The fact that the Middle East stands on the brink of a catastrophic war can be explained by a scene from The Gentlemen, Guy Ritchie’s preposterous but entertaining series on Netflix about aristocrats and sarf London drug-dealers. The dim eldest son of a duke is in trouble with a vicious gangster, who makes him dress up as a chicken and cluck and dance while the whole excruciating spectacle is filmed. Eventually the humiliation is too much for the aristo: he gets the family Purdey and blasts the gangster in the face — even though he knows that there will be terrible consequences.

The government has told Israelis to stock up on food and water, and ordered hospitals to ready more beds

Iran, too, has been humiliated by Israel’s assassination of Hamas’s political leader, Ismail Haniyeh, in Tehran, in a government guest house, and during a presidential inauguration to boot. As a columnist in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz argued this week, humiliation may be “the single most under-appreciated force in international relations.” So will Iran hit back hard, even if it means a wider war?

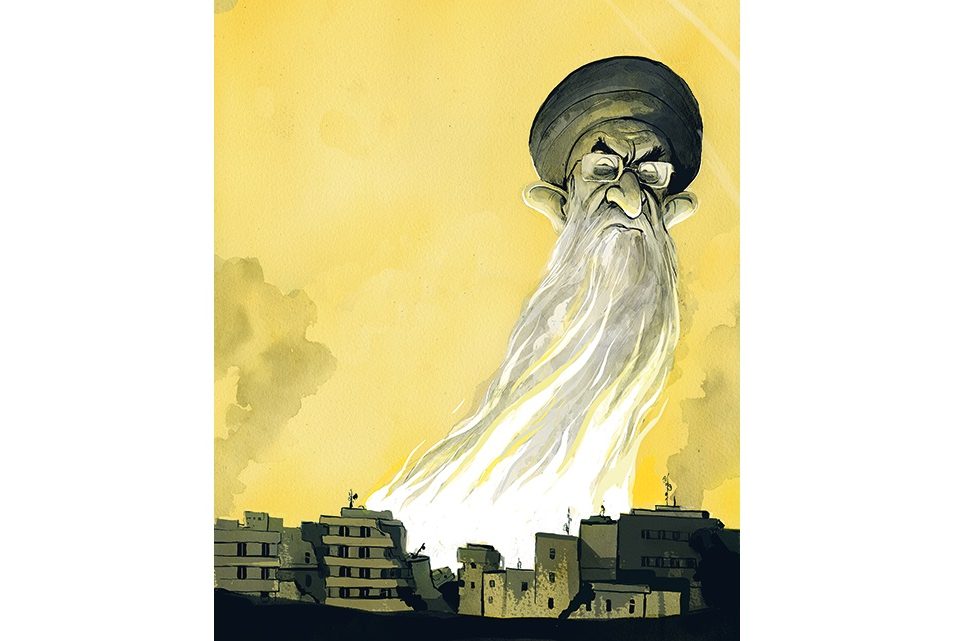

The Iranian leadership’s inflammatory rhetoric about Israel leads some to believe they would self-immolate in an act of holy martyrdom if it meant destroying the Zionist usurper and freeing Palestine. But the mullahs are rational and, so far, cautious. The priority has always been regime survival. Israel gambled on this when it reached into the heart of the enemy’s capital to kill Haniyeh. There will be some kind of military response. Iranian officials have said so to British, French and German diplomats in Tehran. They have closed some of their airspace, presumably to clear the path for long-range missiles. Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei declared that “the criminal and terrorist Zionist regime” had invited a “harsh punishment” for itself. “We consider it our duty to avenge his blood,” he added.

We have been here before. In April, Iran fired hundreds of missiles at Israel after an Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps general was killed in an airstrike at his base of operations in Damascus. Israel’s Iron Dome defense system managed to intercept nearly all the missiles. Those few that got through mostly landed on open ground. The only serious casualty was an unlucky seven-year-old Bedouin girl wounded by shrapnel when a missile hit her village in the Negev.

Opinion is divided on the meaning of what happened in April. The ever-cautious mullahs may have deliberately telegraphed their intent to make sure that Israel was prepared; on the other hand, it could simply have been a convincing demonstration of Israel’s military superiority. Another humiliation.

Either way, Tehran may think that something more is required. The crucial question is whether they choose to call Israel’s bluff by activating Hezbollah, Iran’s client militia in Lebanon. Hezbollah is extremely reluctant to be used in this way. It has been regularly sending missiles and drones across the border with Israel — the bare minimum needed to demonstrate solidarity with Hamas and remain in good standing as a member of the “axis of resistance.” But it has done little more than that. Its cadres are already depleted after years of war in Syria; martyr posters are on every street corner. And the leadership knows that, outside their base of fanatical supporters, the Lebanese people would be furious if they did anything which led to large numbers of Israeli bombs falling on Beirut. The country has yet to recover from a debilitating economic crisis — the currency losing 95 percent of its value — and no one wants another war. However, as a former British ambassador to Beirut, Tom Fletcher, put it, the understandings that govern engagements between Israel and Hezbollah are “fraying.”

Two weeks ago, twelve Druze children in the Israeli-occupied Golan were killed by what appeared to be a Hezbollah missile. Hezbollah claimed they had been aiming at a military target but the missile had been knocked off course by an Israeli counter-missile. Israel responded with an airstrike in Beirut that killed Hezbollah’s military second-in-command, Fouad Shukur.

From Hezbollah’s point of view, hitting one of their people in the Lebanese capital is a violation of those unwritten understandings, the crossing of a red line that demands an answer (irrespective of what Iran might want to do over the killing of Haniyeh). At Shukur’s funeral, Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, appeared on his customary giant television screen to warn of a “new phase of the conflict where all fronts will be open to war.” He said: “We are angry but we are wise. Our response could come from anywhere and any time.”

This suggests — as Nasrallah himself put it — calculated” action designed to avoid igniting a much bigger conflict. Not a rain of rockets and missiles but, perhaps, hitting an embassy. Or an assassination. Or a limited strike against an unambiguously military target in northern Israel.

Yet any such move by Hezbollah will be hard for them to calibrate. The most right-wing members of the Israeli government are already calling for an invasion of Lebanon to “destroy” Hezbollah once and for all. The ultranationalist security minister Itamar Ben-Gvir said: “We must not leave this to our children.” The Israeli media has been full of briefings from the military that, if not ready to take over the whole of Lebanon, they have prepared plans to create a six-mile buffer zone inside it, free of Hezbollah. But as in the short war of 2006, events would quickly get out of control once their tanks crossed the border. Hezbollah is said to have around 150,000 missiles, with the capability to fire some 3,000 a day at targets in Israel. That would be more than enough to overwhelm the Iron Dome.

This is one way the wider war starts. Thousands of missiles are fired from Lebanon. Iran’s militias in Iraq and Yemen join the attack. And Iran itself. The Iron Dome buckles. In response, Israel bombs Tehran and calls on the United States to ensure its survival. The US already has an aircraft carrier in the region and is sending more ships and aircraft, underlining what Washington calls its “ironclad” support for Israel’s security and “right to self-defense” against threats from Iran, Hezbollah and anybody else. Is this what the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, wanted all along: to drag the United States into a war with Iran? Or perhaps he believes that a war with Iran is inevitable and it is best fought on Israel’s terms. American officials hope the slide to a regional war can be stopped with a ceasefire in Gaza. Increasingly, they view Netanyahu as the obstacle to this.

Is this what Netanyahu wanted all along: to drag the United States into a war with Iran?

Exhibit A in the case against the Israeli prime minister is the attack on Haniyeh. This was the man the Israelis were relying on as the go-between with Hamas’s military leadership in Gaza. He was the negotiating partner in the effort to free the remaining 100 Israeli hostages there. The chances of getting a deal, and a ceasefire in Gaza, have been destroyed, at least in the short term.

Exhibit B is a report from Israeli Channel 12 television, accusing Netanyahu of deliberately sabotaging the hostage talks by adding new demands he knows Hamas cannot accept. In Channel 12’s account, the heads of Mossad, Shin Bet and the army, all confront Netanyahu to tell him to take the deal they have negotiated. The Mossad chief says: “If we wait, we may miss the opportunity — we need to take it.” Netanyahu slams his fist on the table and tells the three top commanders of Israel’s security services: “You are weak.”

This report will be widely believed in Israel and plays into the accusation that Netanyahu is keeping the war in Gaza going for as long as he can. Once there is a ceasefire and the hostages are home, his temporary government of national unity will fall apart. He will then face the nation’s wrath for the failings that allowed Hamas to kill 1,200 Israelis in a single day last October. And in an even greater threat to Netanyahu, his trial on corruption charges will resume, with a good chance he will be convicted and sent to prison. (He would not be the first Israeli prime minister to be jailed for accepting bribes.) President Joe Biden was asked by TIME magazine if Netanyahu was prolonging the war in Gaza for reasons of self-preservation. He replied: “There is every reason for people to draw that conclusion.”

That is a devastating verdict from Israel’s most important ally. To be fair to Netanyahu, there are credible reports that in the early days of the crisis last year, he vetoed an attempt by the defense minister to immediately open a second front with Hezbollah. And it was the policy of the entire government, with support from virtually the entire nation, to hunt down all the perpetrators of the October massacre. That would include Haniyeh. Though he was the political — not the military — leader of Hamas, he had also promised to liberate Jerusalem with “a jihad of swords.” Writing about Haniyeh’s killing, the Times of Israel reminded its readers — as if they needed any reminding — of how those behind the murder of eleven Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972 had been hunted down. “For decades, Israel’s leaders have sent a message to their enemies, loud and clear: Hit us and you will die.”

Israel, then, is trying to “restore deterrence.” Knowing the likely cost of this, the government has told Israelis to stock up on food and water, and ordered hospitals to ready more beds. Iran and Hezbollah also believe that they must act to restore deterrence, and no doubt they are well aware of the likely cost too. For years, the Iranian regime jabbed at Israel — and the US — using proxy armies. Now, with their next step, they risk bringing the war home.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply