Ancient Greek thinkers tried to explain every natural phenomenon in human terms, without reference to magic or gods. That was a major intellectual revolution. Greek doctors’ contribution was to invent what has been called “rational” medicine, embedding a principle of the highest importance, however hopeless its premise: which was that the health of the human body depended on the proper mixture inside it of four “elements:” earth, air, fire (i.e. heat) and water and their associated properties (heat, cold, wetness, dryness and so on).

Further, since dissection was mostly forbidden, they knew little about how the body actually worked (they did not know what the heart was for). But because Aristotle (incomprehensibly) supported the whole package — and though doctors like Hippocrates (fifth century BC) and Galen (third century AD) made many brilliant observations — the Greek theory of disease, embraced, with caveats, by the Romans, remained at the heart of much medicine until the early nineteenth century, when powerful microscopes allowed doctors for the first time ever actually to see and so discriminate between healthy and diseased cells, enabling real cures.

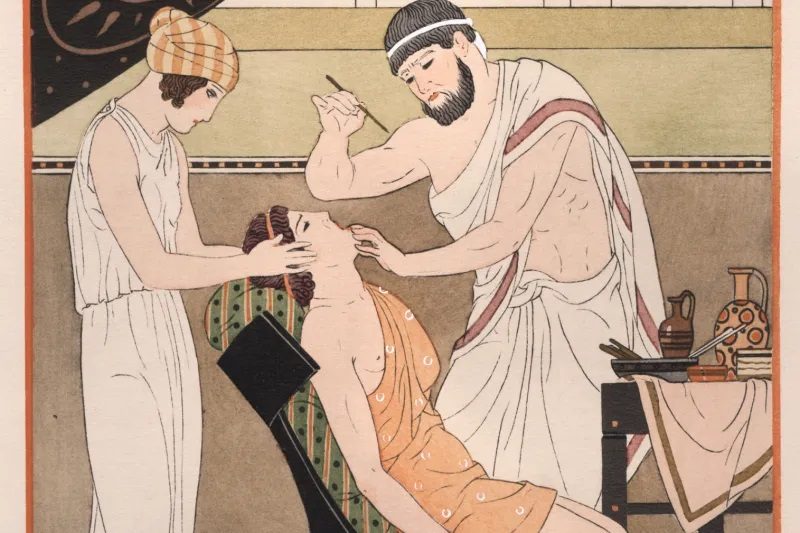

But at least for visible problems, doctors had practical solutions. This is how they dealt with hemorrhoids: “Have the person lie on his back and place a pillow under the lower part of it. Force the anus out as far as you can with the fingers, heat up the irons till they glow and burn the hemorrhoids until you dry them off completely. Leave nothing uncauterized… your assistants must hold the man down by his head and arms so that he stays still, but otherwise let him scream during the process, since that makes the anus stick out more.” Very probably.

So what did patients, at least those who had access to a doctor (rare in rural areas) make of it all? Aesop’s Fables offer an invaluable insight into popular beliefs and one of them goes like this: a doctor asked a sick man how he was getting on, and he replied that he was sweating heavily. “That’s good,” said the doctor. Next time the doctor went round to ask how he was feeling, the patient replied: “Shivering rather a lot.” “That’s good too,” the doctor said. The next time the man replied: “I’ve got diarrhea.” “That’s good as well,” said the doctor. Then one of his parents came to find out how he was. “Dying of good symptoms,” he replied.

That doctor was doing his best: visiting regularly, being optimistic, and tracking the course of the patient’s illness (“prognosis”) to see if it matched anything he had already met. That is impressive — it is a vital procedure in modern medicine — but given the four-element theory, it would have achieved nothing. No wonder doctors, to save their own reputations, often abandoned the terminally ill. Ironically, it was the educated wealthy, keen to follow the latest “science,” who used them most.

Given the cures on offer (some involving e.g. human and animal excrement), they would almost certainly have been better off leaving nature to work its magic. To that extent the poor were luckier. In the world in which they lived, fancy doctors were suspect anyway, and there were many other options with much longer pedigrees — plant cures, dream cures, preventative amulets (especially for children), and oracles. Turning to all-powerful gods for a miracle cure was very popular (Asclepius, who provided sleeping cures in his temples, was thought to be especially kindly to humans), and Jesus’s example gave a tremendous boost to the claims of Christianity. But doctors dismissed such stuff and saw no reason to engage with it.

There was also a long history of families relying on their experience. Cato the Elder, for example, recommended cabbage as the ultimate cure-all for everything from cancer, ulcers and urinary problems to a dislocation. Why not? Cato lived to be a very old man. It had worked for him. That must have been good enough for your man in the street. This takes us all the way back to the fifth century BC Greek historian Herodotus, who tells us that Babylonians had no doctors, but that anyone who fell ill was immediately taken on to the street and left there. Everyone who passed by had to ask what the trouble was and “suggest remedies which he has himself proved successful in whatever the trouble may be, or which he has known to succeed with other people.”

Community in action! Self-help! The perfect health solution!