“God help the English if she ever starts on us,” remarked Jonathan Keates in a blurb for Mavis Gallant’s Paris Notebooks. Far from being the ubiquitous “love letter” to a city, the essays and reviews within revealed people and their lives as they were, not as ideals. What Keates didn’t realize was that in Gallant’s short stories, everyone, regardless of nationality or gender, was fair game for her sometimes vicious, often dryly funny, always unblinking gaze.

When she died in 2014, aged ninety-one, an obituary noted her profound irritation at her critics’ focus on The Collected Stories of Mavis Gallant: “Everyone who has reviewed it so far mentions exile.” What seemed to her unwillingness to recognize her writing in a broader sense can be seen as the romantic problem of a literary trope which shows no sign of abating. It shows how Gallant might be in danger of being perceived now, reduced to caricature by readers fixated on a dreamy positivity or longing; see the TikTok-ification of Sylvia Plath and Franz Kafka.

It is no stretch to read a connection between the harshness of Gallant’s childhood and her need for control over how her writing was perceived. The premature death of her father and — at best — the indifference and, at worst, exposure to neglect and sexual abuse from her mother created a young woman who was an exile from any sense of normality, devoid of any romance.

Working as a journalist in Montréal around the end of World War Two, Gallant’s desire to move abroad was rejected by her husband, which resulted in the end of the marriage. Likewise, while she enjoyed her work, it was clear that as a woman she was considered temporary until the return of the men. Between such casual sexism and her realization of how content people are to accept stasis, Gallant had the guts to make the running. The impact of these realizations was strong enough to become an underlying theme in many of her “abroad” stories.

When she sold a second story to the New Yorker for $600 in 1950, she left Canada to embark on a writer’s life with a decisiveness many of her future characters could only dream of. Helped in part by her editor William Maxwell, “who let me think it was perfectly natural to throw up one’s job and all one’s friends and everything familiar and go thousands of miles away to write,” the world was now Gallant’s stage.

Despite being a nearly lifelong expatriate in France, she was disinclined to fawn over the stars of the Parisian literary firmament. Gallant’s opinion of Simone de Beauvoir pulls no punches (though she was fond of Sartre, who was kind to her early on): Beauvoir she summed up as “drunk… a royal idiot,” while her 1970s review of Beauvoir’s memoir All Said and Done describes her style as “the dazed, ruminative rhythm of a French schoolgirl chewing gum at a concert in time to Bach.” Gallant loved France, but she was also determined to write it as she found it.

In interviews at the end of her life, she comes across as friendly but with low tolerance for what she considered frivolous or pointless questions, which results in interviewers’ reactions varying from cautiousness to terror. She doesn’t seem to have suffered fools gladly, which confirms the impression she felt she never had time to waste, in writing or life. This meant no other marriages, no children and, she intimated, the freedom to live as she wanted sexually.

This clarity of intent and her astuteness about human nature would still be considered bold today in those neopuritanical circles where forthrightness is seen as undesirable. For an unfettered woman choosing to live in another culture, Gallant’s attitude was nothing less than revolutionary, part of the beginning of the great wave of freedoms to come.

The forthcoming NYRB Classics publication of The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant brings together short stories spanning the 1940s to 1980s. As with her previous writing, they are a mix of domestic and international vignettes, offering a psychological continuity alongside her other work throughout the world’s changing social and sexual landscape. In Jhumpa Lahiri’s introduction to the earlier collection The Cost of Living, she recalls asking Gallant how her stories evolved over time. “It’s just a straight line to me,” said Gallant, holding up a beaded necklace.

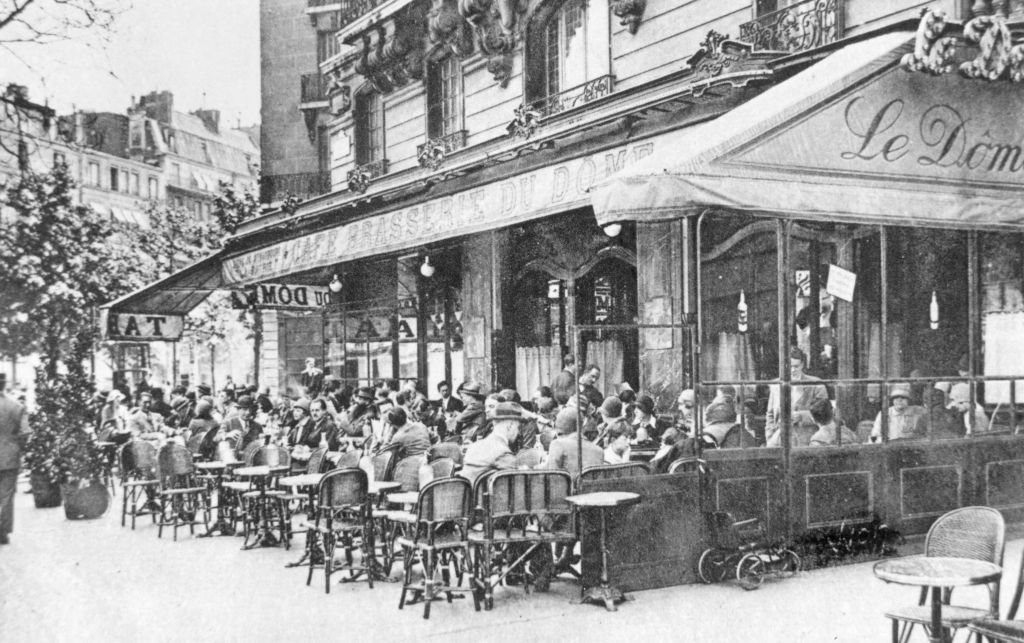

The standouts in this new collection are the Parisian and European stories. Brought together, they focus on the naive or egotistic observations of cultures distorted by human superficiality. This is nothing new – it was a preoccupation of writers such as Henry James and Edith Wharton, Americans abroad who saw their characters as innocents led astray – but it is executed elegantly here. For Gallant’s characters, travel rarely results in an expansion of the self; it reveals truths about how her protagonists see the world and themselves.

Gallant’s expatriates, tourists and assorted travelers have always groped their way through her stories, only hazily aware of whatever culture they find themselves in. In both cases, her early, journalistic observation of stasis serves her well: characters are unable to participate in lives that go beyond what they’ve previously imagined. However you choose to frame it — privilege, naiveté, lack of imagination — they come across as a study in possible outcomes of her own life. had she never left Canada.

“Jeux d’Été,” for example, is a witty account of how contemporary countries can become identikit simulacra of one another, with the same cultural and retail opportunities, with its three privileged female characters moving through Europe in synchronized ennui. Gallant brutally juxtaposes the sexual perspective of the (male) hotel staff with the young women’s inertia:

The girls had been looking at things in Italy and were shortly to be looking at things in Greece. They had looked at everything in Paris, in Nice, in Florence, in Rome and in Venice, all in less than four weeks.

“American women are said to have the finest legs in the world,” one of the dining-room waiters remarked, as if he had been deceived.

Just as an Instagram post functions to validate self and create a storyline, Gallant’s stories show characters with a fixed idea of who they must be outside of their home countries, regardless of whether they’re permanently abroad. You can imagine her cool, disdaining eye and prose effectively dissecting such narcissism now. In this sense her stories can be read through the applicable prism of social media; plus ça change.

Money and sex, two of her main themes, provide much of the motive force; Gallant’s protagonists are sometimes, but not always, wealthy. Likewise, sex, or the specter of it, only adds to discomforting realizations. In “Better Times,” destitute Guy, living in a relation’s house in France, attempts to convince his very young bride Susan of his castles in the air: “Luckily there were the nights. At night he could still promise her anything she wanted and make her believe in the prospect.”

Rare outliers are depicted as alien both to their own cultures and new ones, shown to great effect in “Virus X,” where sickly Lottie arrives in Paris from Canada to study, only to be dragged about Europe by her hometown acquaintance Vera. Uniquely, Vera is an outcast due to a rumored pregnancy, “shipped abroad to an exile without glamour.” Social structure, imagined or otherwise, forms the only real borders acknowledged by Gallant characters abroad. Without it, they cannot see how to fit into their surroundings. While Vera lives in a culturally liminal chaos, Lottie’s experience is in part an actual fever-dream as she is dragged from pillar to post according to Vera’s whims and the pair’s funds.

In approaching her stories as a kind of human comedy, an omniscient view of experiences internal and external, often abrupt or without resolution, Gallant imbues them with both fullness and fragility, which owes everything to the woman who left for Paris with nothing but $600 and a fierce desire to write.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply