If there is a central message in Harmony, it is that old cliché that evil flourishes when everyday people stand by and do nothing.

That idea is returned to repeatedly, with increasing angst, as the central characters in the musical get swept up, and finally tossed aside, in Nazi Germany.

Harmony revives the true story of the Comedian Harmonists, six men — three Jewish, three Gentile — who created an ensemble in 1927 during the waning days of the Weimar Republic. The group, who melded physical comedy with singing, sometimes using their vocal cords to mimic entire orchestras, became a surprise hit. They sold millions of records, appeared in movies, and performed worldwide.

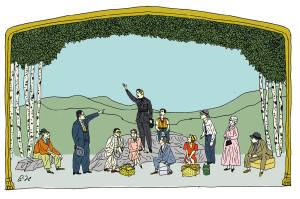

Indeed, composer Barry Manilow and his long-time creative partner Bruce Sussman, who wrote the book and lyrics, start Harmony at the height of the prototypical boy band’s success: at a giddy 1933 concert in Carnegie Hall. It is a fitting beginning for a production that recently moved to Broadway after a critically acclaimed 2022 run at the downtown National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene. Once again, the Harmonists are center stage.

The show quickly introduces the motley crew of singers, who answer an ad placed in the newspaper by Harry (Zal Owen), an unassuming musical maestro. It is a credit to Sussman and director-choreographer Warren Carlyle that each character feels individual and well-sketched, yet also seems a natural creative fit into the sextet. With palpable on-stage chemistry, and an ability to riff off each other, they genuinely appear friends. There’s the wealthy medical student Erich (Eric Peters), who has developed a dread of blood; a Bulgarian called Lesh who loves redheads (Steven Telsey); Bobby, a business-minded bass (Sean Bell); and the rapscallion whorehouse pianist, dubbed Chopin (Blake Roman). Lastly, the sweet, optimistic Josef (Danny Kornfeld), who is nicknamed Rabbi. It is the older Rabbi, played by Broadway veteran Chip Zien, who acts as narrator, conducting the action on stage as he shares his memories of the band’s meteoric rise. At first, Rabbi revels in nostalgia, even going so far as donning wigs and hats to play different characters in his own story, all with a knowing wink at the audience. “We were hot as horseradish,” he proclaims cheekily at one point. As the fate of the band becomes clear, however, he descends into anguished monologues.

Zien’s Rabbi signals both mistakes made by the Harmonists — who had a chance to stay in New York but chose to return home to Germany, radically underestimating the rise of fascism — and the compromised moral compass of ordinary citizens.

At times, this veers into grief-stricken regret that he didn’t do more and, like many Jews, that he didn’t read the writing on the wall in time. “You could have stopped it. But no! nothing. What were you thinking? Wasn’t it clear? Didn’t you know? No, yes, no… You did nothing,” the older Rabbi shouts, rather than singing, over the music in “Home.”

The songs, too, shift. There is a sense of real happy-go-lucky fun in the band’s centerpiece “How Can I Serve You, Madame?” But it dissipates into something darker: when the Nazis start to notice the Harmonists, the singers rebel by dressing up as creepy marionettes for a concert in Copenhagen, creating the satire “Come to the Fatherland”:

Who cares how the wind may blow We just string along Life is simple when you know Having rights is wrong

And while the Carnegie Hall title number “Harmony” gives a sense of the music the real Comedian Harmonists performed, Manilow quickly leaves the old-timey genre behind for more classic Broadway numbers. Standouts include the gorgeous “Stars in the Night” and the lament “Where

You Go.” The latter, sung beautifully by Rabbi’s wife Mary (Sierra Boggess, a stoic, supportive Gentile) and Chopin’s wife Ruth (Julie Benko, a fiery Jewish Bolshevik), is heartrending.

But Ruth, while performed by Benko with guts, is also a problem that threatens to engulf the whole musical. She is not based on a real person, as other characters are, but is a composite (the real-life Chopin married multiple times). She also receives the worst fate of the bunch, ending up in prison trying to cross the border, before disappearing for good.

Her fate provides some of the most haunting lyrics (“Where you go/I will go/In your dreams/in the shadows”), yet she also feels like a sacrificial lamb there merely to raise the stakes. Worse still is a scene in which Rabbi spots Hitler, on a train and freezes, rather than assassinating him. In manufacturing drama, and in trying to make the Comedian Harmonists’s story even sadder than it was, Manilow and Sussman merely make it feel overegged.

The true story is plenty: that, during a time of monstrous persecution, there was a band dedicated to joy that consisted of Jews and Gentiles. They lived in creative and personal harmony, but were pulled apart, their records banned, and their members scattered. The obliteration of art and the destruction of friendships in the Nazi era is tragedy enough.

Booking to September 1, 2024, Ethel Barrymore Theater. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.