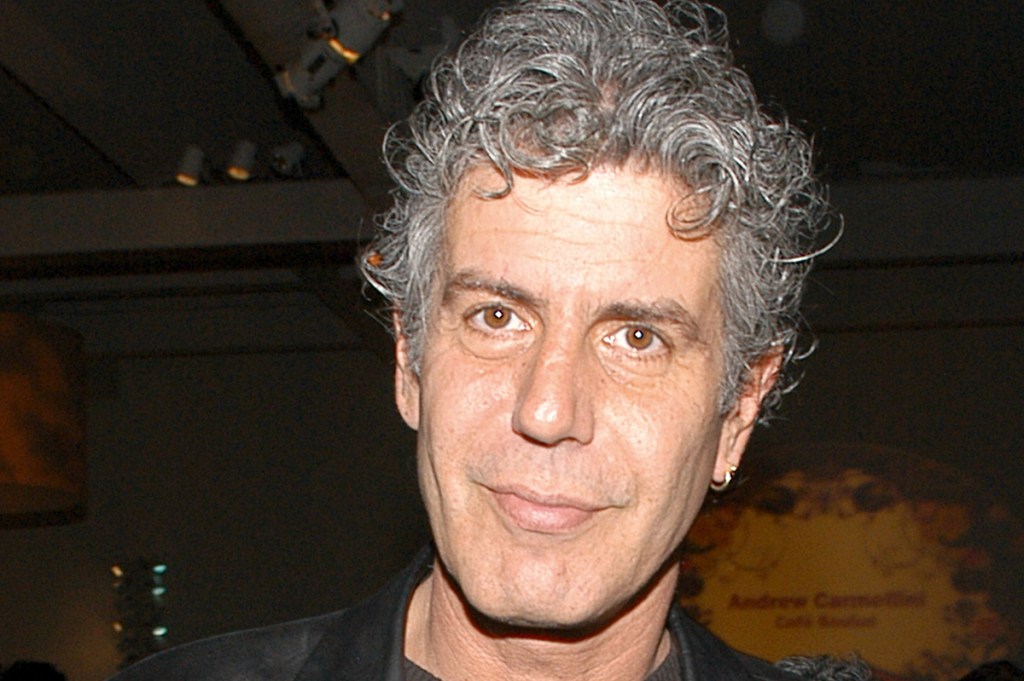

Charismatic, handsome and with a great white shark’s feral cool, Anthony Bourdain was someone that everyone wanted to be. The chef, writer and TV presenter described the premise of his award-winning shows, No Reservations and Parts Unknown, as “I travel around the world, eat a lot of shit and basically do whatever the fuck I want.” They cemented his image as a gadabouting, kamikaze gourmand.

Bourdain scarfed down andouillette and warthog anus, drank sun-bear bile and polished off the still-beating heart of a cobra, plonked into a shooter of Vietnamese firewater. He showed Barack Obama the correct way to slurp bún chả noodles on a steamy Hanoi side street, and he and his team watched from their hotel pool as Israeli jets strafed downtown Beirut during the 2006 invasion. “I have the best job in the world,” he told the New Yorker when the magazine caught up with him.

Bourdain wasn’t shy about his tastes. He liked hard liquor and offal, obscure 1970s punk bands and Brazilian jiu-jitsu, tattoos and younger Italian waitresses. In his fifties, then a recovering junkie who’d spent two decades addicted to heroin and cocaine, he somewhat unexpectedly became a father. His daughter Ariane was a rebuttal to the rackety, criminal chaos of his earlier years. He was poleaxed by the contentment and calm she brought him. Yet on June 8, 2018, while on location in France, Bourdain took his own life. Everyone wanted to be Anthony Bourdain – except, it seems, Bourdain himself.

How to unpick that riddle? One answer is The Anthony Bourdain Reader, an exhaustive, overwhelming gathering of his writing. Some of it has appeared before, including in his bestselling memoirs Kitchen Confidential, Medium Raw and A Cook’s Tour, but more than half of it has never been published. The extracts range across his career – from his 18-year-old “gap year” diary as he traveled, lost, lonely and bored, through France in search of Hemingway-like grit, to the very last piece he wrote before his death: a melancholic and surreal vignette in which an estranged married couple meet in an anonymous bar and end up accidentally shooting the barman.

It also contains fun, slighter stuff. For instance, there are his tips for successfully hosting a party, boiled down after years catering events. (In essence, keep a ready supply of pigs in blankets to hand: “No one will give a fuck once you send out those little doggies.”) His advice on a killer Thanksgiving gravy is that it’s all about the roasted turkey giblets.

But the circumstances of Bourdain’s death loom large over every page of this collection. You end up playing a ghoulish detective game, parsing every world-weary joke or performative rant for an explanation. And this material isn’t hard to find. A large part of Bourdain’s persona – at least early in his public career – was his tousled ire, an ex-junkie’s recognition of life’s fundamental unfairness.

One of the strongest, and saddest, pieces in this collection is Bourdain’s lengthy account of the trip he and his brother took to recreate their childhood holidays in south-west France. (Bourdain’s father was French, though he didn’t grow up speaking the language.) Stumbling after memories of sandwiches on the beach – “the texture of the crusty baguette, the smear of French butter, the meat, the inevitable grain of sand between the teeth” – the brothers, now well into middle age, instead prowl through the rain-lashed, off-season resort in search of their younger selves. It’s Beckettian in its bleakness; it punches you in the gut. “I’d come to find my father,” Bourdain writes in the conclusion. “And he wasn’t there.”

The danger of any posthumous collection – however complete – is that it ends up feeling partial. It becomes biography as zoetrope: a life in snatches. There’s Bourdain the restless kid, kicking against his comfortable middle-class upbringing; Bourdain the addict; Bourdain the doting father; Bourdain the elder statesman of TV, grumbling about the tedium of filming. Yet what struck me most when I was making my way somewhat effortfully through the book – Bourdain could be an incandescent writer, but he could also be very boring – was the extent to which he himself would have scoffed at it. Throughout his writing is a recognition of the impossibility of getting the pith and grain of life onto the page, or the TV screen. A good meal, after all, is ephemeral, unrepeatable – and therein lies its magic. Trying to set down that magic is a foolish and frustrating task.

So why bother at all? I think the answer is that writing – at its best – offered Bourdain the same pleasures as cooking. It promised immersion, a chance to exercise his blistering perception, to lose himself in rhythm and flow. The finest work here shows that beautifully. The collection rightly reproduces his scalding, career-making essay for the New Yorker – “Don’t Eat Before Reading This” – which plucked him from obscurity, aged 44, and set him on the way to stardom.

But my favorite pieces are extracts from Kitchen Confidential and A Cook’s Tour. The first recounts a busy shift at Brasserie Les Halles in New York, where he was executive chef before he was famous; the other is an account of careening down Highway 1 – “the Highway of Death” – in Vietnam. They both have the same marvelous speed and pace: an intoxicating immediacy. In one, he’s being kicked in the balls by a manic lunch rush; in the other, he faces the prospect of fiery death in a car accident. But here, in the moment, he has no time to think, ponder, or muse. He can simply be himself, rather than self-consciously playing the character of Anthony Bourdain. He was happiest, he wrote, when riding a moped through the blaring chaos of Southeast Asian cities – anonymous, one vehicle among the press of thousands, eyes wide open and hungry.

A few years before he died, Bourdain began reading the essayist Michel de Montaigne. He fell in love with Montaigne’s work and got a tattoo of the writer’s motto in Ancient Greek on his forearm. “I suspend judgment,” it read. It’s a mantra he tried to live by – and, when we consider his life and legacy, one we might reflect on too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 22, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply