When Max Ernst was asked by an American artist to define surrealism at a New York gathering of exiles in the early 1940s, he pointed across the room at André Breton and said: “That is surrealism.” Even today it can seem as if no other answer is available, so tenacious was his grip. A former student of neurology and psychiatry, with no qualifications other than an instinct for the coming thing (“an astute detector of the unwonted in all its forms,” as he later described his fellow conspirator Louis Aragon), Breton encountered the early writings of Freud as a medical orderly on a trauma ward, during the World War One, and immediately recognized the significance of his work.

Surrealism was in the first place a delayed response to how ordinary life had been exploded by the carnage of 1914-18. The dadaists prepared the ground with their charge that rationality itself had led the drift to war and was no longer to be trusted, but ridiculed and subverted. Compelled to repeat the trauma, in their performative fashion, dada demanded reparations in the coin of the irrational: the right to transgress in perpetuity. To which surrealism added its constructive twist, and Breton’s almost mystical sense of the group as a vital source of intelligence.

The surrealists wanted to put us to sleep in order to wake us up

The movement, kickstarted by the Surrealist Manifesto, which was published 100 years ago this month, gave us a new world — literary, visual, photographic, filmic — and a new word, which has been used and abused ever since. “Surrealism” is hard to take stock of because it had to cross so many boundaries to say what it meant: art, philosophy, linguistics, psychoanalysis, politics, ethnology, science, magic…

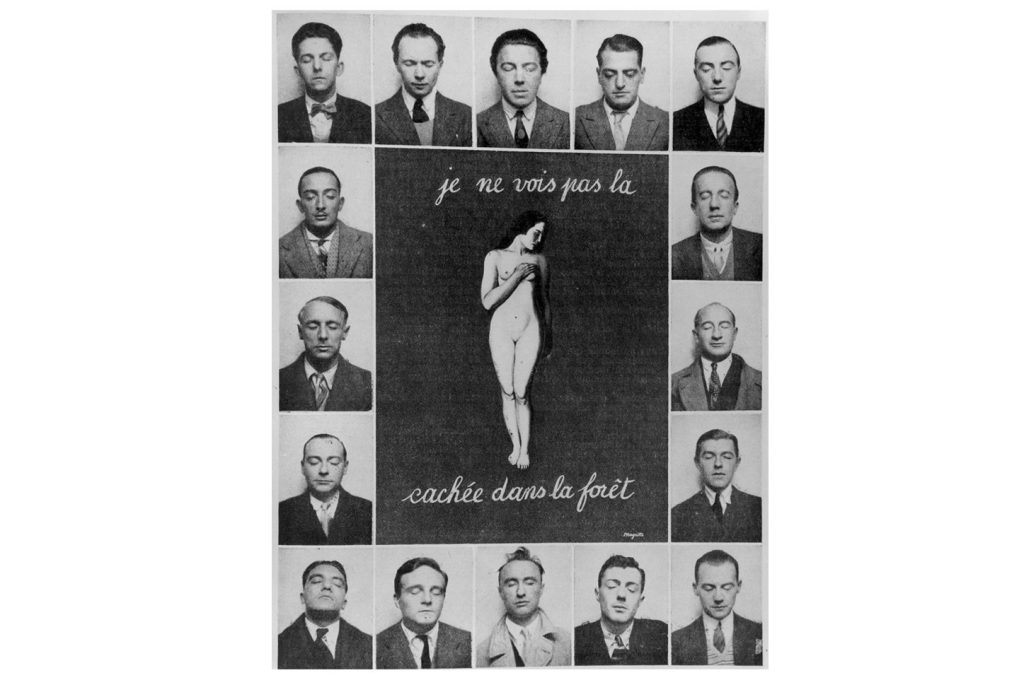

Breton had a sheepdog-trials zest for rounding people up and telling them where to stand. He took over naturally or mysteriously from Apollinaire (after the latter’s early death in 1918) as the spokesman for a Parisian avant-garde, whose cosmopolitan ranks were swelling. The dadaists Picabia and Tzara arrived from Zürich in 1919 and 1920, Miro from Barcelona in 1920, Man Ray from New York (1921), Ernst from Cologne (1922), Hans Arp from Strasbourg (1925), Dalí from Madrid (1926), Magritte from Brussels (1927) — a full flush of proto-surrealists, of whom only Aragon and Yves Tanguy were true-born Parisians. Walter Benjamin, writing in 1929, described the movement as “the last snapshot of the European intelligentsia” — and no group ever loved posing for the camera as much, often with eyes closed. The Manifesto codified surrealism as a vision of life, open to whatever lies beyond human agency. A new art was needed, verbal and visual, “free from all control by reason, exempt from all aesthetic or moral preoccupation.”

The term “surrealism” was first used by Apollinaire in 1917 (as an improvement on “supernaturalism”) to describe Cocteau and Satie’s ballet Parade. But its second outing was courtesy of Breton and his early comrade Philippe Soupault, with whom he had collaborated in 1919 on The Magnetic Fields, a headlong exercise in “automatist” procedures, or pure expression, on the page, and they named this new activity “surrealism.” Uncontrol was in the first place an event in language, not unlike the new kinds of listening outlined by Freud to define the analytic encounter: a form of free-floating attention or unconscious communication.

In senses now difficult to recover, surrealism was not, at the outset, an art movement with an aesthetic, and Breton at one point referred to painting as a “lamentable expedient.” Rather it harnessed and repurposed dada’s intransigence (anti-art, anti-craft, anti-easel, anti-humanist). The means were artistic and diverse, but the ends were other: to refashion human understanding “from top to bottom” and transform the mindset of everyday life — to make us aware of the Truman Show that is ordinary reality. The surrealists wanted to put us to sleep in order to wake us up — to free the subject from false rationality and restrictive templates. It is a style of thought, in the first place. The idea being that if you transform the imagination, the rest will follow. (Outsiders often felt there was something “fundamentally black-magicky” about all this, in the words of Mina Loy, and Freud regarded them as a bunch of cranks.)

The classic objects and images of surrealism have shock in common, or what Breton called “le saccade” (a jolt), and they seem to shock each other rather than share an iconography: a melting watch in a desert landscape; a lobster telephone; sugar lumps made of marble; a cup and saucer covered in fur; Man Ray’s close-ups; Ernst’s eerily controlled yet oneiric procedures: mineral and archaic scenarios alive with eyes, mosses, insects and encrusted hybrid figures; or the wriggling biomorphic communities which dance through Miro’s serene canvases and the precisely seen organicist wreckage of Tanguy.

But we know a surrealist image when we see one, their hidden premises are legible — we file them effortlessly in the same mental drawer, which suggests that reality has indeed re-arranged itself around the surrealist dream of an alternative order. It is also true that the movement never surrendered its connection to realism. “Surreal,” we say, meaning (in one of its senses) a step away: holding up a cracked mirror to what is there, rather than freely imagining an elsewhere. (In this sense surrealism has little to do with utopias, or utopian thinking.)

The interest in primitive arts was a reaction to the horrors of civilized behavior in World War One

In Wittgenstein’s words, “problems are solved not by new information, but by rearranging what we have always known,” and Magritte’s paintings showed common things in unthinkable arrangements: a steam locomotive emerging from a marble fireplace into an empty room, a blue sky filled with a grid of identical floating men in overcoats and bowler hats looking like rain, a full length portrait of a man whose face is hidden by a large green apple — images the more disturbing for being so diligently rendered. The realistic has become the enemy of the real.

Breton invoked The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) as a foundation for the renovation of art and its capacity to convey buried meanings. But Freud was concerned to excavate the psychic origins which govern individual destiny — the dream has a hidden explanatory force for the dreamer. Surrealism, on the other hand, was fascinated by how the dream loosens individuality, and by the dream as a work of art which creates itself (a recurrent surrealist fantasy and more recently a widespread AI fantasy), offering a duplicate world, rather like photography. Giorgio de Chirico — whose painted enigmas (first seen in Paris in 1911) kickstarted the visual imagination of surrealism — went so far as to suggest that “no dream image, however strange, strikes us with metaphysical force. Far more inexplicable is the mystery and aspect our minds confer on certain objects and aspects of waking life.” This strikes the surrealist note, with its extroversion and urge to legislate for collective as much as individual experience.

The first surrealists were interested in the unconscious as it erupts into the light of common day, which meant the city as much as the psyche. Thus the quest motif that informs so much of their thinking and behavior, the pilgrimages and wanderings, the allegiance to chance and its dictates. Breton’s autobiographical novel Nadja (1928) imagines the unconscious as a street. The heroine of its title is a passer-by, a spontaneous surrealist pursued by obscure promptings, a follower who is in turn followed, led on by the collage of coincidence that is the city.

The street included the suggestive power of certain objects, randomly encountered. The Parisian flea markets were a favored site, where free-floating attention encountered things with nowhere to go, stripped of context, “old-fashioned, broken, useless, almost incomprehensible.” This passion for material culture was continuous with the interest in the dream as the key to the riddles presented by the observable world, the aleatory and enigmatic “evidences” present everywhere around us.

Modernity is a salvage operation, and surrealism often has an air of looking backwards. With Rimbaud in mind, the word “hallucination” would have defined most closely their aims and expectations. They were conscious of excavating what existed already but had no name — rather as Freud had to coin his own lexicon of new words for old psychic realities. There was an odd reassurance in the fact that these things had remained nameless — too close to be seen clearly.

In this sense there was no rupture between before and after the war. One reason they needed the past, the pre-surreal order, was that if a hidden continent existed inside the ordinary it must have been there all along, and prior art must be full of confirmatory traces. Moreover so many retroactive forces are involved. There is no way of telling what may yet become part of history. Benjamin praised Breton for grasping the revolutionary energies of the outmoded: “the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photographs, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has started to ebb away from them…”

A section of Aragon’s 1926 novel Paysan de Paris is set in the about-to-be demolished Passage de l’Opéra, one of the ubiquitous Parisian covered corridors, “human aquariums” with their glaucous light, at once indoors and outdoors, the city in a bottle, all cast iron and glass. Aragon itemises the contents of this microcosm as a dream-order of redundant things — its shops and small trades, its façades and erotic possibilities, where the tread of a stranger is closer to us than our own thoughts.

The old Trocadéro museum of ethnography (which closed in 1935) was another privileged site of the surreal — an unlit and unheated remnant of the 1878 World’s Fair, long fallen into disuse — whose arrangements did not spell disorder so much as another dispensation. Opposition to the French colonial war in Morocco in 1925 was the founding political gesture of surrealism, and the movement was intricately bound up with the explosion of French ethnography in the 1920s.

The interest in the primitive arts (of Oceania, especially), was a reaction to the horrors of civilized behavior exemplified by World War One, but also a curiosity about the survival into the present of societies where art has functions (symbolic, ritual) other than aesthetic, and whose objects or fetishes are also tools, integrated into ordinary life. Breton and Ernst were avid collectors of artifacts, on the lookout for the anonymous masterpiece.

At times, surrealist researchers (they were deeply and paradoxically vested in study and documentation) threw up the question as to whether more works of art are needed: how to interrogate art without merely adding to the existing excess. Anchored in states of mind, surrealism could sometimes seem like a religion of faith rather than of works, its broader purpose “to create a movement in the mind,” rather than to change material conditions or the physical order of things. In some respects it was a hypothetical affair, and its acolytes were peripatetic wanderers rather than men (mostly) with art careers. Direct action was never the movement’s strong suit, and what Sartre referred to as surrealist “quietism” left the world magically unchanged after its passage. As Magritte remarked: “I think we are responsible for the universe, but this does not mean that we decide anything.”

This is why the politics of surrealism — and its early choice of the French Communist Party as unwilling bride — were so hazardous and inconclusive. When push came to shove, the subjugation of art and anarchy to the revolutionary cause was unpalatable for Breton, who had a genius for inconsistency. In one self-consuming formula he declared surrealism to be in favor of “the independence of art — for the revolution; The revolution — for the complete liberation of art.”

Hollywood adapted its methods with hypnotic fluency — starting with Dalí’s dream-sequence in Spellbound

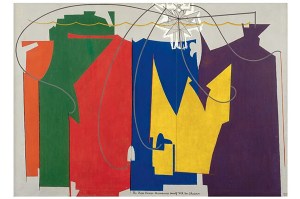

The afterlives of surrealism begin in New York. When the surrealists washed up there in the early 1940s, their work had preceded them, notably in a big exhibition at Museum of Modern Art in 1936. They kept themselves apart, like a lost tribe, but their presence was momentous and it is curious that surrealism, with its referential relation to the outside world and intermittent hostility to abstraction, could have so influenced advanced art in America. But painters such as Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock found richly intuitive ways of exploring the principles of automatism for abstract expressionist ends. At the other end of the spectrum, pop art found ironic uses for the surrealist object-world, and the movement’s hybridizing of high and low enabled the soup cans and dream furniture of pop (just as the shamanic posturings of Dalí indirectly licensed the antics of a showman like Jeff Koons).

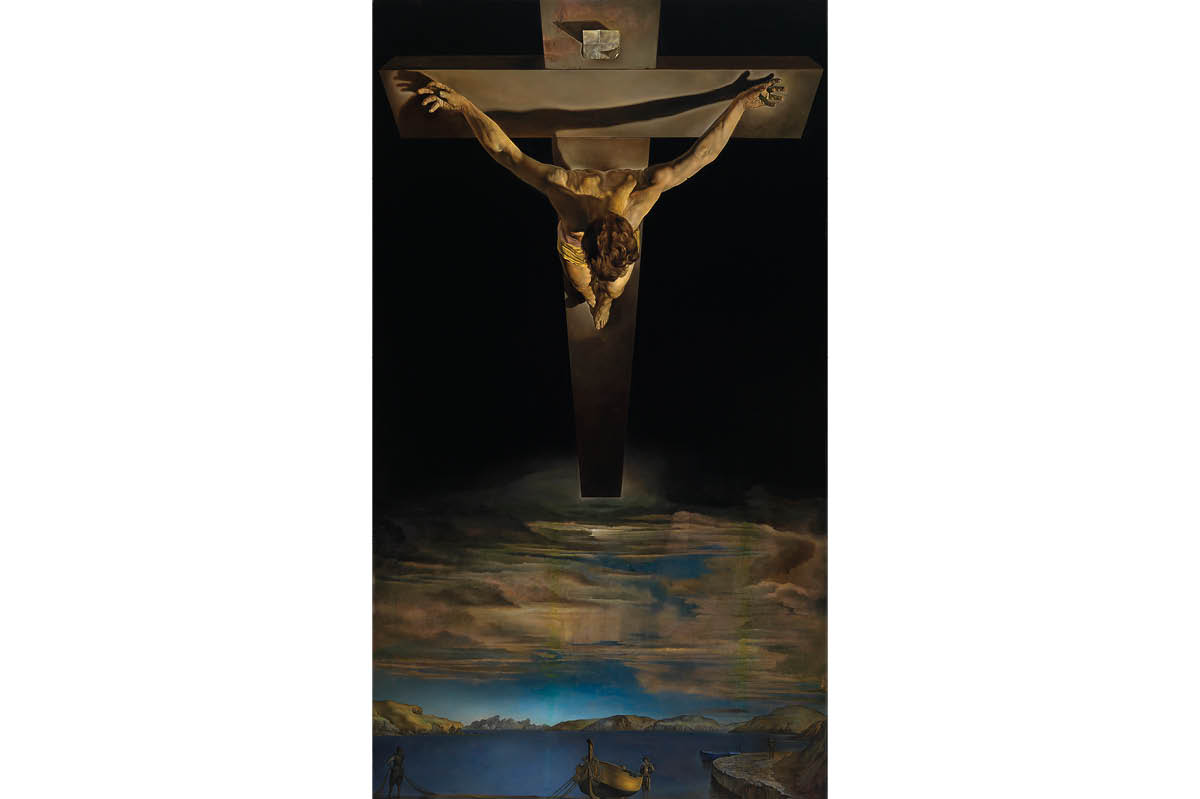

Part of the reason why the movement endured was its ability to penetrate contexts deeply inimical to its principles. If it seems dateless, rather than alive or dead, this is because of the ubiquity of its meanings, from which we establish a safe distance only with difficulty. We need the word, as part of the small change of modernity. In this sense surrealism ended when it began to flourish as a brand, a figure of speech, part of the image-repertoire. Having topped and tailed psychoanalysis, surrealism was in turn asset-stripped by advertising, which channeled its flair for the instinctual into the science of subliminal suggestion and the arts of persuasion. American cinema adopted its associative methods with hypnotic fluency — starting with the dream-sequence provided by Dalí for Hitchcock’s Spellbound — but the analogies lack conviction: Hollywood stays wide-awake, while it is we who do the sleeping.

AI image-generation too seeks to pass itself off as a creative heir to surrealism, but the outcomes of image-generation are merely the products of a different form of rationality. The machine dreams of AI depend on the market forces that produce them, and programs with names like DeepDream® proffer an idea of the unconscious that is all too conscious. The word “proprietary” had no place in the surrealist lexicon, and if the surrealists were alert to the eventuality that desire would lose its capacity to disrupt, AI is what they might have had in mind.

The surrealists desired to be “unacknowledged legislators” (as Shelley defined the poet in 1821, a hundred years earlier). And it survives as a mood, or rather an imperative mood, a form of bossiness. You must change your life, was Breton’s essential demand. It also survives as a certain kind of image: momentary, implosive and non-negotiable. The most memorable of the street slogans from the Paris protests of 1968 was “Sous les Pavés la Plage” (“beneath the pavement the beach”), referring to the sand on which the cobbles repose, with a filial nod to the barricades of 1848. It spoke for unconscious life, beneath the mineral city — not unlike Rimbaud’s compressed vision of “a drawing room at the bottom of a lake,” which surrealism adopted as one of its earliest talismans.

The image also looked back to dada and its sense of purposelessness, which was the lifeblood of surrealism. For both movements, everyday life was the theater of play and the condition of possibility. The surreal is contained inside the real, which is where the movement’s belief in the unfettered imagination still plays out, as an intuition that is alive a hundred years on.

Surréalisme is at the Pompidou Center, Paris, until January 13, 2025. Forbidden Territories: 100 Years of Surreal Landscapes is at the Hepworth Wakefield from November 21 until April 27, 2025.