People offended by name-dropping are absolutely no fun. I’ve experimented with this concept on five continents — OK, four: Antarctica’s social whirl isn’t what it might be — and those who roll their eyes at shocking new developments in the world of celebrity are just the worst. Not content with having zero information to offer, they diminish what is given, and in a more efficient world such bores would be carried at high speed to the guillotine. I take my cue in these matters from the great name-droppers of all time, who, in no particular order, are James Boswell, Pope John XXIII, Lee Strasberg, Truman Capote, Nelson Mandela, Andy Warhol, Nicky Haslam and His Majesty King Charles — and that’s before you even reach the world of altitude-sick politicians, people such as the late Henry “Chips” Channon, a man who couldn’t wash his hands without making reference to Pontius Pilate, Lady Macbeth or the man who invented Palmolive. Name-dropping, like baby-sitting, is a word without equivalent in either German or French, and its domination by men is really quite striking, as I once told my friend Karl Lagerfeld.

My main value to my clients is that I never speak to the press, and that’s the God’s Honest Truth. My dear mother, a fan of astrology and dog trainers, told me I had a Copernicus Complex (the world revolves around me) and that I adore being in charge of the information. Mummy’s a legend but doesn’t actually know me. I do share what is shareable, but I put myself at the centre of things because that’s where my clients expect me to be. It’s troubling, I admit, that there are galaxies out there, suburbs, parts of Belgravia for heaven’s sake, where people are definitely wearing the wrong thing. I hate it, but I’m here to help. I’m a stylist, or, as I much prefer, an image architect. Let me just get it out of the way and tell you that half the people you follow on Instagram are in your face because of me. Entre nous, I can promise you Timothée Chalamet could scarcely tie his shoelaces before he met me, to say nothing of Zendaya, the present Princess of Wales, and, recently, her husband’s uncle.

I was over at Windsor Great Park the other day and I brought some “insane pulls” into Adelaide Cottage. William’s going through his rugged/reset phase, which is way beyond the universe of chinos, I must say. I brought him over a rail of on-trend gilets, selvedge denim, slimming knitwear and a couple of Charvet neckerchiefs. They might not take. His tastes are a tad NGO fieldworker, morally serious and strictly post-fun, but it’s my job to awaken those parts of my clients they thought had expired. It’s not easy with the major royals, but Kate is an absolute doll-face beyond. I met her back in the day, when I was working for Alexander McQueen and we were pulling together that dress. She’s wicked, actually. For Christmas I’m giving her a candle that smells of Belfast. People think my clients don’t have problems. Let me tell you, they only have problems, and it’s generally the women who sort things out. Not always. Don’t get me started on all matters Californian. I won’t go there. Being an image architect is often about worrying a dark problem into daylight.

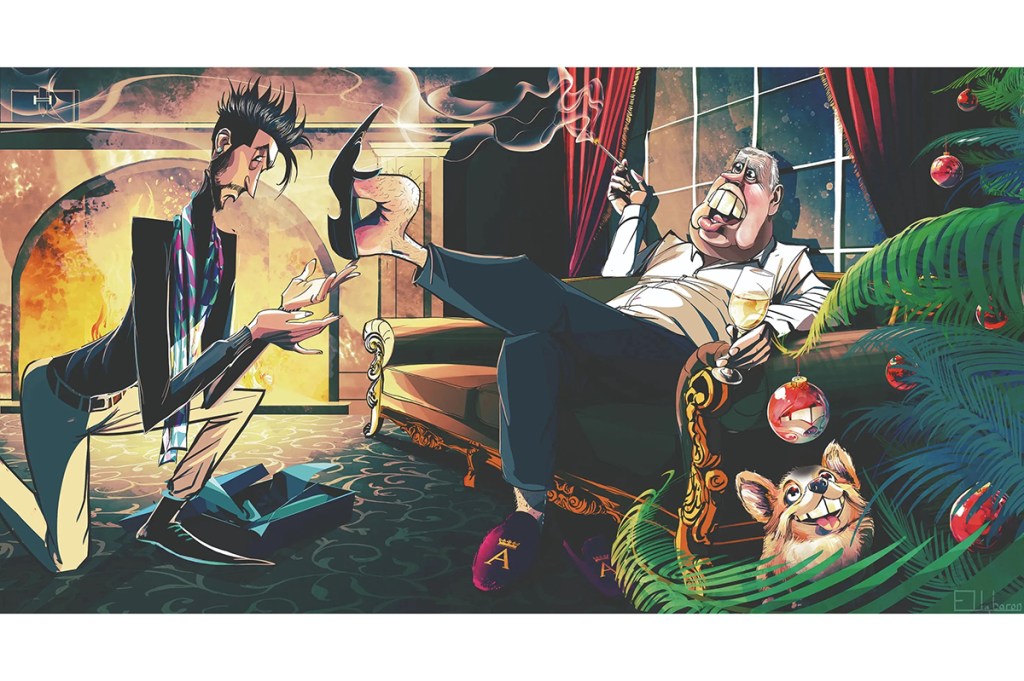

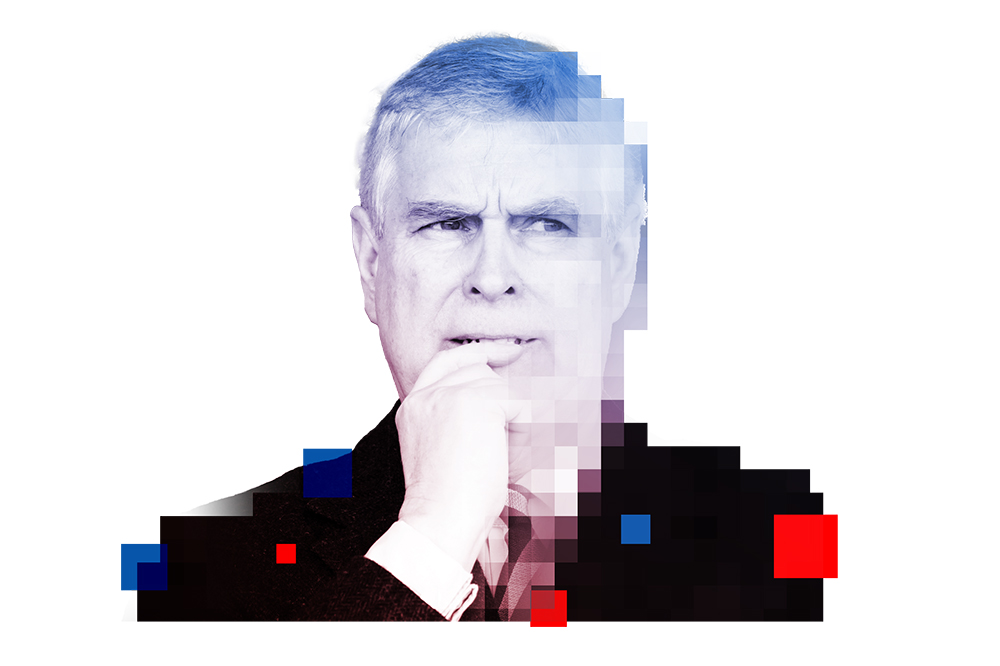

But listen — the Uncle. He has lately turned that Lodge into a mausoleum to future prosperity, but he cuts a lonesome figure under the chandeliers. I drove over there the other evening at about eight o’clock, fresh from a party for Chanel Beige. It wasn’t that cold but every fireplace in the house was blazing. “Hello, you,” he said when I entered the gothic drawing room and found him standing in monogrammed slippers. He was rather dwarfed by a 12ft Christmas tree, the branches showing a contagion of red baubles.

“Your Royal Highness.”

“Very good,” he said.

I mean, what can you say? The poor bloke was on his arse. But I could see that evening he was definitely on his way back. He had the survivor’s glint, a certain arrogance flushing his ample cheeks. My job, strictly speaking, is to improve a client’s image in the face of life’s traditional setbacks. “Yes, of course, Sir. As you prefer.”

“But I suppose you’re Liverpudlian,” he said. “I knew a few chaps like you on the Invincible. Northerners. Mental cases, quite frankly. But bloody loyal. And I expect the same sort of thing from you, Oliver.”

“Thank you, Sir.”

“You’ve pretty much lost the accent. A few little barbarisms here and there, in your speech I mean. Will you have a drink?”

“Sound,” I said.

He probably should be on the wagon. I mean weight-wise. If I was in charge he’d be on a weekly jab of Ozempic and a bit of wholegrain toast. As it is, he puts away the white wine as if abstinence went down with the Belgrano. He held up a 2020 Chablis Grand Cru Le Clos. “King of the cellar,” he said, handing me a full glass.

“How delicious.”

He sniffed into his own glass. Then he moved towards the fireplace and looked up at the framed portrait. George IV, I believe.

“Don’t your people say ‘bevvy?’” he said, turning back to me.

“We do. Though for me that’s a long time ago.”

“And ‘bifter.’ Is that what your people call a cigarette?”

“I believe so.”

“How wonderfully absurd,” he said. “Bifter. You got any?”

“Cigarettes. They’re in the car. And I have a little joint if you want it.”

“Capital!” he said.

I brought two holdalls of clothing samples back with me, as well as the cigs and the spliff, ready-rolled in an Hermès purse.

“Trust a Scouser to be peddling drugs,” he said. “I absolutely love all those words your people use. Tell me more of them.”

“For food we say ‘scran.’”

When he said “yes” it came out as “ears.” The royals love it when you play along with them and make things funny.

“I suppose the North is all correct now,” he continued. “Full of people who think that if one owns a car one ought to be brought before a firing squad.”

“Environmentalists.”

I always felt I could push it a little with Andrew. It’s merely a question of judging the correct moment and making it casual.

“Tree huggers,” he replied. “Bloody absurd.”

After that we walked towards his den, passing along a corridor filled with military stuff, including the sword that accidentally cut Ed Sheeran’s face. (Long story: party. Young People. Knighting ceremony gone wrong.) The den had two sofas, a writing table and a rather imposing oil painting of the late Queen Mother, which came very prettily to life with all the dancing flames jumping in the fireplace. A book was sitting on the desk, a copy of Wolf Hall that I’d given him the last time I was here. Beside it was an open DVD box set of the same title. He wasn’t much of a novel reader but now that Sarah was writing them he thought he’d better try.

I laid down the bags. He went to a side table and brought over a heavy ashtray and we sparked up. “Fashion people. You’re all reprobates,” he said. “I had a group of them to the Palace when I was trade envoy.”

“Oh, yes. Orla came. And Net-a-Porter. I remember it. Half a dozen fashionistas and your late father gadding about taking the piss.”

“Ah, yes,” he said. “One misses Phil dreadfully. A true serviceman.”

I hesitated, then pushed on. “Oh, really? He served in the war?”

Andrew sighed, like I’d seen him do many times. He was always on the brink of throwing you out. “My father was a midshipman in 1940, you terrifying oaf. He served on HMS Ramillies, HMS Kent and HMS Shropshire. Then with Valiant in Alexandria. For valor, he was mentioned in dispatches and he went on from there. Left to his own devices, my father would most probably have become First Sea Lord.”

“I do apologize.”

Some people receive apologies like they really deserve them. “Forgiven,” he said. “People generally just don’t have the information. There are things they don’t know. Things they will never know. My family is my family. For a long time, it was just the six of us. And I think of that now very often, just the six.”

When I opened the bags, I brought out a few shirts from Turnbull & Asser. My friend wasn’t really my friend, but he needed help, and I think he trusts me because his girls speak well of me and I helped one of their husbands. It was not long before Christmas, and it emerged that Andrew would be staying on at the Lodge after all, and that maybe at last there were things to be cheerful about. “I don’t like these shirts,” he said. “What would one even call these colors?”

“Lavender, Sir. And the second one is burnt orange.”

“Repulsive.”

“Softer tones,” I said. “More fun, perhaps.”

“I don’t approve of ‘fun.’”

I tried not to raise an eyebrow. A man is entitled to recover in his own way and say what he likes about himself. Then it all ascended into name-dropping, which of course cheered me up no end. “David Beckham,” he said, “once told me his wife would make him wear things just to see the reaction it got in the press.”

“What larks.’

‘Terrifying. But some people have rather determined wives. My friend Bill Clinton has one of those, too.”

“I think we might return you to your open-necked era,” I said. “Maybe not the orange. But inclining away from the business shirt.”

“No. Let me see some ties.”

I unrolled a group from Drake’s. Dots, stripes, but rather more democratic than the coats-of-arms things he usually likes. He chose a pair of Lobb shoes but turned down several silk shirts from Edward Sexton. “This is all a bit Koo Stark,” he said. “And the last thing one wishes to revive at present is the, em… Randy years.”

“Yes, Sir.”

“It’s all quite mad, of course,” he added.

“Indeed,” I said, folding away the shirts. “But we’re on a journey.”

“I beg you, please don’t say that,” he replied. “The country might be on a journey. The world might be. But I’m staying right here.”

When I’d put everything away he poured more wine. The lights were twinkling on the Christmas tree and I began to worry about driving home. But when the major royals are in the mood you have to go with it.

“Cilla Black,” he said quite randomly. “I always thought she was rather nice.”

“Oh, very.”

“Always banging on about ‘the pride of Liverpool.’ I mean, why do the people in that city need to have so much pride?”

“I don’t know, Sir. Good question.”

“I mean, one might become rather bored of being proud.”

Two corgis came ambling into the room. One of them jumped on to the sofa and snuggled with His Royal Highness. I’m not really a dog person, so I kept to my seat as Sandy and Muick were rather formally introduced to me. “How do you do?” I said to the one at my feet — “Sandy,” the Prince said.

After the smoking, I thought I’d take charge, cheekily, and I withdrew a Cire Trudon candle from the bag and lit it, putting it on the mantelpiece. I tend to warble in the Prince’s presence. “This candle is called Joséphine,” I said. “Think of the perfect royal garden, perfumed with Turkish roses and Egyptian jasmine.” The dogs went mooching around the room and one of them, Sandy again, appeared to be examining its mauve face in one of the low-hanging Christmas baubles.

“Listen,” Andrew said at last. “I have a problem.”

“Oh, yes, I’m all ears.”

“It’s Christmas. I want to thank my elder brother. It’s complicated.”

Sandy growled and bared his teeth at the bauble. He leaned onto his front paws as if assembling himself for battle.

“You need a gift?” I asked him.

“Precisely.”

“For Christmas.”

“That’s right.”

“For the King.”

“Quite so.”

He stared off in the way that dog lovers do, as if the pets might represent a world of simple solutions, beyond the vanity of human wishes.

*****

The next morning I had a mild hangover. I’m not used to drinking any more, and his driver was picking me up at Albany at two o’clock. If you ask me, I’d say Andrew was a bit on the lonely side, craving a task, a duty even, or an eventful day out in London with some purpose. He was relieved to be staying on at the Lodge and he wanted to make the hunt for a gift into a rite of passage, or something like that, a marker of his great intention to move on with his life. It would cost him (or somebody) to maintain tradition, but he also wanted, I think, to consolidate his memories. And I could help. In my job, I can make a newness of people’s old wishes. As my Irish mother used to say with approval, “You never got a new arse and forgot your old one.”

I telephoned my friend Nicky for advice about the problem. Andrew had to buy his brother a present. I couldn’t say much more. “I mean, what sort of present are you supposed to buy the monarch?”

“How about a certain tea towel? Fifty quid at Selfridges.”

“I’m serious, Nicky.”

“I already sent one to Camilla. She’s so adorable.”

“By the way, I’ve got an entry for next year. Monogrammed slippers.”

“Definitely common,” he said. “They do them in Next. As we speak, children are parading up and down Oxford Street in leather jackets and velvet slippers.”

I had to ring off because of the time, but not before Nicky told me about the traditional nightmare of royals and presents. He said Wallis Simpson couldn’t say no to a brooch but it had to be Cartier, preferably emeralds and diamonds.

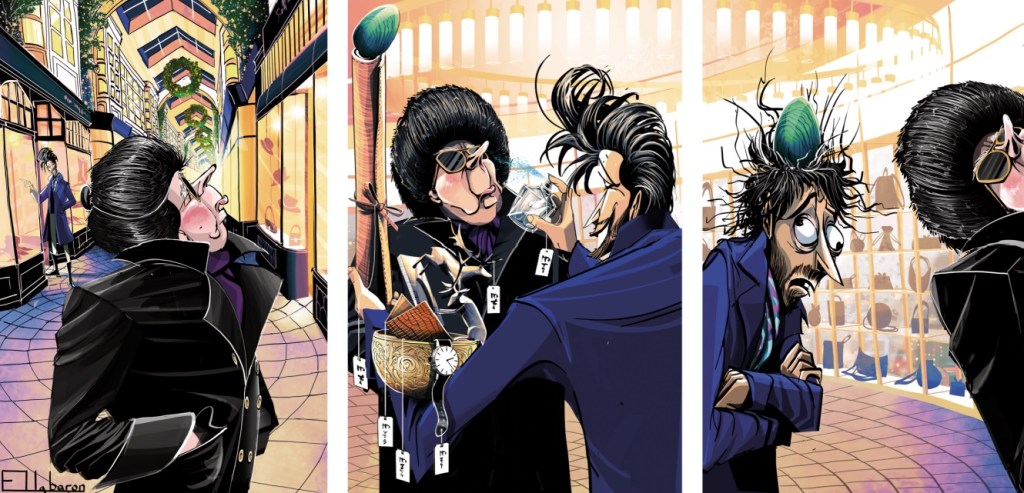

Andrew’s Rover was in the courtyard when I came down. He was sitting in the back wearing a Soviet-style fur hat and a rather splendid Ulster coat, with dark sunnies. “Strong look,” I said.

“I don’t suppose stylists have to be on time.”

“I am on time, Sir.”

“I meant early.”

We drove towards Haymarket. He asked me how I’d come to be living at Albany and I told him I’d recently taken it over from an oligarch’s son, who’d disappeared. “They say he may have been forcefully returned to Moscow, or killed.”

“Oh, yes,” he said. “I think I heard something about that.”

He seemed distracted by the Christmas lights. He wanted to know if I was professionally responsible for the “girlification” of Harry Styles.

“Not me, sadly,” I said. “That was Harry Lambert. Genius, I think.”

“My girls adore that sort of thing.”

We were stuck in traffic and he opened up about the trials of having to change one’s image, when image is everything. It was very funny, in a way, what with the hat and everything, but I nodded carefully.

“Is that a little Scouse smile on your face?” he asked, and I told him not to be silly. I take my job seriously.

“I want us to find the right thing,” I said. “I’ve been thinking.”

“Not a diamond watch. Nothing Bentley & Skinner.”

“Of course not.”

“Nothing Gucci.”

“No, I see that. But he’s a difficult man to buy for.”

“You’re telling me.”

I asked his driver to take us back up Piccadilly as I wanted His Highness to sniff something wonderful at Santa Maria Novella, the soap and perfume shop. “They’ve come up with the most perfect jasmine.”

“Certainly not,” he said. “The King only likes Eau Sauvage. That’s his scent. My mother was the same…”

“She liked Dior — Eau Sauvage?”

“No, stupid. L’ Heure Bleue. She wouldn’t use anything else.”

“One doesn’t use a perfume,” I said. “One wears it.”

“Oh, do be quiet,” he said.

*****

After two hours of driving around, tempers were becoming frayed, and I realized that what Andrew wanted was something very simple. We’d been to Burlington Arcade, where I had to prevent him from stopping for a shoeshine, and we entered a dozen little Mayfair shops, but it turned out he didn’t want a vintage watch or a golden bowl. He didn’t want a backgammon set of Moroccan leather, a jade egg, an alligator wallet or a silver inkwell shaped like a gang of elk.

“You want something mindful,” I said, returning to the car.

“If you insist. Ghastly word.”

“But something that conveys a little thoughtfulness.”

“Yes, I think so. This year, yes.”

So we decided between us to go to the National Portrait Gallery. For some reason he was really keen on that and had mentioned the gallery twice that afternoon. It was a risky venture at that time of day, but I told him I was a fan of the gift shop.

As the car pulled up into a cutting by St. Martin’s Lane, he unbuckled his seat belt and pointed to a John Lewis advertisement by the road. “Kindness is never wasted,” it said. “Live knowingly.” And with that we left the car and crossed the road. Something about the intrepid strides he was taking told me he was enjoying his day out. Nobody seemed to be looking. We could have sent a driver or a footman or a secretary to pick up a present, but he seemed to want the conversation, the journey, the irritation and the experience, just like everyone else.

“Let’s go up and see the rellies,” he said once we were inside the building.

We took the stairs to the third floor.

He hardly adjusted his costume, but very quickly it seemed tame among the busks, ruffs and farthingales of the Tudors. He moved through the gallery like he owned the place, which, in a manner of speaking, he probably does. In any event, ownership had become a bit of a theme with my friend and he was on a mission. I trailed in his wake, catching swatches of ermine and golden brocade, passing several of the first Elizabeth, a few of the Scottish Mary, plus a host of Cecils and Walsinghams, before we arrived near the back of the gallery where Andrew took off his sunglasses and spun round looking confused, right by a portrait of the family of Thomas More.

“Do you work here?” he said to a person wearing an NPG badge.

“Yes. Oh, goodness… Yes. I’m a Visitor Engagement Assistant.”

“Excellent!”

“Are you …?”

“Never mind that. Isn’t Cardinal Wolsey here?”

She seemed flustered. “Em. Yes. I mean, no. We do have a portrait, sir, by an unknown artist. But I’m afraid it’s not on display.”

He turned again to me. “It was very red, the painting.”

“Silks,” I said. “Cardinal red. Scarlet, really. Including the hat, perhaps the ‘galero,’ which was also silk and rather characteristic.”

“Do you ever stop?”

He turned to the gallery assistant. “He’s a pestilence on the dignity of the royal family,” he said, “and half my friends.”

“I’m sorry…”

The person seemed baffled.

“Oh, don’t worry. I’m only joking. He’s what they call a stylist.”

“An image architect,” I said.

Andrew burst out laughing. The assistant kindly told us that there were some photographs in the next gallery, not of Cardinal Wolsey but of actors playing him. A light came on in Andrew’s eyes. He charged through and we soon found ourselves in front of the photographs. “Sir Henry Irving as Cardinal Wolsey,” he read out, almost sneering at the display. He waved his hand. “This is what happens, you see. People are erased out of history. Their portraits are taken from the gallery. And people rely on rumors and fake stories for their information.”

I didn’t quite know what to say. I just nodded, noticing that Irving’s costume in the photogravure could have done with an iron.

“This is what happens,” he continued. “One ends up being played by actors.”

Coming down the stairs, he told me it was all in that novel I had given him, the first of those books about the Tudors by Hilary Mantel. He told me about a part early in the book where the king gives Wolsey a ring.

“I remember that,” I said. I was dreading what he was about to say.

“And Wolsey is struggling to think of something to give him back. And then he comes up with the ultimate gift. He gives him Patch, his favorite Fool.”

I stared back at him as we reached the ground floor.

“Fancy being a gift?” he said. “Fancy going to work for my brother at Clarence House?”

“Not really.”

“I’m sure he could do with an upgrade in the socks department.”

Cheeky fecker, as my mother would have said.

People in complex situations are often like little children when you let them roam. We made our way to the gift shop and Andrew was delighted by a series of trinkets. Christmas music was playing outside in Charing Cross Road and the day was fading, but twinkling lights gained the ascendant and he appeared to have reached the end of his problem. He called me over from the centre of the gift shop, where he beamed rather festively. “You were absolutely right,” he said. “This place is just the ticket. And I’ve found a good present, if you won’t be it.” He was holding up a pink, decorated package that said “Six Extravagant Paper Crowns. For Feasts, Parties, High Days & Holidays.” As I confirmed his decision I saw there was a little tightness about his smile. He tapped his pockets.

“Everything all right, Sir?”

“I don’t suppose you could spot me a 20?” he said.

Andrew O’Hagan’s novel Caledonian Road was published this year by Faber & Faber and was a Sunday Times of London bestseller. It was nominated for the Orwell Prize for Fiction, a Saltire Award and as Blackwell’s Book of the Year.

Leave a Reply