Every December, I make my way to the orgiastic display of wealth and ostentatious show-boating that is Art Basel in Miami. I go primarily to keep my finger on the racing pulse of our culture of conspicuous consumption and hedonism, and also because of an unhealthy fascination with human irrationality at scale, the kind of irrationality which drives bubbles. The high end of the global art market has always been a curious blend of vanity, self-absorption and what to every untrained eye is quite clearly commercial sophistry. Yet it persists and continues to grow, with worldwide sales for 2018 reaching $67.4 billion, up from $63.7 billion in 2017.

Miami is, in many ways, the perfect host city to this bedlam of excess, having somewhat outgrown its kitschy, cocaine-fueled art deco vibe and matured into a serious cultural center and real estate hub. Now in its 18th year, the premier art trade show has metastasized into an unwieldy morass of satellite fairs, museum events and exclusive parties rife with corporate tie-ins, most of them overrun with women in ‘New Year’s Eve chic attire’. There was a NSFW party with a vagina bouncy castle. Someone’s massive hoarding problem that masqueraded as a treatise on feminism, hyper-consumerism and environmentalism was successfully sold at the new Meridians exhibit. The fashion brand Diesel sold T-shirts for $5 million (it came with a free condo). Animatronic snails crawled around the main Miami convention center floor leaving fake slime in their wakes and, at one point, I watched scores of people scrutinize a looping video of a man wrapping his uncircumcised penis with a vine plucked from a tree deep in the Brazilian rainforest.

All of this was drowned out by The Banana and the shenanigans that followed, from when the performance artist David Datuna casually ate it front of a gasping crowd in a piece that he christened ‘Hungry Artist’, to the subsequent ‘vandalism’ of the banana-less wall space in which the phrase ‘Epstien (sic) didn’t kill himself’ was scribbled in red lipstick.

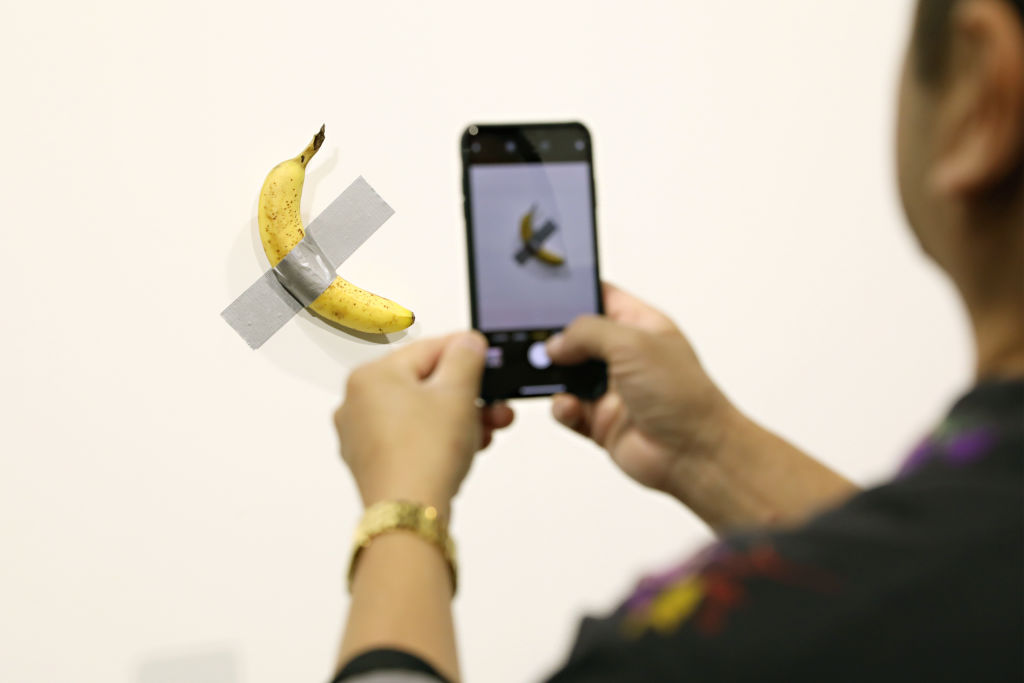

Art Basel rarely receives national coverage, let alone the cover of the New York Post or prime time network TV. But this was no ordinary year. Images of a banana duct-taped to a wall and the headline that it had sold for $120,000 went viral on social media; indeed, they even dominated conversations at the fair itself. Since Duchamp’s lavatory, contemporary art has often teased the masses with various iterations of the question ‘But is this art?’ Maurizio Cattelan’s fruity work, intriguingly titled ‘Comedian’, is so facile that it drew reactions of incredulity, scathing disbelief and derisive outrage. Tweets mocking the artwork emanated from both official brand accounts and average Joes who now insist they have what it takes to be an artist. That the banana was sold twice and later eaten by a New York-based performance artist only further underscored the flippancy with which the ‘1%’ view the value of $120,000 — more than twice the median household income in the United States.

Many online commentators lamented the vacuity of modern art and the need to restore aesthetic standards, which might hint at a backlash against relativism and postmodernist attitudes. #BananaGate seemed to also have triggered the same wave of anti-elitism and distrust of the powerful that is fueling populist movements such as Brexit and the gilets jaunes protests that have been raging in the streets of Paris for a year now. Like the mortgage bundles and credit default swaps that ushered in the financial crisis of 2008, the duct-taped banana is an inside-joke among the high priests of the art establishment, a complicated instrument that enriches the Champagne-swilling, art-collecting crowd who then tell us unsophisticated philistines that they couldn’t possibly understand the subtleties.

‘Comedian’ succeeded wildly in provoking emotion, generating hype and promoting discussion. It allowed Art Basel to monopolize national news coverage and online discourse, and it drew crowds so large that the Perrotin Gallery which hosted the work, decided to remove the new duct-taped banana entirely on the last day of the fair for crowd control and safety purposes. That left an empty wall and the perfect opportunity for Roderick Webber of Massachusetts to make the morbid internet meme that ‘Epstein didn’t kill himself’ take on a life on its own in reality, at a prestigious art show inundated with the privileged class.

‘This is the gallery where anyone can do art, right?’ Webber said after being confronted by a security guard, according to the Miami Herald. As he was escorted out of the convention center, he yelled, ‘if someone can eat the $120,000 banana and not get arrested, why can’t I write on the wall?’

It’s a good question. If art can be everything and anything, can anything and everything be art? Webber’s question, Datuna’s consumption of a $120,000 artwork, and the absurdity of Cattelan’s duct-taped banana allude to the idea that contemporary art has always claimed to be about subversiveness and decentralizing authority, defiantly showing its middle finger to its own pompous art world while satirizing the ills of society.

The banana, with its phallic shape bolstering its inherent silliness, has long had a storied place in art history, lending itself to iconic pop culture status after Andy Warhol plastered a cartoon version on the cover of the first Velvet Underground album (1967). Several contrarians espoused the ‘eye of the beholder’ argument, explaining what they saw in the Cattelan work a hammer and sickle, or a symbol of silencing the patriarchy, and even freedom by way of ‘suppressing banana republics’.

In an age of trolling, Maurizio Cattelan performed the ultimate troll. He was in turn trolled by Datuna. Then we were all trolled by Webber. Cattelan’s body of work has often elected amusement and horror, from the time he dug a coffin-shaped hole in the floor of a museum’s main gallery, to the sculpture of Pope John Paul II being hit by a meteorite, to the full-sized Hollywood sign he erected over the largest rubbish dump in Sicily for the 2001 Venice Biennale. These are cynical, crude and confrontational works, much like the characters in Sacha Baron Cohen’s films. Arguably, they perform the same social function and service, albeit less entertainingly.

The exorbitant price tag and the willingness of buyers to fall for #BananaGate exposes the injustice of a world in which 9.9 percent of the population lives on less than $1.90 a day and income equality has reached a zenith in the United States. The frenzied hype over the irreverent stunt underscores how eyeballs and attention are the new currencies. They determine what gets talked about, and worse, what will go into the history books. How many in the general public knew Cattelan’s name before this?

It’s hard to see all of this and not view Elizabeth Warren’s proposed wealth tax favorably, or harbor an impulse to perhaps bring back the guillotine. To the public, the $120,000 ‘Comedian’ is just a banana, likely to blacken in a few days, taped to the wall by an artist who hasn’t produced anything for a major art fair in 15 years. What was sold is really the ‘concept’, an idea made official by a Certificate of Authenticity, a certificate of an artwork that doesn’t actually exist in physical reality because it was eventually plucked off the wall and consumed by David Datuna. You see, the Emperor is naked and none of the Masters of the Universe dare to tell them.

But Maurizio Cattelan, David Datuna and even Roderick Webber, in a way, did.