Bitter austerity is biting in Argentina as the new president enacts the brutal cuts he promised in a bid to reign in one of the world’s worst inflation rates.

Entire government departments — including the culture ministry — have been canned and consumer spending has slumped across the board as Argentines find their stacks of pesos aren’t going as far as they once did. In a stark sign of the times, consumption of beef — reared by the country’s rural gauchos — slumped in the first quarter of 2024 by the biggest margin seen in thirty years.

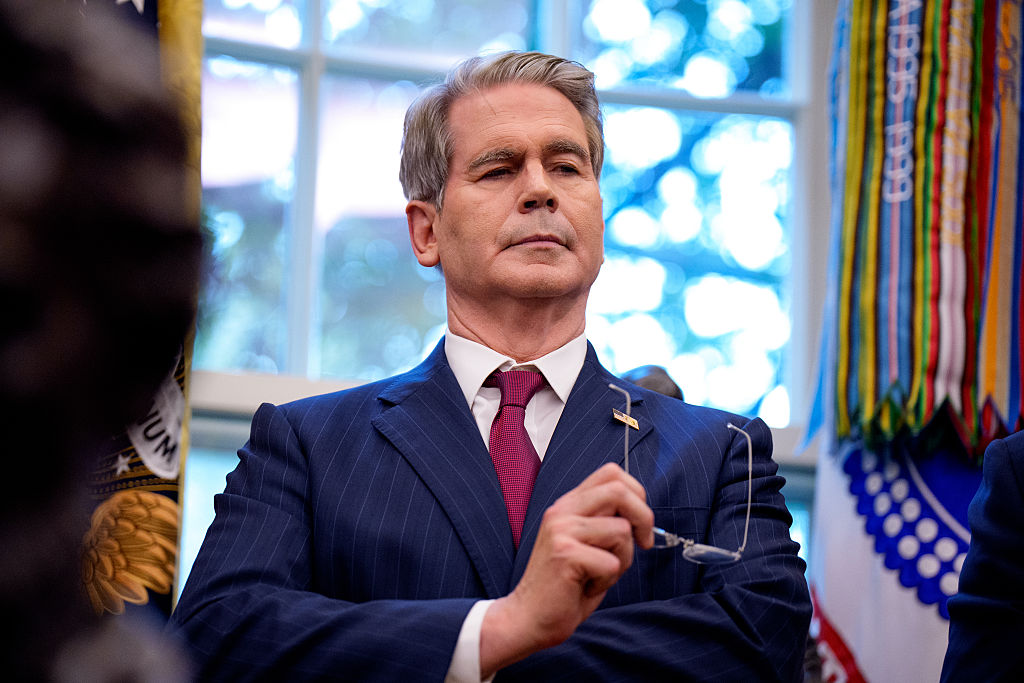

Milei is still attempting to hold things together in congress

However, one area of civic life hasn’t been exposed to Javier Milei’s chainsaw in quite such dramatic fashion. In fact, Milei has not only failed to cut military spending but promised that the budget for the armed forces will increase from 0.5 percent of GDP to 2 percent over the next decade.

Why would he do this when his motto has consistently been no hay plata (there is no money)? Argentina faces no significant or obvious military threats. It is far from the wars enveloping Eastern Europe or the Middle East. Although it aspires to ownership of the Falkland Islands, it — and Milei — has shown no real desire to press its case that strongly. This is reflected in its paltry military spending: currently the lowest as a share of GDP in South America.

The most obvious practical answer is to combat so-called “internal threats” (read: gangs). Although Argentina has not been plagued by violence from drug cartels to the same level as some of its continental neighbors, serious violence has ramped up in recent years in towns like Rosario which serve as vital stop-off points for the cocaine route from northern South America to Europe.

Milei’s security minister, Patricia Bullrich, has promised a strong response, perhaps following the example of El Salvador, where “cool dictator” Nayib Bukele used the military to sweep up tens of thousands of young men, still held without trial. Ecuador has used some of these tactics to clamp down on growing violence and it could be that Milei has a similar idea in mind.

Another explanation is simply that Milei wants to restore the Argentine army to its previously prestigious place in society. The political hero Juan Perón, who gives his name to the Peronist movement which has been synonymous with Argentine politics for most of the past seven decades, was a general and many other leading politicians came from within the ranks of the military.

But the military also has an all-too-recent dark past. Many Argentines are old enough to remember the years of military dictatorship which only came to an end in 1983. Many too will remember friends or family members forcibly disappeared during those years. Independent human rights groups estimate the junta killed 30,000 political opponents, some thrown to their doom from airplanes in the dead of night. The public would likely be deeply suspicious of any attempt to use the military for policing.

Meanwhile, Milei is still attempting to hold things together in congress. His party, a relatively new creation in political terms, boasts just a handful of representatives, leaving him exposed and politically weak. In the latest setback, lawmakers last week approved a triple-digit increase in pension payments to keep up with runaway inflation. The move puts Milei in the position of being the one to veto payments which many older Argentines say they would require to stay afloat. Police clashed with pensioners protesting in the capital this week. The increase would require spending equivalent to an eye-watering 1.2 percent of GDP and, in a post on X, Milei said the objective of the bill was to “destroy the government’s economic program.”

The row is a good indication of the scale of the challenge Milei faces to mould the country’s finances in his image — or that of the Austrian School economists which he idolizes (and named his dogs after). The approach would be an about turn from most of the country’s economic history, and the all-powerful Peronist political machinery will be whirred into gear to oppose him at every turn. Ten months into his administration, the libertarian president will be hoping an upturn in living standards will kick in soon in order to give him a boost going into next year’s midterm elections.

Meanwhile, the reality on the street for ordinary people remains stark. Nearly one in five Argentines are living in extreme poverty, according to recent figures. While Milei will be hoping for an upturn in the economy to boost his hopes of political success, for most the worry is about how to put food on the table. As one of the pensioners protesting told the BBC: “We should have a calm life at home sipping mate [the drink], instead I have to stay here defending my income. It’s impossible to live this way.” If you asked them about their biggest concerns today, the prestige of the military would not score highly.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.