Japanese dancer Junko Hagiwara has become the first non-Spaniard to win one of Spain’s most prestigious flamenco competitions. Yet when Hagiwara went on stage to collect her prize, in La Union in the southeastern region of Murcia, not everyone welcomed her victory. As well as applause, there were whistles and boos from the audience. The Telegraph reported that some of her fellow (Spanish) competitors thought the jury’s decision was a “fix,” designed to boost the Cante de las Minas festival’s international reputation. Francisco Paredes, chairman of the jury, has dismissed the claim as “ridiculous” and “completely false.”

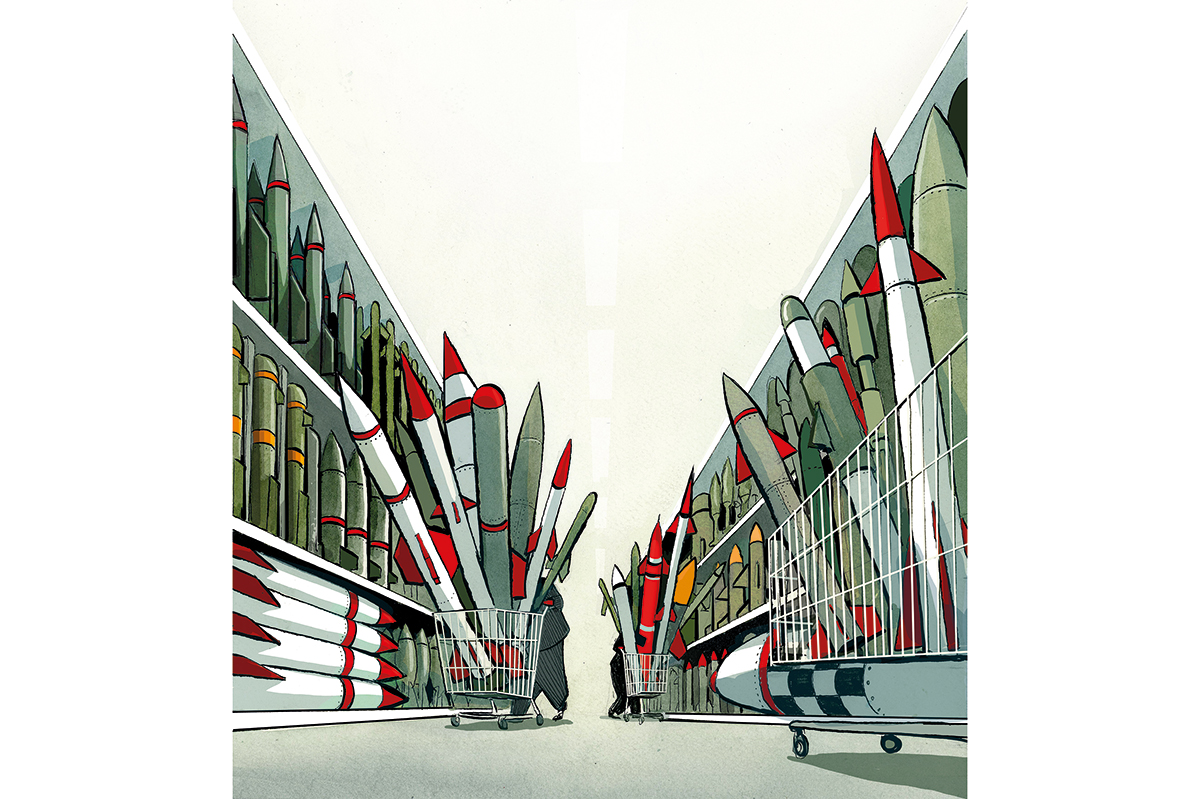

Flamenco has been popular in Japan for a century, and it’s often said that there are more flamenco academies there than in Spain

Even if those who jeered Hagiwara did so because they believed the competition was rigged, it’s hard not to believe that deeper, more hostile attitudes contributed to their reaction. The booers probably believe that flamenco is a thoroughly Spanish art form, and that it’s therefore outrageous that a non-Spaniard was judged best female dancer at the Murcia festival. Aside from being xenophobic and small-minded, though, this attitude completely ignores the art’s complex cultural and historical roots.

It’s true that flamenco, like bullfighting (a spectacle to which it has close aesthetic and philosophical ties), has been a strongly Andalusian tradition for centuries. But its origins can be traced far beyond the Iberian peninsula. Its core musical elements are thought to have been brought to Spain in the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries by the Romani people of India, specifically from what is now Rajasthan. Once imported, it mixed with other musical traditions that had long been a part of al-Andaluz, as Moorish-ruled medieval Spain was called.

Al-Andaluz was founded in the mid-eighth century, by a self-exiled Muslim prince who fled from Damascus to Cordoba, and was itself a blend of Arabic, Jewish and Christian customs. As a result, Romani music was influenced by Africa and the Middle East. This many-sided heritage is evident in many aspects of today’s flamenco: the fandango, a variety of dance and song, has its roots in west African culture, where it means a rowdy musical get-together. And the similarities between flamenco dance and the Indian dance of Kathak are striking, as are the those between flamenco’s plaintive vocals and the adhan, the Arabic call to prayer.

Flamenco has been popular in Japan for a century, and it’s often said that there are more flamenco academies there than in Spain. Curiosity was sparked in the 1920s, when two Spanish films, El Amor Brujo and Andalusia, were released in Japan. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, flamenco became so popular amongst the Japanese that leading artists such as Merche Esmeralda and Paco de Lucia traveled there to perform.

Hagiwara, who lives in the Andalusian capital of Seville and is married to a Spaniard, is not the only Japanese woman to have excelled in the art. In the generation before her, Shoji Kojima and Yoko Komatsbura were credited with turning Japan into the world’s second-biggest flamenco center, and one of Hagiwara’s contemporaries, Yoko Tamura, has also performed at the Murcia festival.

At the core of flamenco is duende, an untranslatable word that also has applicability to bullfighting. In one sense, it signifies an intense emotional state that those related arts can conjure in performers and audiences. I have experienced it, both at flamenco recitals and in bullrings, but it is impossible to describe. Shortly after moving to Andalusia in 2015, I interviewed a flamenco dancer after an electrifying show in Granada. “All the elements were together tonight,” she told me: “the guitar, the singing, the audience. It was duende.” Could she define duende? “No, it’s impossible. But you felt it tonight, right?” I had, but Hagiwara’s detractors would presumably find the idea of an Englishman experiencing duende ludicrous.

Because duende is, in one sense, an emotional state induced by the sounds and sights of flamenco, it transcends nationality. It is universal and can be experienced by anyone who opens themselves up to the music. As Hagiwara herself said after winning the competition: “When I dance, I don’t think I am a foreigner, that I am Japanese… I am simply on stage… and what I feel I express in my dancing.”

If those jeerers in Murcia last week think that Hagiwara is an imposter in an inherently Spanish world, they’re not only guilty of small-mindedness. They also have their history wrong, because flamenco is a unique musical hybrid, forged over centuries by people from at least three continents. It has always been an international affair. And the spirit of duende, as it creeps over you when you experience flamenco as its best, doesn’t care where you’re from.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply