It seems a fitting end to an ill-fated premiership. As Theresa May prepares to leave No. 10, a major quarrel erupts between her government and its most powerful ally, the United States of America. Leaked diplomatic cables show Sir Kim Darroch, the British ambassador in Washington, calling President Donald Trump ‘inept’, ‘insecure’ and ‘uniquely dysfunctional’. The funny thing is, the words in his memo are just as applicable to Theresa May’s leadership. Within days, Sir Kim resigns.

But every diplomatic crisis is a political opportunity, as President Donald Trump well understands. He even spelled this out in one of his Twitter rants. ‘The good news for the wonderful United Kingdom is that they will soon have a new Prime Minister.’

The message is clear: forget Sir Kim’s indiscretions. Trump wants to reset UK-US relations for the better — or at least to his better advantage. New avenues of transatlantic co-operation are opening up, and Trump is optimistic.

I understand that the vice president, Mike Pence, is planning a trip to London, perhaps a few weeks before the Brexit deadline on Halloween. That is spooky news for pro-Europeans. By then, the new prime minister (presumably Boris Johnson) and the Trump administration may be ready to consummate a brand-new 21st-century transatlantic alliance. In topsy-turvy Trumpworld, everything is possible.

For weeks now, Boris has been saying that if he is elected, Britain will leave the EU on October 31 — ‘do or die’. Might the United Kingdom leap into America’s arms instead? For those capable of looking beyond Brexit, the potential of a Trump-Boris alliance is arguably Britain’s biggest hope.

It’s an open secret that even before Darroch’s emails and his subsequent resignation, Boris had wanted him gone: Sir Kim has made himself infamous in Washington for telling people in private that Brexit is a disaster. To have a UK ambassador undermining UK government policy in Washington is, to put it mildly, unhelpful. And the British embassy in Washington is just too important: the potential economic, security and strategic disadvantages of being on non-speakers with America’s leadership are unthinkable.

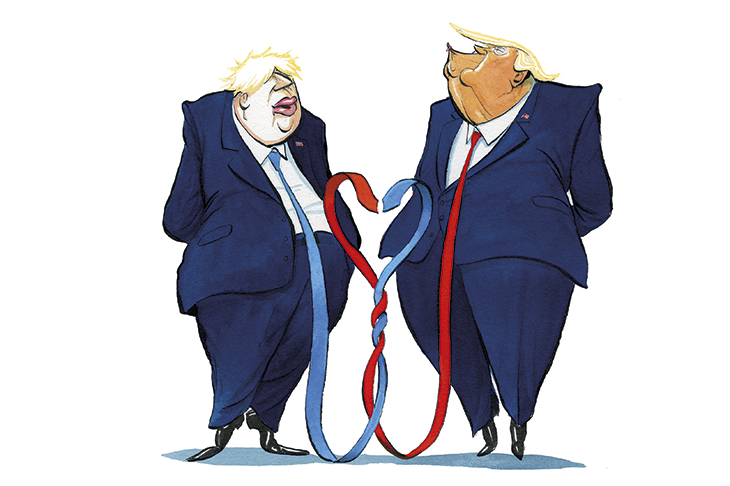

Boris isn’t by nature a pushover, which is one of the reasons that he and Trump will get along. And he seems to understand the president’s mentality: play nice, and Donald returns the favor. The two men have a chemistry that goes beyond their unusual hairstyles and appreciation of younger women. Both grasp that a profound shift is taking place in politics, one that has propelled people like them to power. They also sense, in the way that macho beasts often do, a certain destiny in each other. Trump is possibly the last great Anglophile president: recall his impossibly smug-yet-sweet face as he visited Buckingham Palace last month. Trump likes Britain, Brexit and Boris; it’s that simple.

Boris, for his part, was born in New York, and only gave up his American passport for tax reasons — something Trump can understand. He’s a Churchill enthusiast and therefore an Atlanticist in outlook. He’s always preferred America’s stress on national unity (e pluribus unum) to the fragmented federalism of the European Union. He reveres the way Americans religiously sing the national anthem. He may have dissed Trump in the past, but he wouldn’t be so foolish now. He was accused of being obsequious when he declared to Fox News that Trump is ‘penetrating corners of the global consciousness that I think few other presidents have ever done’. He probably meant it, though. Like almost everything Boris says, the remark was at once silly and true.

Trump and Boris will see each other being attacked by the same kinds of people for the same reasons: offending political correctness, not paying attention to detail, lacking the gravitas high office demands. Yet both men draw crowds and inspire loyalty. Trump and Boris are seen by their supporters as leaders who can shake up a failed system.

Unlike Theresa May, Boris has long appreciated the possible upsides of a Trump presidency. He once told a cabinet minister that he saw Trump as a ‘lifeboat’ that could rescue Brexit. He has also apparently been receptive to the idea — put about by some of Trump’s circle — that after leaving the EU, Britain might join Nafta (or the USMCA, as Trump has rechristened it). Boris’s ideal scenario would be to persuade the EU that, unless it offers Britain a reasonable deal, Britain stands ready to form an alliance with America.

The risk is that, for all Trump’s warm words, he won’t do the United Kingdom any great favors. Sir Kim was quite right to say that Trump’s United States is ‘still the land of America First’. The president will always put his country’s (and his own) interests above any loyalty to his Scottish blood.

And let’s not forget that there is fierce anti-American (never mind anti-Trump) sentiment in Britain. We’ve all read the horror stories of Britons being forced to accept chlorinated Yankee chicken, or looking on helplessly as rapacious US healthcare giants dismantle the National Health Service and suck the profits back to Wall Street. Brexiteers can shrug most of that off as pro-EU scaremongering. But it would be naive to imagine that the ‘beautiful’ free trade deal Trump has promised Britain would not involve substantial concessions to the US.

Worse, an acrimonious Brexit on October 31 could leave Britain stuck in the middle of the Atlantic without a paddle. Far from using Trump’s offer of friendship as a bargaining tool with the EU, as May could have done in 2016, Boris might find himself grasping at America’s hand of friendship at pretty much any price, without having any powerful allies on the continent to fall back on. In this scenario, we can expect Boris’s critics to say that we have gone from being America’s poodle to Trump’s bitch.

Happily, Boris has a hard-headed understanding of the reality of international amity. As foreign secretary, he banned the term ‘special relationship’ because it made Britain seem ‘needy’ — like a neurotic ex-wife, perhaps. ‘I’m not sure that [the term] is much used in Washington,’ he said last year. ‘As in so many romantic relationships, there’s an asymmetry.’

Given Boris’s romantic entanglements, the analogy does not inspire confidence. His historical sense of realpolitik, however, could be useful as he seeks to divorce the European Union while wooing Team Trump. One difficult decision Prime Minister Johnson might have to take early on: should he tear up Britain’s huge order for 138 American F-35 Lightning fighter jets? The RAF wants to do just that, thinking Britain only needs a few dozen. But would Boris dare upset the Donald by welching on the deal?

When Trump visited London last month, Theresa May kept trying to remind him that ‘we do more together than any two nations in the world.’ But Trump, or at least some of his circle, must have remembered how Britain failed to take advantage of America’s enthusiasm for Brexit when he was newly elected. In 2017, when May went to Washington, the first leader to visit Trump, he was talking about offering Britain a trade deal there and then — to hell with the legal obstacles. Steve Bannon, then Trump’s chief strategist, was in the room. ‘He tried to coach May,’ he tells me. ‘He told her to get on with it, because time was her enemy, not her friend. He also offered to do a bilateral deal with the UK. You could tell she didn’t really comprehend what he was trying to tell her. She seemed like a deer in the headlights.’ Trump was inviting Britain to tear up the EU’s rules for conducting Brexit — something that was anathema to Mrs May.

With Prime Minister Johnson, things will be different. As Boris’s Eton schoolmaster said, he doesn’t think that the rules apply to him. Trump feels the same way. Might these two big beasts revive that can-do Atlanticist spirit? Britain is in a weaker position than it was three years ago, having spent the intervening time trying and failing to leave the European Union. But we still have chips with which to bargain.

Take China, for instance. Trump’s robust attitude to Beijing may be a necessary corrective to years of trade imbalances and copyright theft. On his last visit to London, Trump stressed the need for Britain to support him in his tougher stance towards Huawei. Many in Washington see the tensions with China as the start of a new kind of Cold War, and they are looking for allies. Boris is a lifelong enemy of overbearing central governments, and could be a useful junior partner in Trump’s effort. As China emerges as America’s chief strategic rival, Boris and Trump together could pose as the forces of freedom against Premier Xi’s expansive autocracy: a 21st-century version of Reagan and Thatcher.

That may seem an absurd comparison. Reagan and Thatcher were world-shaping figures. Trump is a TV-addicted maniac and Boris a philandering chancer. But it’s worth remembering that the British establishment once thought Reagan was a joke. In 1982, the then ambassador to Washington, Oliver Wright wrote another confidential (now public) diplomatic cable about the president of the United States. Wright mocked Reagan’s ‘homespun philosophy’ and called him ‘an angry man’. He said: ‘we have self-evidently a president — how shall I put this? — whom it is difficult to engage in a serious discussion on any subject of contemporary politics.’

Yet Reagan and Thatcher were serious enough leaders to win the Cold War, revive the fortunes of their countries, and create the conditions for an era of peace and unprecedented prosperity. Might Trump and Boris do the same? Might Boris be able to draw the best from America without making Britain a supplicant? Unlikely things are happening all the time in politics. The emergence of a renewed and successful Anglo–American relationship might be one of them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.