Ashton Applewhite is a leading American ‘inspirer’ on how to make the most of being over the hill. She has followers to whom she dispatches her inspiration by blog, YouTube, TED, magazine column and talk-show interview. This Chair Rocks first came into the world, three years ago, as a ‘networked book’. It now presents itself in a form more congenial to ‘olders’ as Applewhite likes to call them. Whether to go large print must have been an option considered by its current publishers.

Applewhite’s previous book-qua-book was Cutting Loose: Why Women Who End Their Marriages Do So Well. ‘Upbeat’ is her middle name. There is one passing reference to her ex in This Chair Rocks and we gather she now has a partner, Bob. All we are told about this not-spouse is that he gets very angry if anyone calls him grandpa.

The occasional allusions Applewhite makes to herself can be startling. ‘It was a bad day,’ she wistfully recalls, ‘when I was diagnosed with periodontal disease and vaginal thinning in the same morning.’ The older’s little helpers put all right.

A largish section of the book is devoted to ‘dating for olders’ and how sex — no rush and tumble, more caress and fumble — can be better than it was when hormones raged hotly. And if you’re asexual by nature or choice, well, regard age as a haven. Peace at last.

As olders will fondly recall, the allusion in Applewhite’s title is to the classic Jack Teagarden number ‘Old Rockin’ Chair Got Me, My Cane by my Side’. In one sense the amiable Dixieland trombonist lives forever, through his recorded music. But he died in the flesh aged 59.

During the 20th century the average American (and Briton) gained an extra 30 years of life. Longevity rules. In 1969, when longer life expectancy was becoming increasingly visible, the geriatrician Robert Butler came up with the term ‘ageism’ for discrimination against the new old. Both versions of Applewhite’s book are dedicated to Butler, ‘who kicked the whole thing off’.

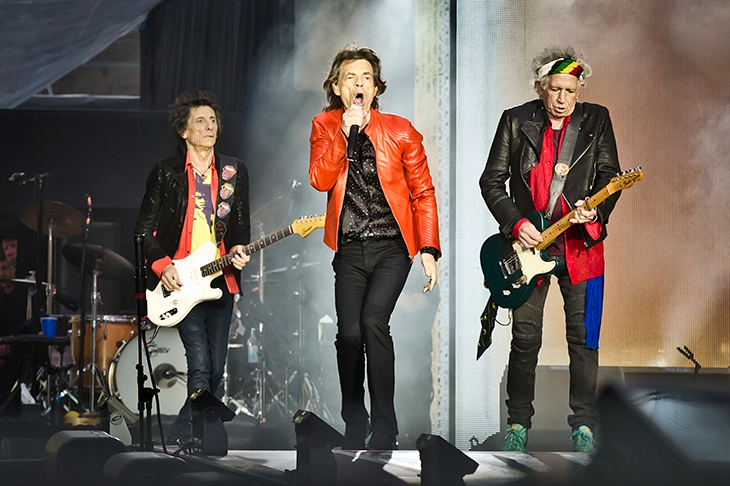

Applewhite rocks, we apprehend, not like Teagarden but like the 75-year-old Mick Jagger. After a night’s dancing, she has to place ice packs on her somewhat tricky knees. Probably Sir Mick does the same nowadays after a live concert.

This Chair Rocks opens with defiant frankness. ‘I’ve never lied about my age — I have no problem saying “I’m 66” loud and clear.’ Applewhite despises those olders who would pass their wrinkled mutton off as botoxed lamb. She is now well retired from her career position at New York’s American Museum of Natural History but even more active as the sage of age. All retired olders, she recommends, should take up an ‘encore career’, as she has.

Applewhite’s thesis is that age, in this day and age, is not Shakespeare’s glum ‘sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything’. Take heart, she enjoins, from surveys having proved that ‘people are happiest at the beginning and the ends of their lives’. ‘Even as the population ages,’ she asserts, ‘dementia rates are falling — significantly.’ Pessimists may see as significant the fact that since 2017 Alzheimer’s and dementia have become the leading causes of death in the UK.

Applewhite disdains swankpot olders who climb Everest aged 80 or bungee-jump aged 90. Exemplary for her are those who accept and adapt, constructively, to bodily and mental decay. She would hail the centenarian Diana Athill who describes, in her last book, the sheer fun of driving her mobility scooter like a panzer through the Ardennes in 1940 to get front view at art galleries.

Some of Applewhite’s cheeriness is, frankly, bonkers. ‘Dementia can liberate,’ she declares. How, exactly? Because it delusively transports you back to your happy past. It’s not a trip Saga would endorse — the Alzheimer nostalgia cruise.

Much of Applewhite’s book is, like this, stratospherically over the top. Nonetheless her audacious address to the problem of aging has its attractive, and at times very useful, aspects. The old, she exhorts, should ‘push back’ — her favorite admonition. They should ‘Reject the bogus old/young binary!’, ‘Aim for agefulness!’, ‘Realize that aging is not a disease!’ The older should, above all things, avoid sedentarism (that old rockin’ chair again). Immobility — of mind and body — is a surrender to ‘internalized ageism’. See yourself, in younger years (she has sprightly 66 in mind, we suspect) as ‘an older in training’, like a boxer with a tough fight ahead. For those on the way to losing, as we all shall, our last fight she advocates ‘doulas’ — mortality midwives.

The relentless cheerfulness of This Chair Rocks grates. But good cheer, Applewhite would retort, is tonic — an elixir of life, even. One of her many feelgood statistics is that ‘People with positive perceptions of aging actually live longer — a whopping seven and a half years on average.’ So, you growing cohort of olders, whop away, live long and rejoice you’re old. Then die.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.