I don’t recall exactly when I first met David Cameron, but it must have been in Oxford in 1985 shortly after the beginning of Michaelmas term. I was a third year at Brasenose studying PPE and he was a first year, also doing PPE.

I remember him being friendly and down to earth and canny enough to keep his political views to himself. At the time, Brasenose was dominated by a group calling itself the ‘left caucus’ and while it wasn’t social suicide to be identified as a Tory, it was a bit infra dig. After Cameron twigged that we were both ‘in the closet’, so to speak, he confessed to me that he was a Thatcherite. ‘Dry as dust,’ he whispered.

He certainly didn’t lack for self-confidence, but he didn’t want to attract any hostility either. He was cautious and alert when venturing into the college bar or the Junior Common Room, like someone on safari who’d decided to get out of the Land Rover to take a closer look at the wildlife.

To be fair, there was no element of condescension about it; he seemed genuinely curious about people from different backgrounds. And he soon dropped his guard and began to make friends. But he never quite shook off the burden of privilege. It was almost as if he felt a patrician duty to present himself and the world he came from in the best possible light.

Most of the time, anyway. In For the Record, his memoir published this week, he includes a long list of things he would have done differently if he had his time again, including joining the Bullingdon. ‘When I look now at the much-reproduced photograph taken of our group of appallingly over-self-confident “sons of privilege”, I cringe,’ he writes.

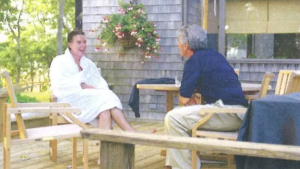

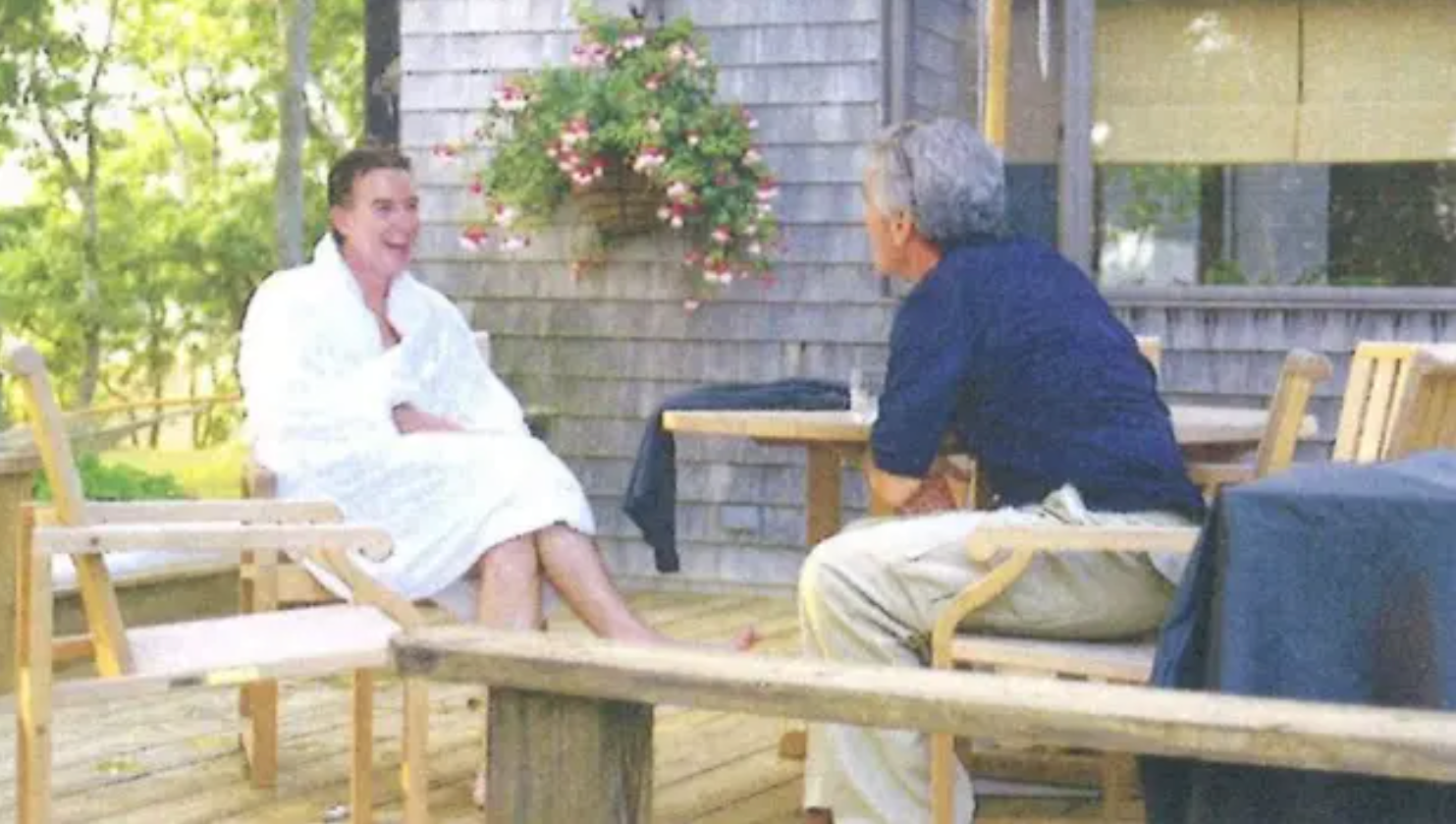

Cameron is often compared unfavorably with Boris Johnson when it comes to how they’ve managed the political difficulty of being so posh. He has attempted to play it down and, in the process, often come a cropper, such as when he appeared to forget which football team he supported. He’s never been guilty of trying to change his accent — remember Tony Blair’s glottal stops? — but his privileged upbringing is clearly a source of slight awkwardness, or was, at any rate, during his 11 years as leader of the Conservative party. I bumped into him a couple of weeks ago, before he’d started promoting his book, and he seemed more at ease now that he’s out of the public eye.

Boris, by contrast, is often said to be more ‘authentic’ because he makes no attempt to hide his background. On the contrary, he hams it up. He has transformed himself into a stock comic character from English popular culture — a lovable buffoon, Billy Bunter with a blue rosette — and traded on the good-humored tolerance that ordinary people feel towards this familiar figure. I think of David as being like Stan Laurel, diffident and eager to please, whereas Boris is more like Oliver Hardy — barreling along, thick-skinned, an ego the size of Big Ben.

But the truth is that David is the more authentic of the two. In regarding his upper-class persona as a source of faint embarrassment, he is conforming to type, anxious to prove he’s worthy of all those silver spoons stuffed in his mouth. As Goethe put it, describing this sense of noblesse oblige: ‘Really to own what you inherit, you must earn it by your merit.’ Boris, who was a scholarship boy at Eton, is the one pretending to be something he’s not. Although, curiously, there’s no deception involved since he makes no secret of the fact that it’s all just an elaborate music hall routine.

I think that’s the secret of Boris’s success, and one of the reasons his pathway to No. 10 has been less effortful than David’s — he hasn’t bothered with authenticity. He realized, long before his contemporaries, that the era in which politicians had to fake ordinariness is now behind us. The public simply don’t buy the idea that their leaders are down-to-earth, normal people any more. So instead Boris has decided to be openly insincere. He’s mastered the art of seeming like he gives a fuck, but not really.

David’s Prince Charles-like sincerity can seem a bit wooden at times, but his efforts to persuade people that you can be both compassionate and a Conservative — to detoxify the ruling–class brand, as it were — helped him win the first Tory majority in 23 years. It remains to be seen whether Boris can win the second.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.