Whitney museum: no space for profiteers of state violence // dismantle patriarchy // warren kanders must go! // supreme injustice must end // we will not forget // choking freedom is a crime // enough // greed is deadly // humanity has no borders // we grieve the harm…

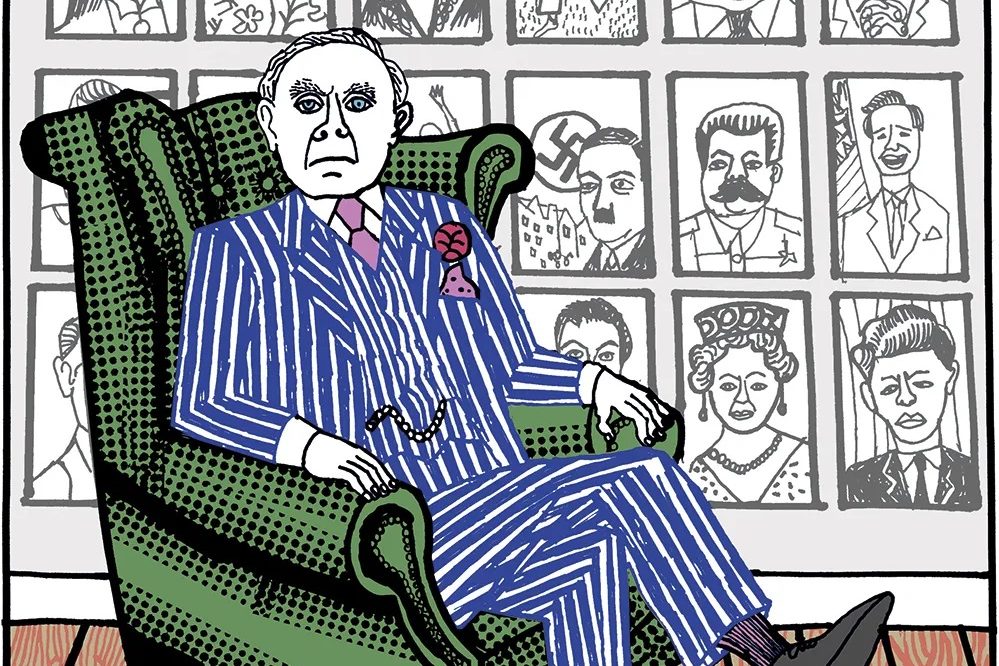

If that array of posters paving the entrance to New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art hasn’t plunged you into such an insensate catatonia that the print has blurred, here’s the drill. For months protesters have been campaigning to have Warren B. Kanders, the museum’s vice chairman, who’s already donated $10 million to the institution, removed from the board. Eight artists withdrew from the Whitney’s esteemed Biennial exhibition in solidarity. Last week, with more than a suggestion that he didn’t jump but was pushed, Kanders finally, and stiffly, resigned — presumably taking his fortune and any future donations with him.

Kanders’s crime is to own Safariland, a company that manufactures law-enforcement supplies, including tear gas that may have been used on migrants trying to storm the US-Mexico border. Since enforcing your own immigration laws is tantamount to genocide in certain American quarters, that makes Kanders’s money and service tainted. Similarly, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art will no longer accept contributions from the Sacklers, owing to the family’s association with the manufacture of the addictive opioid OxyContin.

Let’s do a reality check. Now that Warren Kanders has stepped down as a Whitney trustee, exactly how many individuals among those huddled masses yearning to breathe free on America’s southern border will not be subject to tear gas? Or now that the Met is shunning Sackler funds, the victims of America’s opioid crisis have been reduced by exactly how many addicts?

None, you say? Seriously? Not, in either instance, even one? Gosh, I’m bewildered. Then what was the point?

You have to admit that it’s a curious version of chastisement: refusing to let people give you their money. I only wish more charity workers spieling interminably at my front door would punish my dubious politics in this fashion.

Insofar as there is one, the logic seems to run that we are doing evil corporations an enormous favor by allowing them to part with their cash and thereby attach to prestigious cultural brands. By accepting donations from politically unclean sources, museums are participating in moral money laundering. Because what we all need more than anything is still more collusive, self-congratulatory lefty jargon, we therefore have the on-trend gerund ‘artwashing’ — which does not refer, alas, to refurbishing Old Masters.

The same pressure for fiscal spotlessness is being applied to the British Museum, which has thus far resisted the clamor to jettison the sponsorship of climate monster BP. (The resignation of Sir Mark Rylance from the Royal Shakespeare Company in June over the theatre’s acceptance of BP’s tarnished 30 pieces of silver has no doubt vastly reduced worldwide dependence on fossil fuels.) The campaign group BP or Not BP? has decried the petroleum giant’s support for British cultural institutions as letting the company appear as a ‘good corporate citizen’ and conveying a ‘veneer of respectability’.

It’s not a very good novel, but the title of Jonathan Franzen’s last doorstop at least captured the contemporary zeitgeist: Purity — which is more a spiritual goal than a practical one. Seeking a state of immaculacy entails sanitizing the soul, and little concerns what actually happens. Moreover, the list of products, places, and economic sectors linked in the left-wing mind with moral corruption is long and growing: meat, plastic, armaments, pesticides, airplanes, cars, banks, fast food, sugar, Israel, GM crops… Should they spurn all prospective contaminations, our cultural institutions could soon be beyond reproach, and broke.

Ethical investing probably doesn’t make much more difference to the real world than that fresh-from-the-shower feeling administrators must now be having over at the Whitney. Someone else is liable to purchase the shares that squeaky-clean investors regard as defiling. But there’s at least a nominal sense to withholding your own monies from companies that sell products of which you disapprove, even if you may make a negligible difference to the here and now. Yet there is no logic to refusing to take these suspect companies’ own money away from them.

It’s worth asking what Warren Kanders, the Sackler family and BP execs are going to do with the philanthropic funds that we no longer want to permit them to give away. Buy a better grade of champagne for staff picnics? Or a new company jet? Now, that’s really making the world a better place.

All money is dirty. My mother always warned me not to touch my mouth or nose after handling cash: ‘You don’t know where it’s been.’ Any money has constantly changed hands. Given the errant proclivities of the human race, some of those hands undoubtedly stank. What matters more about money than where it came from is what you do with the stuff once you get your mitts on it.

This museum ballyhoo is all about posturing. I grew up deeply suspicious of altruism, because I was raised around so many churchy people who fancied themselves altruists. Even as a kid, I could tell the difference between wanting to do good and wanting to be thought of as doing good, because virtue and vanity are chalk and cheese. I don’t know the guy, but I’ve little doubt that Warren Kanders had his own reasons for serving on that museum board. Maybe he liked swelling at the galas, being sucked up to as a rich donor, and being thought of as doing good. By sheer accident or coincidence, maybe he also did some good — but he won’t do good at the Whitney any more.

Often equally obsessed with, say, tearing down statuary that nobody looks at anyway, many of today’s firebrands don’t seem to care whether their ‘activism’ produces real, tangible benefits. After all, if you’re running an institution that aspires to preserve and display enduringly important artwork, and some dodgy character offers your museum a packet, you’re being given a chance to convert ill-gotten gains into a force for benevolence. So, obviously! Take the money and run.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.