The first scent of trouble came when Cuba’s government ordered all its non-essential workers home. By packing them off (and there are plenty of them, given Cuba is one of the world’s last centrally planned communist states) the government hoped the island’s exhausted national power grid would get a breather. It didn’t work, the main power station crashed, and Cuba went dark. At first, I didn’t think it was a big deal. Power cuts in this all-but-bankrupt state have long been a daily scourge. But it turns out there’s a categoric difference between twenty and twenty-four hours of blackout.

I came to Cuba in 2018 for a three-month stay and here I am, now married with a three-year-old son. Friends call this my “Cuban midlife crisis,” which I resent. I’ve been absorbed by Cuba, by its highly educated people who, starved of opportunity, have turned to art, music, jokes and ideas to help them survive or, indeed, escape. I’m often told stories that would have broken me like a twig. My friend Catalina lost her father when he tried to flee across the Florida Straits and drowned. She was two. When Catalina was a teenager, her mother was sent to jail. Yet Catalina still managed to receive a PhD in linguistics.

The current crisis is due to the increasing obsolescence of Cuba’s power plants. My pal Patrick compares them to Cuba’s classic cars, the 1950s Chevy Bel Airs and the Ford Fairlanes that everyone loves, and the Ladas that arrived from Russia in the 1970s. Cuban ingenuity and desperation keep them going, but no one actually wants to spend much time in their gasoline-fumed interiors.

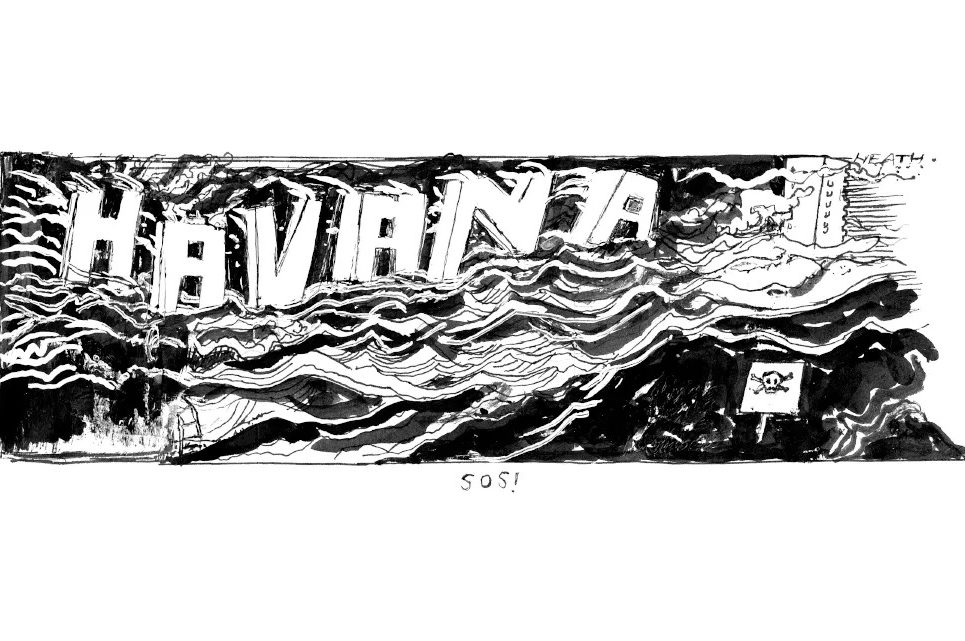

Hurricane Oscar crashed into Cuba’s east during the blackout, tearing off roofs and flooding houses close to the sea. The state used to be very good at responding to such disasters — authoritarianism has its advantages — but it seems they’ve been slow to react this time. Videos show people desperately pleading with Cuban president Miguel Díaz-Canel to get them clean water to drink. So far seven are dead, including a child. “Fidel would never have let this happen,” is a common refrain.

One night, after the sun has set, I go for a walk. It’s quiet and so dark that Havana’s side streets are like black holes; to go down them risks tripping into an open drain or an overflowing trash pile. There’s no one about apart from a patrol of soldiers, so I go home.

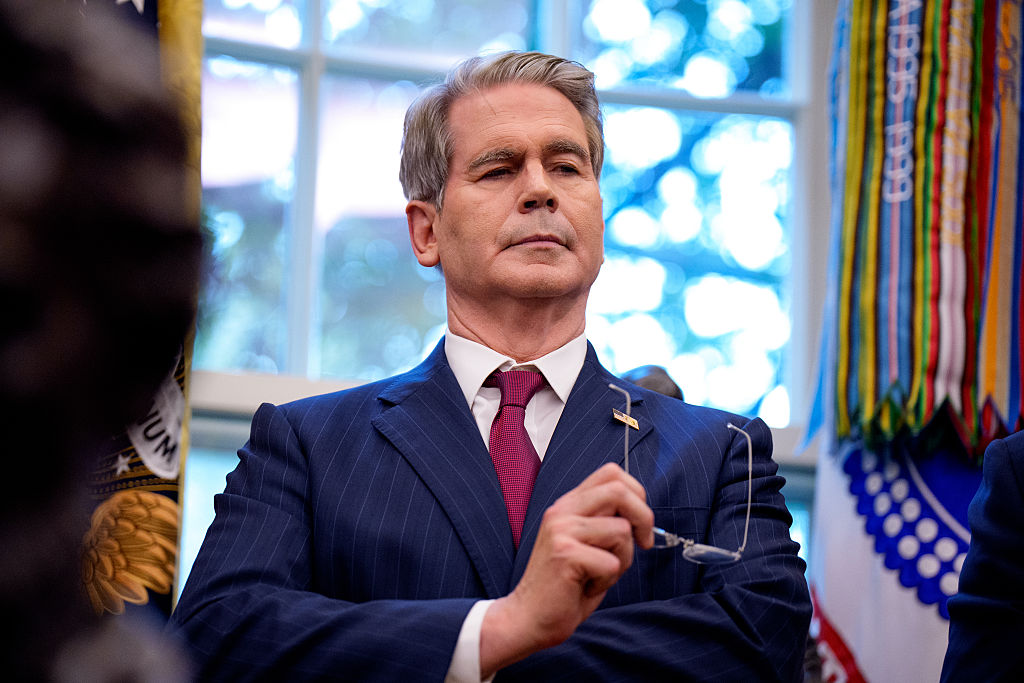

I call my friend George, the British ambassador, in the hope of charging my computer. He’s coming to the end of his stint here, and is widely perceived to be a huge success, a great patron to Cubans trying to start private businesses as well as to the city’s dance floors. His official residence is a fabulous pile, built by the banker Pablo González de Mendoza. It has a famous indoor swimming pool modeled on a temple to Aphrodite. He tells me his generator exploded on the first day of the blackouts, and so they too have no light, and have had to flush their toilets with water from the pool. I find this news so cheering that it gets me through the weekend.

Inflation is a long-term problem. People’s state salaries have reduced in value to around $6 a month. The little food they can afford spoils without refrigeration. The government says Cuba’s many problems are all America’s fault, that they’ve been bankrupted by Washington’s sixty-two-year-old embargo. There is much talk of the heroic workers from the Union Electrica, striving “incessantly” to restart the grid. I track down a retired engineer who worked in Cuba’s big power stations for thirty years. The stories he relates are terrifying, of a turbine hall so hot he had to run out for a cold shower every ten minutes, of political management who would disappear whenever a crisis began, of machines “built rotten.” As the electricity begins to return in fits and starts, it makes me admire the workers all the more.

My wife and I go to the headquarters of the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution, once the heart of the surveillance state, to drop off things for people made homeless by Hurricane Oscar. Cheery volunteers separate my little boy’s old clothes from my in-laws’ spare medicines and adult clothes, ready for the 600-mile truck journey east. They ask to take our picture, but we demur. There are Habaneros here who are really suffering and are giving up what little they have.

No one here believes we’ve seen the last of the crisis. The blackout has further damaged the equally antiquated water supply. I find the prospect of being without water far more unsettling. I speak to Imandra Castañeda and Luisa Linacero, two old ladies gossiping outside a house in Havana. “This has been very hard,” says Imandra. “I have never seen this before.” “We have to keep going,” says Luisa. “There is no other option,” says Imandra. “We cannot die.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.