Joe Boyd’s masterly history of what some of us still defiantly call World Music, And the Roots of Rhythm Remain, takes its title from Paul Simon’s “Under African Skies,” but is really less about the roots of rhythm than its routes. A typical chapter will start with a song from a particular geography, then wind the clock back to the country’s history, then forward again to show how that history has contributed to the development of its music, and finally move outwards, following the trade winds as they carry the sounds around the world.

The Argentine singer Carlos Gardel urges the young Frank Sinatra to turn from crime to music

Thus we open with Malcolm McLaren recording in Soweto; jump to Paul Simon’s more successful sojourn there; wind back to the Zulu incursions of the nineteenth century, through the Gold Rush and apartheid and musical censorship; alight on Solomon Linda’s “The Lion Sleeps Tonight;” thrill to the rise of Mbaqanga, the powered-up Zulu jive that combines call-and-response vocals with bass-lines that have the guttural shudder of house renovation; then follow the golden generation of South African jazz musicians out into exile and premature death.

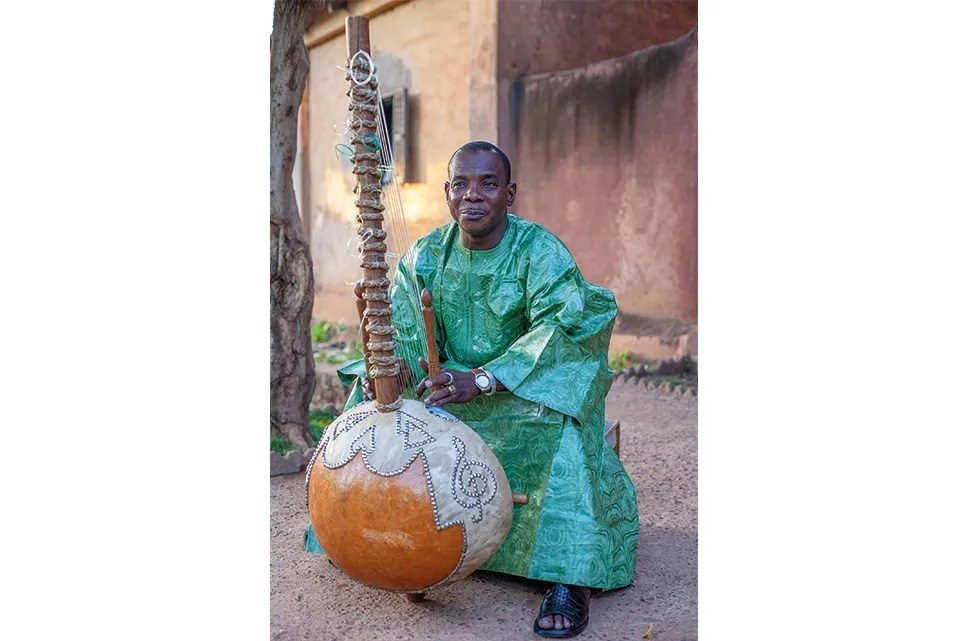

Later chapters perform the same trick with Jamaica, Cuba, Brazil, and with Argentinean tango — where Carlos Gardel urges a young Frank Sinatra to turn from crime to music. A mysterious tape from Bulgaria sets up a wide-ranging discussion of the music of eastern Europe. A concert by Ravi Shankar begins a chapter that encompasses the music of the subcontinent and the influence of the Roma. Having started in Africa, the book ends by covering most of the rest of the continent, including Senegal, Mali, Ethiopia, both Congos and Zimbabwe.

Because it follows the migrations of music and its makers, this is also inevitably a book about empires: the British in South Africa, Jamaica and India; the French, Belgians and Italians in Africa; the Russians in Eastern Europe; and in South America the Spanish and Portuguese and indeed the United States. Boyd is fully aware of the crimes and brutalities of these empires without ignoring the parallel depredations that followed. Many of his heroes, from Fela Kuti to Caetano Veloso, are in and out of prison.

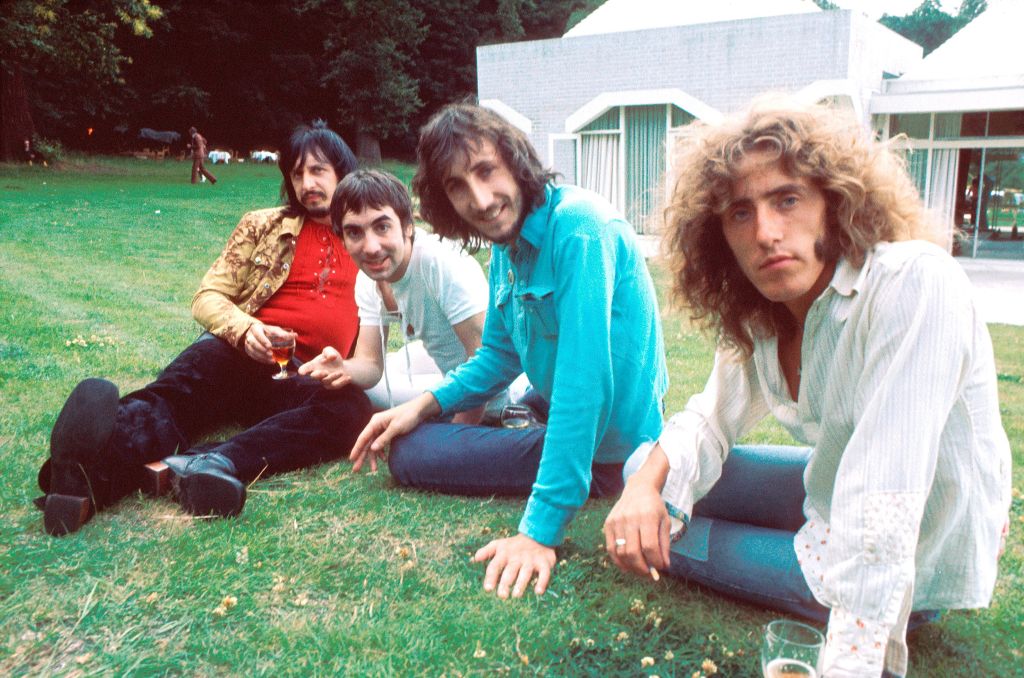

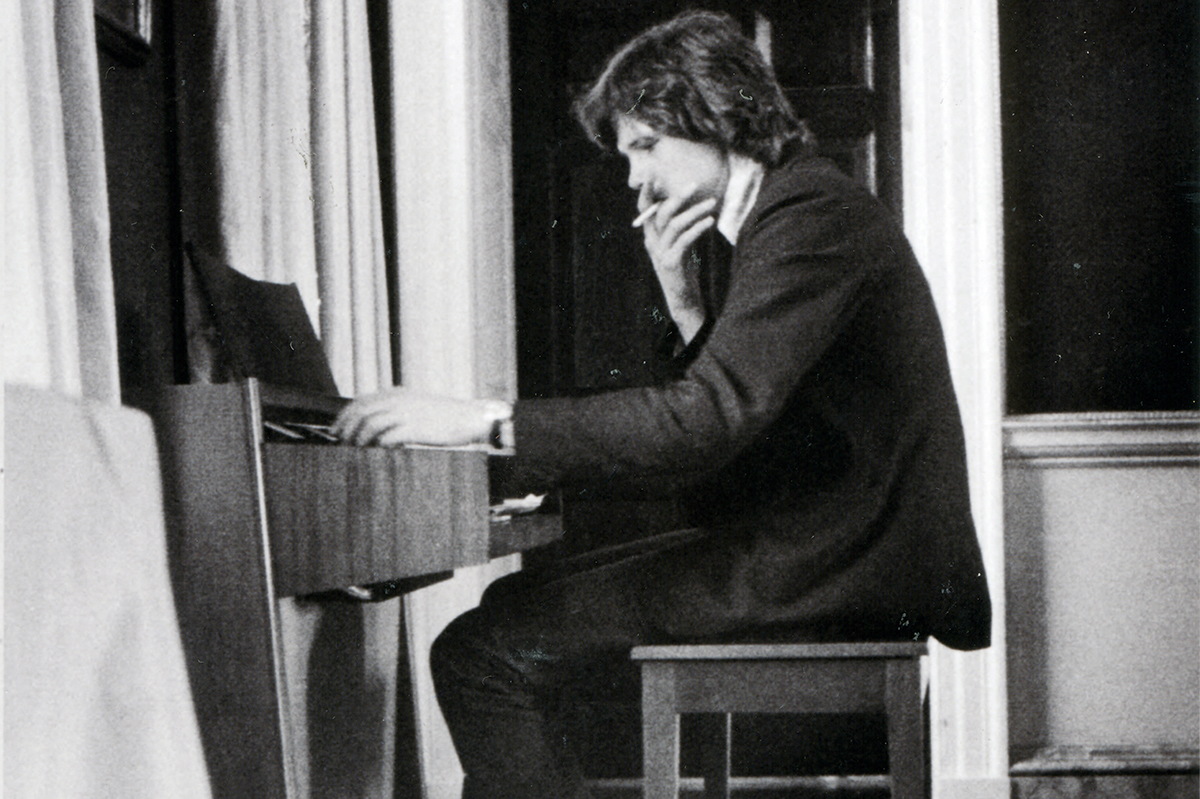

This intersection of history and music makes it sound like a version of The Rest is Noise that slips out of the concert halls to spend time in shebeens and nightclubs and folk festivals. Indeed, the patronage and arbitrary whims of dictators in Brazil or newly independent African states recall Alex Ross’s account of Stalin’s micromanagement of Soviet composers. But Ross never took tea with Tchaikovsky or sunbathed with Schönberg. Boyd is very much a character in his own story. At the end of White Bicycles, his memoir of his early years balancing sound for Bob Dylan, founding the UFO club and producing Pink Floyd and Nick Drake, he boasts that he disproves “at least one Sixties myth. I was there, and I do remember.” Throughout And the Roots of Rhythm Remain, he is again there.

A couple of anecdotes are repeated: a recording session with the South African exiles, and Monica Getz looking daggers at Astrud Gilberto, who has had an affair with her husband Stan. But most of them are new. In Cuba, Boyd records with the cream of a previous generation’s musicians, prefiguring Buena Vista Social Club. When Chris Blackwell dashes to Jamaica to nurture Bob Marley, Boyd produces an album for Toots and the Maytals. He tries to make the Brazilian diva Virginia Rodrigues a star, and has even less success with Pakistan Qawwali duo the Ali Brothers. He is turned down flat as a producer by Youssou N’Dour. But he is instrumental in bringing Toumani Diabaté to western ears, and tirelessly promotes the music of the Balkans and Bulgaria.

Having run a record label, he is also keenly aware of the requirements of commerce and the danger of recording music without any certainty that it will find an audience; he gives full credit to his peers, notably Nick Gold of World Circuit. Boyd was present at the fabled meeting of label owners, DJs and journalists in an Islington pub in 1987 out of which came the decision to promote these disparate sounds as, collectively, World Music.

Most of the musicians covered here hate the term. (Whenever I interview any of them, several minutes have to be written off while they renounce it.) Boyd recognizes the reasons for this allergic reaction; but he rolls his metaphorical eyes at “Global” as a replacement and insists that as a marketing device the term did its work. “How many records would Thomas Mapfumo have sold had he been filed under M-N-O and stuck behind Mudhoney?” In fact, without World Music as a section in record shops, Mapfumo — and all but a handful of the others — would have been lucky to make it in there at all.

Boyd is too clear-eyed to gloss over the uncomfortable truths that the industry prefers to ignore. First, that artists’ expectations are often unrealistic. Virginia Rodrigues “couldn’t comprehend how a rave review in the New York Times, curtain calls in London and [Bill Clinton’s] purchase of 500 copies of Sol Negro for Christmas presents hadn’t made her wealthy.” When her family and friends placed demands on her, it caused a breakdown in her relationships with her western allies. Countless people in Boyd’s position can tell similar stories, which have led to the break-up of bands like Kinshasa’s Staff Benda Bilili.

Second, that the tastes of American World Music fans seldom match those of home audiences:

Cubans reacted to Buena Vista’s triumph with a mixture of sarcasm, fury, contempt and a few cheers. It was as if the world had turned up its nose at Radiohead and Massive Attack, preferring to worship a group of Brit old-timers with banjos and accordions performing George Formby and Al Bowlly songs

The tastes of the musicians may not match with their listeners either. When Paul Simon went looking for South African musicians, they were keener to play Americanized Soul than mbaqanga. Youssou N’Dour angrily turned Boyd down because the producer wanted to record his mbalax live and raw, and the Senegalese superstar craved gloss:

Audiences do seem to enjoy high-tech sounds. A Banjul disc jockey once told [the academic] Lucy Durán that he loved the way N’Dour made a synthesizer sound like a balafon. Most of the singer’s western fans would prefer to hear an actual balafon

Boyd has his blind spots — to which he would probably cheerfully admit. He has no time for Fusion, even though most of the genres he writes about have their roots in multiple fusions. His dislike of synthesizers deafens him to the rare occasions when they are used creatively. He hates Peter Gabriel’s Last Temptation of Christ soundtrack, for example. He insists that Disco sucks, and is largely immune to hip-hop.

These aversions contribute to an elegiac feeling, a sense that the vitality has gone out of World Music. In fact, the genre is in rude health in the form of, for example, Afrobeats; it just sounds less organic than in the 1970s and 1980s. Boyd’s old acquaintance Dylan might have suggested that something’s going on here but he doesn’t know what it is. But none of that detracts from the achievement of the book that Boyd has written: deeply scholarly but grippingly readable — and with the best soundtrack in the world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.