Alex Kaplo lives, apparently, the life of Riley. The thirty-one-year-old’s website shows him roaring around in a Mercedes, and he boasts of taking “extravagant” vacations and living in a high-end apartment. He has made all his money, as it turns out, as a “publishing chief executive.” He has caused hundreds of books to be released, none of which he has written.

His story appears, alongside a few others, in a report in the Sunday Times of London about the people who are really getting rich from publishing these days. And, spoiler alert: it isn’t traditional publishers, still less (ha ha) actual authors. It is a new breed of entrepreneur who scours Amazon for popular search terms, identifies undersupplied gaps in the market, and commissions ghostwriters — or, in some cases, AI — to fill them fast and fill them cheap.

Amazon’s direct-to-kindle publishing and print-on-demand facilities mean that anyone, now, can set up as a publisher. And with margins of between 35 and 70 percent for authors who self-publish directly through Amazon (which can, it seems, include those with the nous to commission a ghostwritten text for a flat fee), even a modest sale can be profitable. As Mr. Kaplo says, “You’re hiring a writer to write the book for you and you will claim all the rights to the book, including all future royalties. You own the license, they own nothing.”

As someone who has just spent a year and a half researching and writing one of those old-fashioned, grass-fed, hand-reared books, and nearly lost my sanity in the process, I hope readers will indulge me in registering a reaction to this. The reaction is: aggrieved.

People like me cling to the idea there’s something irreducibly valuable and distinctive about human creativity

Of course, most writers know that there’s no money in books. They know that you are better off, time-to-money-wise, deploying your modest facility with coordinating conjunctions writing, I dunno, press-releases for large corporations, or greetings card slogans, or the instruction manuals for washing machines. But there’s a certain, perhaps nostalgic, point of pride in the idea that this is something worth doing.

And yet, I look at this instinctive reaction, and I slow down, and I think: what do I have to object to? Isn’t looking for gaps in the market what normal publishers do, and have always done? Isn’t slapping a pseudonym on a piece of ghostwritten text what publishers often do, and have always done? There’s a bit more of an imposture on the public, you could argue, if a book purporting to be by Millie Bobby Brown (to pluck an example from the air) turns out to be the work of somebody else entirely than if the work of one author you’ve never heard of turns out to be the work of another author you’ve never heard of.

Is it not just snobbery, this sense that there’s something a bit off in the way that random herberts with no publishing experience, and who have never rummaged a slush-pile or taken a dandruffy old literary editor for a long lunch, can make a bunch of dough out of selling books? From one point of view, books are sacred pinnacles of the culture. But from another, and you can bet it’s the one from which most publishers operate, they are what most of them have always been, which is to say, products that members of the public buy for a price they’ll tolerate in the hopes of being edified or, more often, entertained.

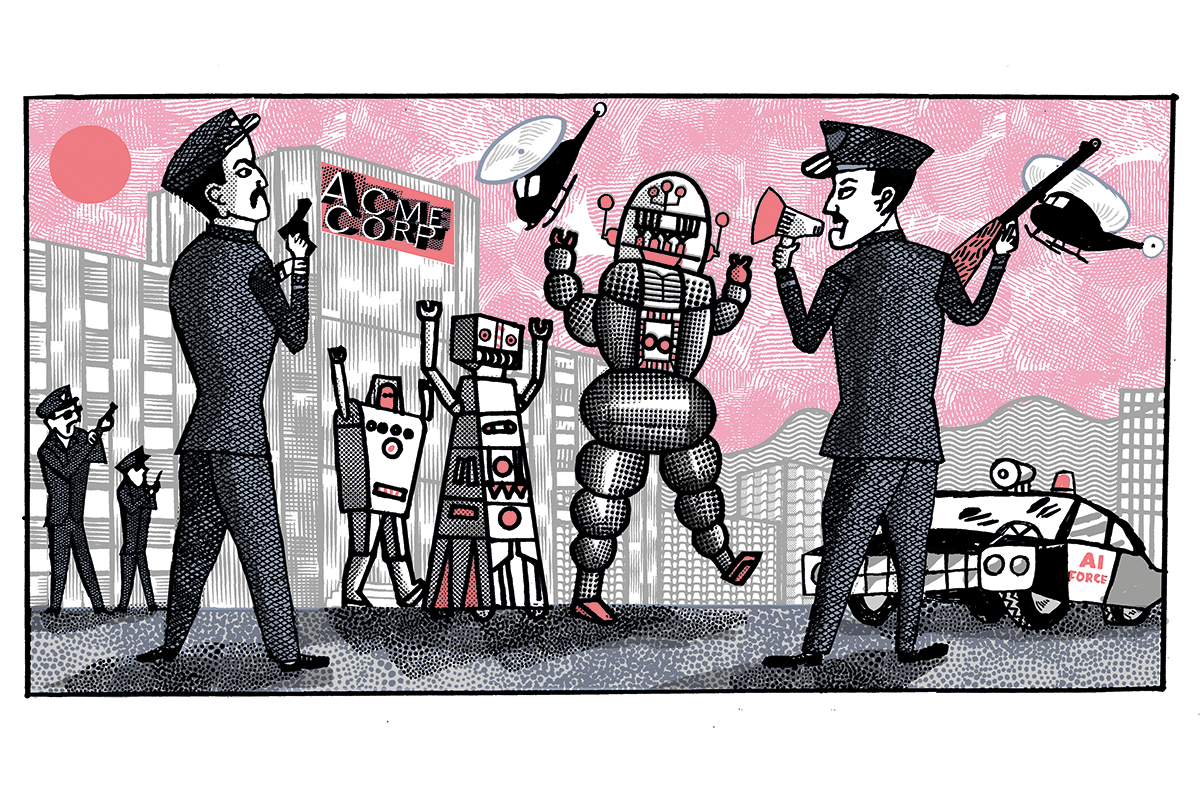

Amazon’s technology simply means that, rather than needing to arrange printing, warehousing, marketing, design, distribution and all the other things that have traditionally presented a high bar to entry for publishers — that have made publishers gatekeepers of a sort — any fool can do it for the price of an hour or two on a laptop. Why shouldn’t they?

These ghostwriters are clearly to some extent being exploited if they’re signing over their work for a flat fee rather than taking a royalty. If, as is reported, there are people in online marketplaces offering to write a romance novel for $100, those people are selling their work too cheap. But in both those cases, caveat vendor. There’s nothing to stop any of them demanding a royalty, or setting up as publishers themselves. They have something these “author/publisher” entrepreneurs haven’t: they can write. That’s the tricky bit, after all. What’s to stop them recognizing what Mr. Kaplo and his peers are doing and doing it for themselves? It costs nothing, after all, to publish through Amazon. Shades, here, of the early days of the comics industry, when the publishers grabbed all the intellectual property and the writers and artists were paid piecework, by the page. Eventually those writers and artists got wise, and the balance of power shifted.

And if the books are being generated by ChatGPT, well. People like me cling to the idea that there’s something recognizably and irreducibly valuable and distinctive about human creativity. And I think, so far, we’re probably right. But it’s a fool who remains complacent about the matter. I already know a number of people, some of them professional writers, whose work doesn’t stand up all that well against ChatGPT. And the AI is getting better all the time. I daresay Don DeLillo and Kazuo Ishiguro don’t have that much to worry about in their own lifetimes, but it doesn’t seem at all implausible that in a decade or two AI will be able to knock you out a perfectly readable gardening manual, self-help book or even a spy thriller.

We may, still, bridle at this. Indeed, we may think that Amazon would do us all a favor by making clear to buyers which of the books in the Kindle store have been written by computers and which have been written by humans, on the analogy of supermarket labeling. But we all know that “handmade,” “home-cooked” and even “organic” on a packaged pudding can cover a wide range of possibilities; the difference between a text generated by AI, a text whose story was suggested by AI, a text edited by AI, or a text spellchecked by AI, will tend to get pretty blurry. And as with the supermarket, the proof will be in the pudding. It’s dismaying that the balance of shoddy stuff to quality work on Amazon is likely to tilt towards the former (hilariously, Amazon aims to counter this by restricting people to self-publishing three books a day), but that’s the way of the world. Why should books be any different in this respect from clothes or gifts or electronic tat?

And the readers? Well, I daresay a lot of them are spending a few cents on some hastily written and disappointing books, and they may come to regret that. You can do the same, mind you, in any high-street bookshop. What was that saying about a fool and his money?

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply