consider the rules and absurdities of the wider systems in which they operate. Bosker has her frustrations at the start, but they come from wanting to understand rather than criticize. (The tartest zingers come from insiders anyway: “If I had to choose between going to Art Basel Miami and dying in a plane crash, I’d pick going down in flames,” says an unnamed “veteran.”)

As a snapshot of the art world now, or at least up to the pandemic, Get the Picture adds to the surprising number of books and films set in this clubby world. These range from Sarah Thornton’s 2008 anthropological book Seven Days in the Art World, released at the end of the boom years, to filmmaker Ruben Östlund’s savage 2017 satire The Square. It is a world deeply resistant to change, but not immune to it. Financial insecurity remains the norm; figurative art becomes covetable again. Social media, especially Instagram, offers a route in for some, as well as a more accessible look at the networks that undergird the art world. As in the wider world, gossip and speculation spread fast online and money moves almost as quickly, which can be devastating for an artist in the early stages of a career. Perhaps it would be more accurate to call it an “art system” than a world, a “machine,” as it is nicknamed.

But what drives people’s interest in art, as opposed to what might drive their interest in the goings on of the art world, is, in Bosker’s telling, profoundly linked to what makes us human. One of the book’s best descriptions of being around the “beautiful things” in a museum comes not from an insider but a museum guard, who says, of proximity to that beauty, that “it enlightens you, it makes you feel — you know what? It gives you that feeling of being rich.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply