The commission

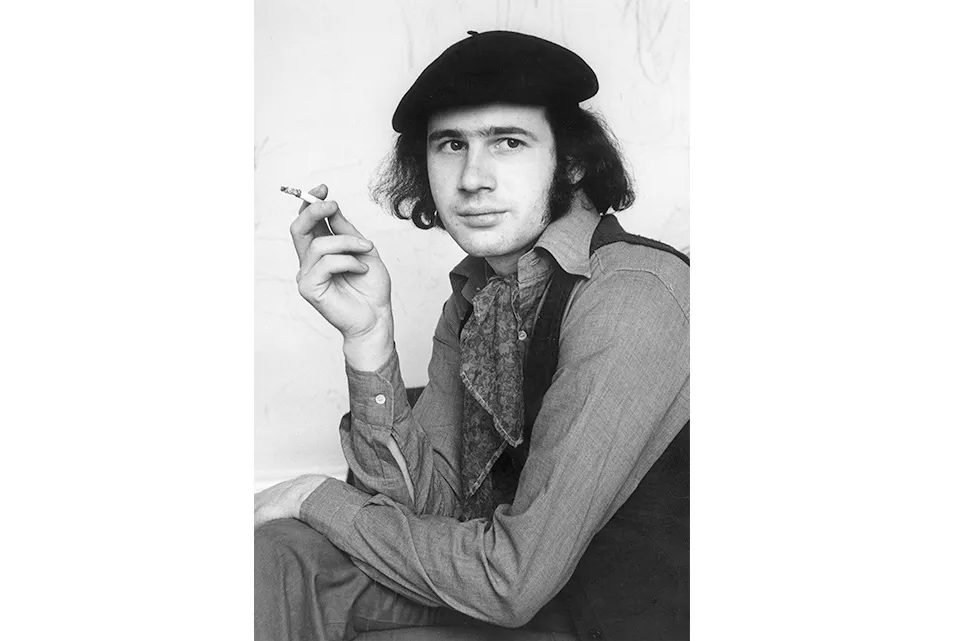

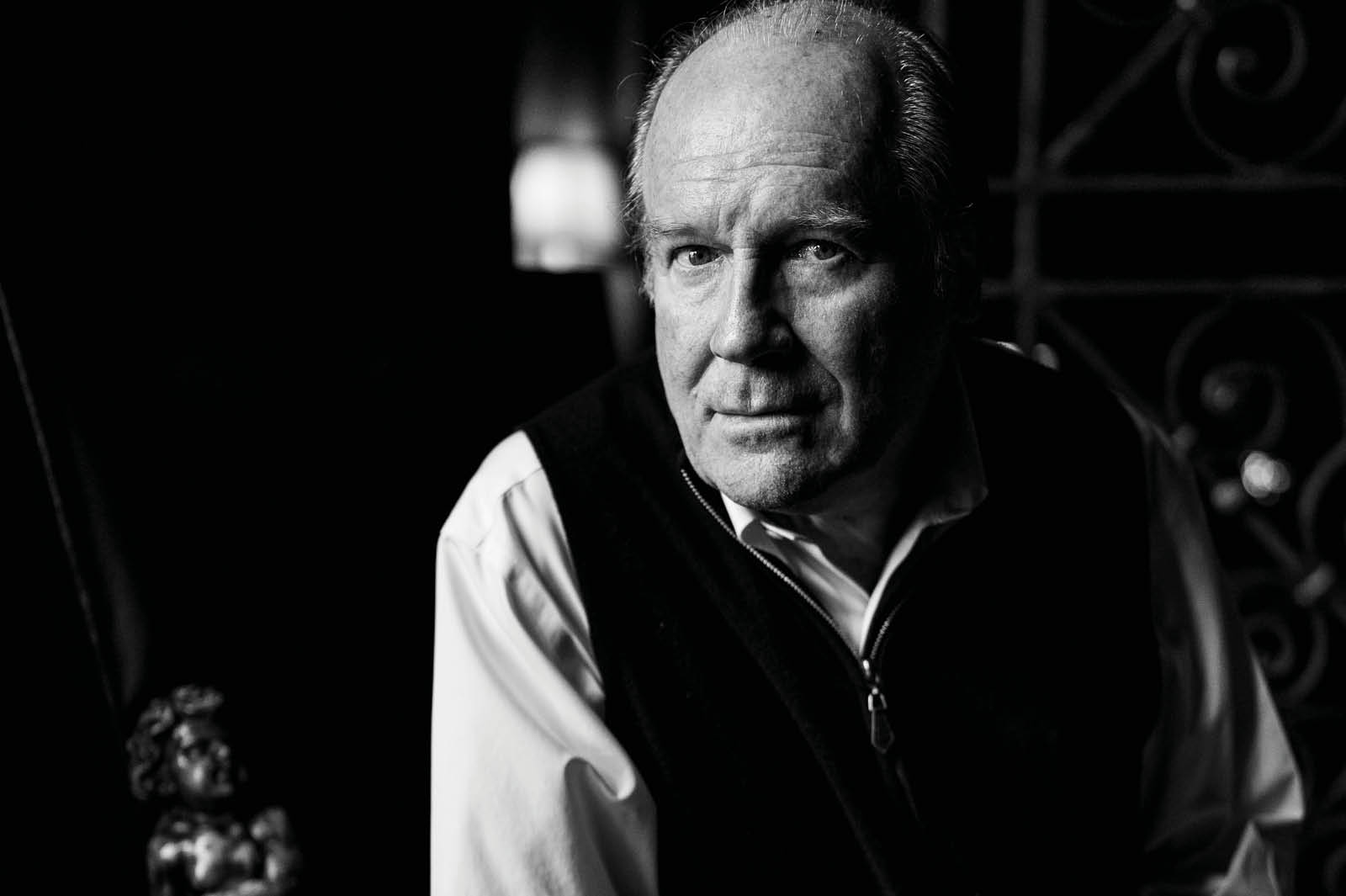

Thirty-four years ago, in the summer of 1990, I had a call from my Hollywood agent, Geoffrey Sanford. Lord Richard Attenborough, the film director, would like to meet me to discuss a project. I said “Yes, please,” instantly. The timing was good — I had delivered my fifth novel Brazzaville Beach to my publishers and was awaiting its autumn publication.

I met Dickie, as everyone called him, with his co-producer and right-hand woman, Diana Carter, in Blake’s Hotel in west London. The subject of the meeting was a proposed film of the life of Charlie Chaplin, a passion project of Dickie’s. But there was a complication. A script had already been written by Dickie’s old friend, the actor-director-producer Bryan Forbes. The very long script, well over 200 pages, had been wholly rejected by the Hollywood studio that had paid for it, Universal Pictures. I wasn’t to rewrite Forbes’s script but to start from scratch, using two books as background source material: Chaplin’s autobiography and the authorized biography written by David Robinson. I agreed to have a go.

This initiative was made on the part of the studio, Universal, in an attempt to create a filmable screenplay. To this end, most oddly, I was not, while writing, to consult with the director — Dickie — but was to work instead with a young studio executive who would be sent over to London to, as it were, ensure the project was properly ring-fenced. Luckily for me this young executive — a senior vice president — was English, smart and genial. We clicked almost immediately. Let’s call him Ford Madox Ford. I — we — had six weeks to come up with a screenplay that Universal would happily finance. The budget was high for such a biopic — $40 million (close to $100 million today). Universal, it was already clear, was trying to be as risk-averse as possible. I went to work.

The writing

Charlie Chaplin was a very strange, very complicated man, full of contradictions. All fond images of the Little Tramp should be banished. He was a borderline pedophile — one of his wives was fourteen years old when he married her. He was, in the 1920s, the most famous person in the world, such was the global reach of silent films. He was what would now be described as very left-wing but had become a multimillionaire who ran his own studio with an autocrat’s whim. His mother was incarcerated in an asylum in Lambeth while he became America’s most loved comedy star. There were many demons in Chaplin’s life.

Ford and I pondered what type of biopic might act as a template or model for ours. We both agreed that Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull struck the ideal tone and style to explore the malign contradictions in Chaplin’s life. My biggest decision turned out to be where to end the story. It started in the music halls of pre-World War One in Lon-on. Then came the silent-movie triumph in the US, then the extraordinary wealth and the power — and then the McCarthyite witch hunt against Chaplin, orchestrated by J. Edgar Hoover, who saw Chaplin as an unabashed communist hiding in plain sight. It seemed to me that the fitting end of this extraordinary journey was when Chaplin was banned from living in America in 1952. The country that had made him eventually threw him out.

The first draft of the screenplay that I presented to Dickie was very dark, very warts-and-all. I suspect — though he never said so — that he was a bit shocked. Chaplin was a real hero to him. However, the studio was very happy. The film was greenlit before the end of the year. Filming was set to begin in February 1991.

The problems

I was fortunate to have Ford as an ally. I got on very well with Dickie Attenborough and became very fond of him. He was a delightful, charming, charismatic individual. However, I had a hotline to the thinking at Universal thanks to my relationship with Ford and, even though the studio liked the new script, they thought the film’s budget was way too high. They began to look for ways not to make it.

Meanwhile casting and pre-production were well underway. Robert Downey Jr., then only twenty-five, was cast as Chaplin. It was a measure of Dickie’s generosity that he invited me out to Los Angeles to look at the key locations. Not many screenwriters experience that privilege. And then Universal began to throw spanners into the works.

One day, to my surprise, Dickie asked me if I had heard about Tom Stoppard coming on board. I was both shocked and surprised. The script was written, had been substantially revised and we were good to go, I thought. But no, Universal (which had Stoppard under contract) wanted him to do a “dialogue polish,” as it’s termed. I called Ford to protest. He thought it would never happen, he said, that’s why he hadn’t told me. But because of the impending Stoppard-polish the start date of shooting was pushed back.

I think with hindsight that this was part of Universal’s delaying tactics. What was not to like about a dialogue polish from one of the world’s leading playwrights? Who could object? When I was in LA with Dickie I also witnessed a furious phone call between him and the studio when they asked him to defer his fee as director/producer. He refused vehemently.

Luckily, I’ve kept a journal since the age of eighteen. All these events of more than thirty years ago are covered, in great detail, in its pages. Memory is a dog that wants to please its master, someone once said. Rereading my journal for this article makes it very clear how much one forgets, how transformative and fickle memories are. I can only quote chapter and verse, dates and times, because I wrote the account of the Chaplin story as it was actually happening.

Universal started playing hardball. They said they would only put up half of the budget of the film — Dickie now had to find a partner. He went to Columbia, which had made Gandhi. They passed. The film was clearly in freefall. The LA and London crews were laid off. Those actors who had been cast now looked for other jobs. Downey, however, stayed loyal. He would wait, he said, and see if the film could be refinanced. He told me once that he had been “put on earth to play this part.”

In these dire circumstances only Dickie Attenborough could have managed to have Chaplin made. Somehow, he found a new studio, Carolco, a so-called mini-major, which would pick up the entire tab. Carolco was rich, and responsible for the Rambo franchise and several Arnold Schwarzenegger films — so what did they see in Chaplin? Respectability, kudos? Anyway, they were now running the show. The Stoppard polish was dropped and Carolco had its own ideas about the shape of the film. And they didn’t like my ending.

By now my link with the production was over, effectively. I had been paid by Universal, as had Tom Stoppard, but I stayed in close touch with Dickie and Diana, who kept me posted on the film’s progress. They had gone back to my final draft but were, I was almost 100 percent sure, lightening its darkness. And the executives at Carolco, for some bizarre reason, wanted to see the older Chaplin, in his eighties, in his Swiss exile, with his young wife, Oona, and family.

The legendary William Goldman was hired — at vast expense — to write these new Swiss scenes. A voiceover was being added, I was told; Anthony Hopkins was to play the role of Chaplin’s publisher, supervising the writing of his autobiography, allowing him license to reminisce. Downey consequently had to age-up fifty-odd years. He was not happy.

From time to time, Dickie would invite me to the shoot in London to see some of the big set pieces. One night there were 200 extras at Smithfield Market, doubling for Covent Garden. William Goldman was there as well and Dickie introduced us. I was a great admirer of Goldman — I could remember my rapt fascination watching Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid when it was released. But Goldman, it was instantly apparent, was shocked to see me there. Two writers on the set! He barely spoke to me, made his excuses and rapidly left.

The credits

William Goldman had made one thing clear to Dickie. He wanted a writing credit on the movie. He had written substantial new material and so his claim was valid. However, this meant that the allocation of the writing credits would have to be decided by a Writers’ Guild arbitration, a kind of star chamber. No one knows who is arbitrating and the judgment is final and beyond appeal. Bryan Forbes had the right to ask for a credit as well — which he duly did, even though there wasn’t a comma of his first screenplay left in the final shooting script. There had been a rift between Forbes and Dickie as a result of Universal’s wholesale rejection of his script. A thirty-year friendship was in jeopardy. So I, Goldman and Forbes each wrote a document outlining why we were entitled to a credit. The Writers’ Guild judges deliberated and came up with this: “Screenplay by William Boyd, William Goldman, Bryan Forbes.”

Because I was still part of the Chaplin family I was invited to an early private screening of the film at Dickie’s Richmond house. I was agog to see it. By now it was July 1992, almost exactly two years since that first meeting. Here’s what I wrote in my journal:

Well, the film is OK. Some great scenes. Goldman’s Swiss scenes and voiceover are very bad, badly written, clunky, fake. Downey is superb — he carries the entire film. It feels somber, dark — a penetrating character study rather than a straightforward biopic. Not many laughs… But I like its darkness, its inherent melancholy. The story of a real human life — moving, unsettling. It disturbs. Real art does this.

I still hold to that early judgment even though Chaplin was a commercial flop when it was released, just as I still hold to my judgment about Goldman’s wholly inept contribution to the film. His scenes jar terribly. If I were ever to give a class on screenwriting, I would offer up his exposition-laden Swiss scenes with the old Chaplin (“You were the most famous man in the world, with your own studio named after you”) as precisely what not to do when you write a screenplay. I’ve no idea what got into him.

I was also, of course, keen to see what remained of my original screenplay. Quite a lot, I was pleased to note. I deserved my first-writer credit at the end of the day. I would say about 75 percent of Chaplin was written by me; 20 percent by William Goldman and a covert, uncredited 5 percent by Dickie and Diana Carter.

The coda

The ups and downs of the story of making Chaplin are an example of the usual crazy rollercoaster that happens when you make a film. There are more horrifying stories, believe me. But it got made, thanks to Dickie Attenborough. Robert Downey Jr. was nominated for an Oscar in 1993 (and he should have won — Al Pacino did for Scent of a Woman). Funnily enough, I became friends with both Tom Stoppard and Bryan Forbes after the film came out. Bryan and Dickie duly buried the hatchet. Ford Madox Ford seems to have entirely disappeared off the Hollywood and cinematic radar for some reason.

It’s a measure of Dickie Attenborough’s thorough decency as a human being that he unilaterally decided to give me half of one percent of his own gross-profit participation in the film. Net-profit participation, widely offered, is known as “Monkey Points” because only a monkey will expect to see any money.

Anyway, once or twice a year, I receive a small check — a few hundred dollars — representing my half-percent of the gross profits of the film Chaplin. Thirty-odd years have gone by, and the trickle hasn’t diminished. With each check I raise a glass to Dickie Attenborough. I think he would be pleased. Those small checks are the proof that the film is still being watched on various platforms around the world — and is still making money. Chaplin, for all its travails, is still alive.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply