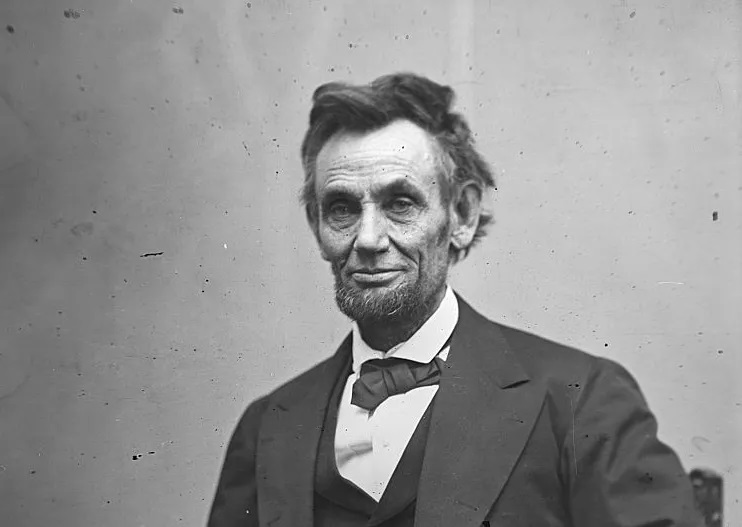

Given the idolatry with which America worships the man widely seen as the greatest president, Abraham Lincoln, and the obsessive place that identity politics now occupies in public spaces, it was probably inevitable that the sexuality of the Civil War winning “honest Abe” would come under revisionist scrutiny sooner or later. And now it has happened.

A current documentary film Lover of Men and a hit Broadway comedy Oh Mary! both suggest that America’s first Republican Party president, who emancipated America’s black slave population, was gay. So what does the evidence say? There is no direct proof that Lincoln ever enjoyed any physical sexual relations with other men. But there is plenty of evidence that he shared his bed with other men — though this was a more common occurrence in the past. Lincoln shared a bed with men both in his youth and as late as the Civil War in 1861-65, when he was a married man. He also got between the White House sheets with a soldier deputed to act as his bodyguard.

Rumors about the future president’s sexual inclinations began as early as the 1830s when Lincoln was an aspiring young attorney in Springfield, Illinois. His stepmother Sarah Bush Lincoln had noted his lack of interest in girls, and his own letters are replete with affectionate endearments to his male friends.

He struck up a lifelong friendship with two men, Billy Greene and Joshua Speed, which frequently included sharing a bed with them. Most mainstream historians, however, point out that men sharing scarce beds in America’s Wild West in the early nineteenth century was far from uncommon, and did not necessarily carry any erotic overtones. At the same time, Lincoln was said to have been passionately in love with a young local woman Ann Rutledge, and anonymously published an elegy poem for her when she died young in 1835.

In 1841, Lincoln married Mary Todd, a southern Belle, and despite frequent titanic rows, the couple went on to have four sons whom they doted on and mourned together when two of the boys died. The relationship endured until the end, and Mary was holding hands with her husband in a private box at Ford’s Theater in Washington when Lincoln was assassinated by the Confederate sympathizing actor John Wilkes Booth in April 1865 in the hour of victory in the Civil War. Mary Lincoln’s grief was inconsolable, and as a widow her severe depression led to her being confined in mental hospitals.

Despite their close relationship, the Lincolns had separate bedrooms in the White House, and when Mary was out of town during the war, Lincoln was known to “bunk up” in the same bed as his bodyguard, Captain David Derickson, which caused gossiping Washington tongues to wag.

In the 1920s, Lincoln’s sympathetic biographer, the poet Carl Sandburg, wrote that there was “a streak of lavender” in the president, and the phrase, which was subsequently removed from the book’s later editions, has been interpreted as meaning that Sandburg considered that Lincoln was gay or at least bisexual, despite his fecund marriage and enjoyment of bawdy manly jokes and stories. Other “Lincolnologists” have pointed out that the ambiguous phrase may merely mean that the president had a gentle and sensitive side to his nature.

Ironically, only one other president — in a long line of heterosexual family men — has been previously suspected of being gay. That was Lincoln’s immediate predecessor in the White House, the lifelong bachelor James Buchanan.

Homosexual writers like Gore Vidal who have previously cast doubts on Lincoln’s staunch heterosexual status have been accused by more orthodox historians of wanting to posthumously “recruit” America’s most revered leader to the swelling ranks of proud out gays, and it is certainly true that those most eager to paint the president pink have themselves been gay.

The divisions between those who are posthumously outing Lincoln, and those who continue to define him as the resolutely straight father of the modern nation, demonstrate that not even long dead historical heroes are safe from the culture wars that are defining and deforming our age.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.