I’m a bit disappointed — déçu, as we Francophiles like to say — with La Maison. When French TV drama is good it can be very, very good, as we saw with Spiral, Les Revenants, and, maybe the best series ever made about spies, Le Bureau. But La Maison is not in their league.

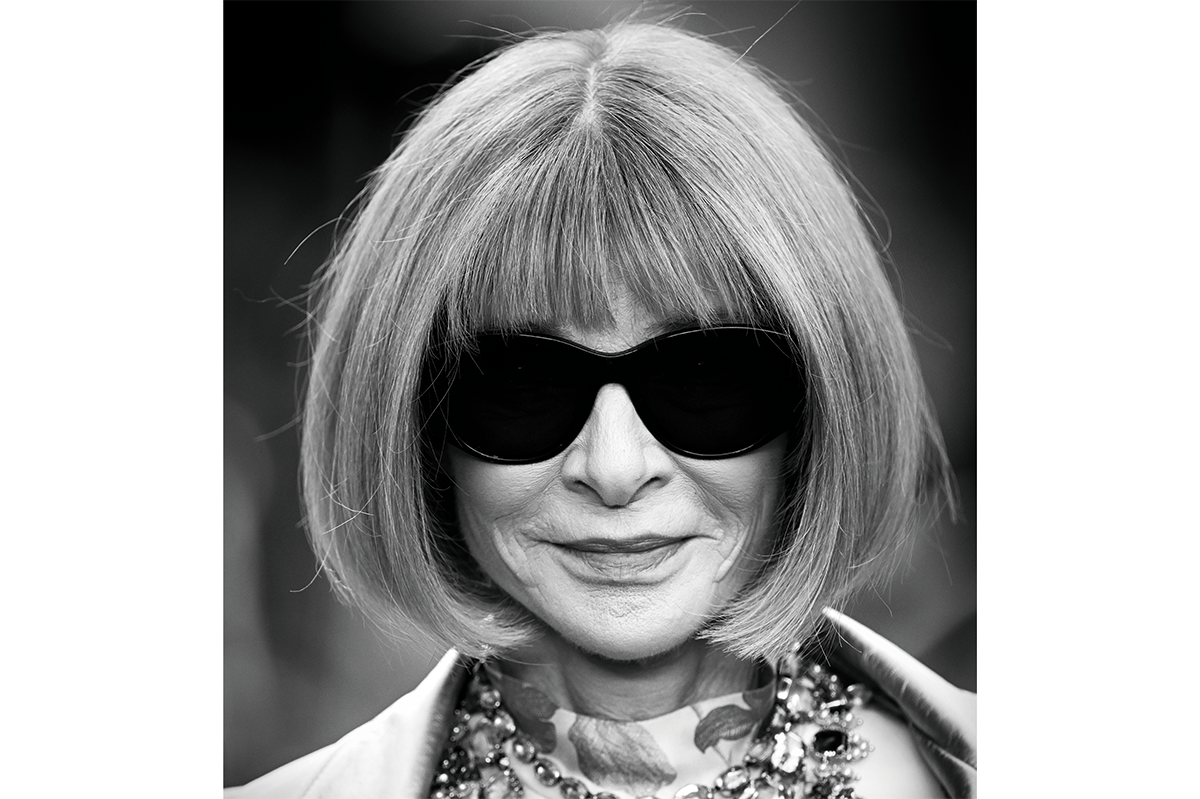

This is a shame because its milieu is not one that has been explored that often in TV serials — and it’s something that a French production really ought to have handled brilliantly: haute couture. Judging by the fancy Parisian settings and general patina of Succession-style luxe, it hasn’t been short of a reasonable budget. What lets it down is that it appears to have no real love for or understanding of its subject matter. This is a fashion series made by people who hate fashion.

To appreciate what I’m getting at it helps if you’ve seen Kevin Macdonald’s recent documentary High & Low — John Galliano. The film dwells, rather too obsessively I think, on whether or not Galliano really meant it when he made some infamously antisemitic remarks one drunken evening, threatening to bring down his then employer, the house of Dior. But much more interesting, to me at any rate, was what it told us about the nature of the industry.

Up until that point, I’d been blithely dismissive of bad-boy designers like Galliano and Alexander McQueen. I thought — pure ignorant prejudice — that because one dressed like a pirate and the other invented weird, kinky things like “bumster” pants, they were probably just shock-of-the-new folks who had been over-promoted to sate the fashion world’s relentless hunger for vacuous neophilia.

But the Galliano film and the 2018 biographical documentary McQueen were eye-openers. For all their manifest flaws, both men were undoubtedly geniuses who understood couture as few creatives have before or since. As with avant-garde painters who have first mastered perspective and how to draw a perfect sphere free-hand, the reason they were able to experiment so ingeniously and productively was because they were grounded in craft and tradition. They were inspired artisans first, and messed up, drug-taking, out-there men second.

This distinction has been largely lost in La Maison. When it depicts a fictional fashion house — Ledu — embroiled in a row after a Galliano-style racist outburst, it offers the viewer no strong reason to care for its plight. Ledu, we are shown, owns a grand building in one of the best arrondissements, has been run by the same family for over a century and has an understatedly elegant, supremely arrogant chief designer who treats his staff like serfs. But the series’s take on all this is not dissimilar to that of a tricoteuse eying the Versailles Palace in 1789: this outmoded privilege is ripe for destruction.

We know this because the most favored character in the series is not the embattled designer Vincent Ledu (Lambert Wilson), nor yet the imperiled fashion house, but rather the annoying, brattish young upstart Paloma Castel (Zita Hanrot), who appears to despise couture. Castel refuses to use real leather, thinks the industry is disgustingly wasteful, is fanatical about the green agenda and goes on guerrilla spray-paint vandalism missions with her urchin girlfriend in their battered camper van. Yet — at least judging by the first couple of episodes — we’re supposed to be rooting for her to replace stuffy, old-fashioned, played-out Vincent and become Ledu’s unlikely savior. What? Perhaps this is just my reactionary prejudice, but why would I want to watch a series where the heroine is a grisly eco-warrior who probably doesn’t even wash, where the enemy is artistry, beauty and tradition, and where we’re supposed to believe it’s entirely reasonable for a century-old institution to be destroyed because a drunk, petulant man has been recorded saying something stupid (in this case about Koreans)?

Well I suppose I might, if the script were as snappy, mordant and funny as Succession’s or if the characters were sufficiently engaging or if the plot were more enticing. So far, though, La Maison feels pretty generic: as if the template for a routine drama about succession issues in a family-run business had just been dropped, at random, on couture, but which could just have easily have been used in a series about the struggle for control of a Lancashire tripe empire.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.