In the summer of 1955, an unusual meeting took place. Billy Graham visited the writer and academic C.S. Lewis in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalene College, Cambridge. It was unusual because leading British academics typically avoided Southern Baptist revivalists. But rather than encountering a fussy, prim don, Graham found a kind, intelligent scholar who was very happy to spend the afternoon with him. Later, Graham admitted he was intimidated by Lewis, but the English professor quickly dispelled any anxiety, probably by offering Graham a cup of tea.

Graham’s impact on American religious culture, for good or ill, is unquestioned, but it is difficult to imagine what that same culture would look like without the works of C.S. Lewis. While the preacher became “America’s Pastor,” the Oxbridge don became America’s professor, giving readers a sense of enchantment about their religious beliefs that was infused with equal doses of logic and reason.

Since Lewis’s death in November 1963, millions of people have found in his writings what Graham found in person: a scholar who makes it easy to forget he is scholarly. Lewis’s humane and commonsense approach to even the weightiest questions attracts readers from across the landscape of American religion, inviting even the greatest skeptics to sit and join the conversation.

Born into an Anglo-Irish family living in Belfast, the professor of medieval and Renaissance literature was an unconventional American favorite. Lewis was a late-Victorian romantic, educated in private schools and at Oxford. He was awkward and bookish, loving long walks, quiet pubs and late-night conversations about mythology and metaphysics over tea, tobacco and beer. A confirmed bachelor most of his life, he surprised everyone (not least himself) when he married the American writer Joy Davidman a few years before her death from cancer. Throughout his life, Lewis aspired to little more than having a good book to read, some close friends and a few creature comforts.

Nevertheless, by 1947, Lewis was on the cover of TIME, being compared to G.K. Chesterton and T.S. Eliot for works like The Abolition of Man and The Screwtape Letters. Since then, the American appetite for C.S. Lewis has only increased with time.

Many of Lewis’s books continue to garner a steady readership. Conferences, lectures, articles and books appear steadily to commemorate his life and works. The C.S. Lewis Institute, founded in 1976, boasts chapters in over fifteen American cities, and it was American investors who restored and maintain Lewis’s home “The Kilns” outside Oxford.

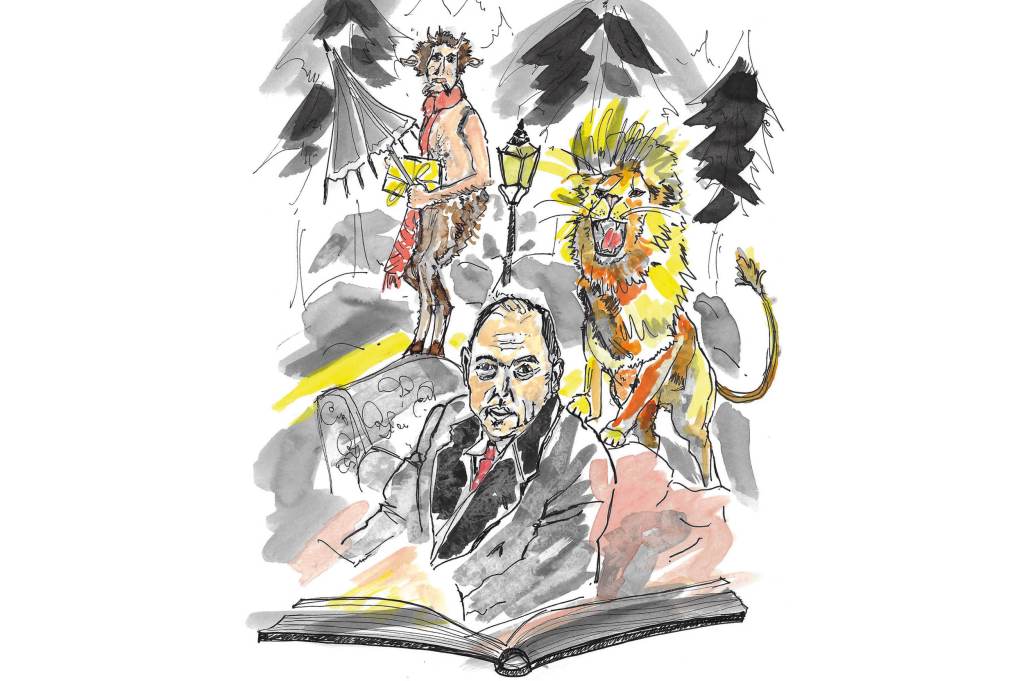

If TIME put Lewis on the cultural map, he became a household name in the US after the publication of The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–56). The fantasy novels about the Pevensie children and others stumbling into the magical kingdom of Narnia have sold millions of copies. Young and old readers are drawn into a world filled with talking animals, marsh-wiggles, phoenixes, dwarves, dragons, satyrs and unicorns. It is a place where wardrobes and barn doors are imbued with numinous power, time moves very slowly, humans dance with fauns and dryads, creatures can be turned to stone and potions heal wounds.

Adaptations of the Chronicles can be found in television, theater and film, and the novels have influenced bands like Deepspace5 and Evanescence as well as writers like Madeleine L’Engle, Lev Grossman, Leigh Bardugo, Neil Gaiman and J.K. Rowling. What is most interesting is the fact that the Chronicles are lightly veiled Christian allegory, which only seems to add to their appeal. As Adam Gopnik remarks in the New Yorker, “It is here that the atheist and the believer meet, exactly in the realm of made-up magic.”

It was Lewis’s appreciation for the power of stories that led him to explore Christianity in fantasy literature. As a young boy, Lewis enjoyed getting lost in stories, particularly the ancient Norse myths. Stories, he believed, allow us to be more than ourselves, to “see through [the eyes] of others,” offering not only an escape but an alternative experience of reality.

Narnia’s deepest magic is perhaps the alternate reality it fashioned for Christians about their own religion. Lewis’s biographer Alister McGrath notes that Lewis is “that rarest of phenomena — a modern Christian writer regarded with respect and affection by Christians of all traditions.” This affection springs from the way that Lewis restored a sense of story and myth to Christian theology. Lewis once described Christianity as “a myth which is also a fact,” and in Narnia, he recreates the mythology in a way that most brands of Christianity find endlessly delightful. Phrases like “he is not a tame lion” and “further up and further in” have become theological truisms for many readers. A particular fan favorite is Lewis’s description of Narnia under the curse of the White Witch as a place where it is “always winter but never Christmas.”

Even Christians who normally shun stories about magic cannot resist Narnia’s allure. As historian Mark Noll points out, fundamentalists and evangelicals were the last groups to join the Lewis reading party, but their reticence did not last long. Narnia pulled these normally separatist-leaning groups into the mainstream of American literary culture, sparking an enthusiasm for Lewis among evangelicals that is unmatched in most other Christian traditions.

Part of Lewis’s broad appeal can be found in his persuasive, charming and informal style. In his works of Christian apologetics, Lewis writes like a well-read everyman who is seeking truth, inviting readers along for the ride. His bestseller Mere Christianity communicates through imagery and analogy more than sheer rationality and evidence. Lewis the storyteller is never far from the surface; his readers are presented a version of Christianity described in terms of statues coming to life, human telescopes, divine rebellion and life-long journeys.

Another aspect of Lewis’s appeal is what the late Presbyterian pastor Tim Keller described as Lewis’s “unusually wise” way of dealing with challenging questions. Because Lewis is accessible, his logic can strike a reader like a thunderclap from a cloudless sky. This is particularly true when considering matters of the human condition. For example, in The Weight of Glory, Lewis wrote, “We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us… We are far too easily pleased.” There is a self-effacing quality to this sort of wisdom that is at once disarming and at the same time difficult to accept without challenge.

It is, however, Lewis’s celebration of what he called “good reading” that has likely had the greatest impact on American culture. From Narnia and his apologetics to his scholarly writing on English literature, all of his works arose from a well of joyous reading that seems at times inexhaustible. Lewis read widely and constantly, even suggesting in Surprised by Joy that “eating and reading are two pleasures that combine admirably.”

Lewis’s good reading has captured the imagination of the burgeoning classical education movement with hundreds of schools across the country that emphasize the reading of the western canon. The founder of the Association of Classical and Christian Schools, Doug Wilson, refers to himself as “a C.S. Lewis junkie,” and in such circles, one need only drop Lewis’s name in conversation to see ears perk and eyes light up. In Lewis’s books An Experiment in Criticism and The Discarded Image, classical schools find a champion who assaults things like literary criticism, which spends time “judging books” rather than enjoying them, and progressive assumptions about the past while celebrating the Great Books tradition.

Equally appealing to the classical school movement is the fact that Lewis styled himself a conservative thinker, even a “dinosaur,” who viewed the world through a pre-modern lens. Lewis’s type of conservatism predates the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution by a few centuries. He warned against overconfidence in human reason and distrusted technology, and he was convinced that reality transcends sense experience, explaining, “You have never seen more than an appearance of anything.”

At the same time, these eccentricities are perhaps why there are not too many “Lewisites” in America. Lewis is a commonsense thinker, but it is a commonsense from a past age. While he has millions of admiring readers, few are determined followers. Instead, Lewis’s influence on America has been manifested in different, and at times disparate, images. He is the myth-maker, the scholar, the convert, the defender of the faith, the rebel, the writer and the teacher.

Like a beloved professor who is slightly out-of-step with everyone else, Lewis inspires readers, opening up possibilities and ways of thinking that we would never see on our own. Part of his charm is that Lewis does not insist that you agree with him in order to enjoy his company. His intelligence and learning are clothed in an affability and warmth that sets the most virulent critic — or a nervous evangelist — wholly at ease.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2023 World edition.

Leave a Reply