One thousand days into Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, three facts seem to be evident. First, Russia is losing. It is using its soldiers like human ammunition, burning through its economic reserves and mortgaging its future to Beijing. Second, Ukraine is losing faster than Russia. Ukraine’s forces are beleaguered along a too-long front and increasingly reliant on what looks like press-ganging for recruits. The country’s energy infrastructure is 80 percent damaged or destroyed. The third fact: Donald Trump’s election is throwing all the old assumptions about the war into doubt.

It is a sign of the odd times in which we live…

British chief of the defense staff Sir Tony Radakin’s observation that the last month was the bloodiest yet for the Russians, with casualties amounting to about double their monthly recruitment rate, underlines the degree to which Moscow is working to a timetable. Even with the equivalent of a division of North Koreans — whose participation in the fighting has yet to be confirmed — this is unsustainable in the long run. Instead it appears to reflect a determination to ensure that by the time Trump is inaugurated as president again, Ukraine’s Kursk salient has been squeezed back and the front line in the Donbas is as far forward as possible.

If Trump really does intend to try and impose a ceasefire, Putin wants it to work as much to his advantage as possible. He can either use it as an opportunity to reconstitute his forces, ready for a resumption of hostilities at his convenience (presumably after he has manufactured some pretext to allow him to claim that Kyiv is to blame) or else let the conflict freeze, with Russia in de facto control of almost a fifth of Ukraine.

There is, of course, trouble brewing at home. Inflation is almost at 10 percent, with some food items costing 25 percent more than a year ago. The labor market is at full stretch, and the more soldiers Putin raises, the greater the pressure on the industrial workforce trying to arm and equip them. Some police forces are a quarter understaffed, and the organized crime rate has doubled since February 2022. For now, though, this is all bearable: Putin will not likely have to face serious guns-versus-butter questions until 2026 and even then, he faces stagflation and decline, not collapse.

Ukraine, for all the evident resolve and fighting spirit of its people, is under sharper pressure. It is not yet clear just how cold the winter will be and just how disastrous the effect of Russia’s systemic attack on its energy infrastructure will be, but one British diplomat in Kyiv admitted that they feared it might be the straw that breaks the back of Ukrainian will. That sounds a little overblown, but it is clear that there is a growing sense of war-weariness across the country.

Meanwhile, a combination of systemic challenges and questionable decisions mean that the issue of military manpower has still not been resolved. The decision to send all fresh recruits and draftees to new brigades means that the veterans with their hard-won experience are being ground down at the front, while the reserve is untested. The US decision to unlock the wider use of the longer-range ATACMs missiles has been welcomed, but as is often the case, it comes late, and there are questions of just how many of this missiles the Ukrainians still have in their arsenal.

The irony is that Kyiv seems to have a better grasp of its long-term strategy than does Moscow, with plans to develop the domestic defense-industrial complex, broaden its array of air defenses and woo foreign investment. The question is whether it will have the time to implement it.

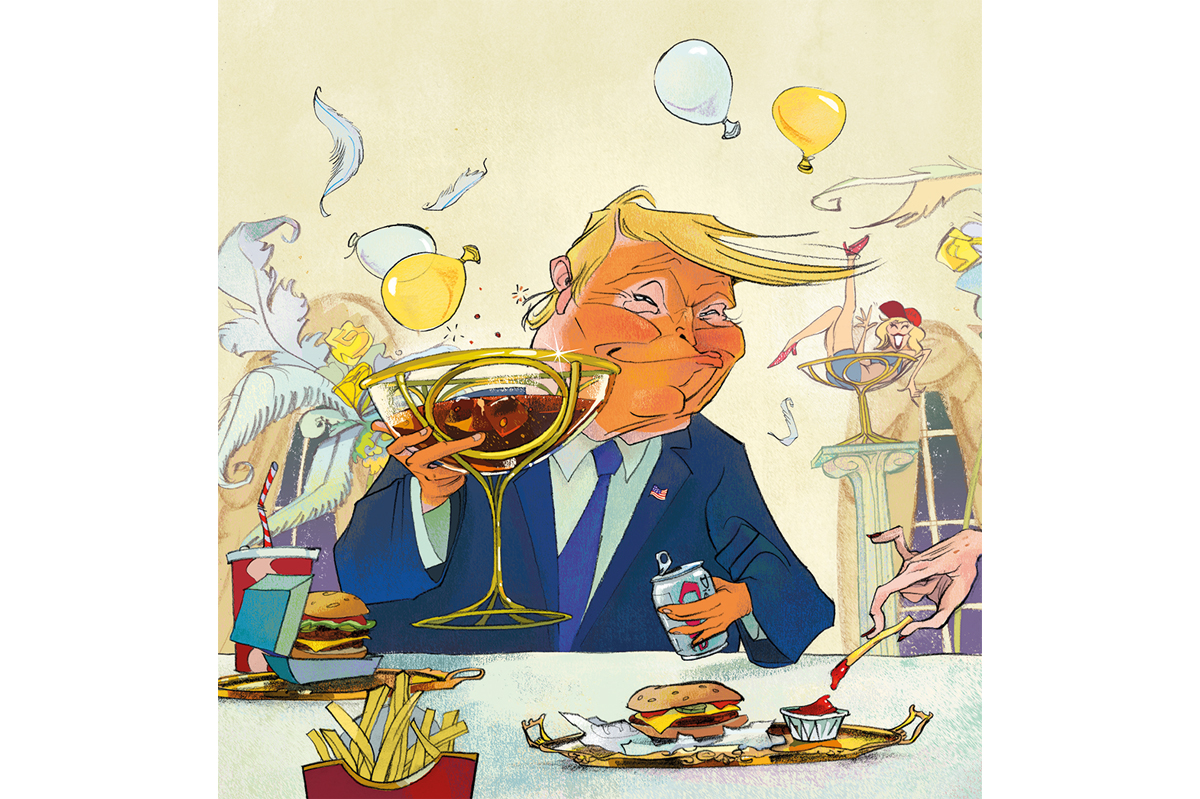

Much will ultimately depend on the United States, or rather the “disrupter-in-chief” Donald Trump. He has, of course, claimed that he would end the war quickly, the plan seeming to be at least to secure a ceasefire — a real, lasting peace will take complex negotiations and concrete security guarantees likely beyond his patience and gift, respectively — by threatening Kyiv with a suspension of aid, Moscow with the war’s expansion.

So far, so helpful for the Kremlin. However, one should not underestimate either Zelensky’s capacity to influence Trump in the coming months or Putin’s capacity to wrest defeat from the jaws of victory. His spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, in response to a suggestion from Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of freezing the front line, described it as “a priori unacceptable” for Russia, and although Moscow’s usual negotiating tactic is to start high and hard, presenting unrealistically ambitious demands as if they are the irreducible minimum, it is possible that they will overplay their hand. If Trump feels he is being taken for granted a ride or, worse yet, being made to look like a loser, then he could as easily swing Kyiv’s way, and if so, he would be unlikely to display the hesitancy and careful titration of support that has characterized Biden’s presidency.

It is a sign of the odd times in which we live that it may yet be that it is Trump who ends up being Ukraine’s savior.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.