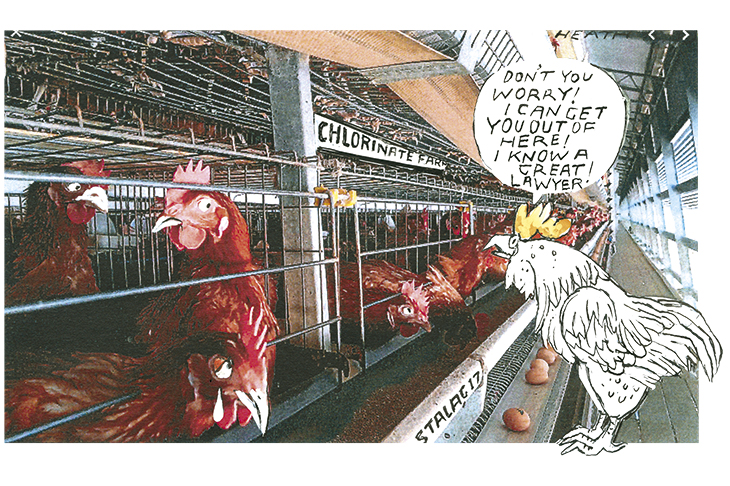

It will no doubt be met with furious resistance in parliament and on the streets. There will be an outcry over chlorinated chickens. There will be scare stories about the National Health Service being sold off. And the farmers will be angry at the prospect of the country being flooded with food that is far cheaper than anything they can produce. Even so, assuming the Conservatives win the election, we leave the European Union and Donald Trump wins re-election to the White House (OK, I will agree the hypothetical is doing some heavy lifting in that clause), Britain and the United States are going to attempt a comprehensive free trade agreement.

That will be a big deal. America and the UK are, respectively, the biggest and fifth biggest economies in the world. They already do trade to the tune of $109 billion every year. But there is plenty of scope to expand that, especially for the UK to sell more to the US. For all its talk of free trade, the United States remains a protected economy, especially in industries the British are good at. There will be huge opportunities in drugs, defense, fashion and media as barriers are gradually dismantled.

It remains to be seen whether, when and how quickly Britain and the US can wrap up a trade deal. First, we must finally extricate ourselves from the EU. Once that is done, we need to work out what kind of trading regime we want, how closely we want to remain aligned with the EU, and how much we want to protect our farmers and other industries from global competition.

There will be sticking points. We might not want to allow American food producers, with their very different production standards, open access to our market. We might have to choose between a US deal and an EU one if Brussels decides it can’t reach an agreement with a country that doesn’t accept its regulatory rules — which is why it has no trade agreement with the US itself.

It will be easier if Donald Trump is re-elected. But in reality, any American president is likely to want to deal with the UK.

The US is already our largest export market, accounting for 13 percent of manufactured goods exports and 24 percent of services. Britain is not quite so important to the US. We are only its seventh largest trade partner (Canada, not surprisingly, is the biggest). But we are also relatively open to American companies. The US sells more to us than to Germany, and almost as much as to Japan, even though both those economies are far larger.

That doesn’t mean that trade can’t increase if barriers are taken down, however. So where should we expect to see the biggest opportunities? Clothing and fashion are one example. The US has imposed lots of tariffs on those products over the years, mainly to try and protect its domestic industry. Shoes already had a 10 percent tariff on them before President Trump’s trade war with China; this has now been raised to 25 percent, affecting imports from the EU, too. That was mostly aimed at the mass market, but it also hit the half-brogues and black Oxfords that are popular on Wall Street. Even Savile Row suits have been affected by extra levies. The UK has a thriving fashion industry that ranges from mega-brands such as Paul Smith and Alexander McQueen to lots of niche companies. All these businesses will benefit hugely from completely open access to the American market. Likewise, speciality food and drink manufacturers should benefit. Scotch whisky is already our largest single physical export, but it too has just had tariffs increased. Take those down and our distillers could sell far more.

It doesn’t stop there. Our drugs industry is one of the most competitive in the world and while giants such as GlaxoSmithKline are well-established in the US, smaller biotech start-ups will find it easier to break into the market if barriers come down. The US imposes restrictions on media ownership that stop British companies from expanding into that market. The US airline industry is currently restricted to companies where a majority of shareholders and directors are American, but in easyJet and IAG, the owner of British Airways, we have two of the most innovative carriers in the world, even if BA doesn’t have many fans these days. The US spends more on defense than any other country in the world — and we have a strong defense industry.

On the other side, plenty of American companies will be eyeing the British market. Food is the biggest likely winner. Within the EU, we protected our market with steep tariffs, but if we take those down, and switch from expensive French and Spanish to cheap American foods, it will give a huge boost to our living standards. Agri-business could do really well out of the UK.

The US has a huge healthcare industry, and lots of competitive, efficient providers. If we can stop being so hysterical about keeping every NHS facility in state ownership, lots of American companies could make it work far better while remaining free at the point of use. American cars might prove a lot more popular if they didn’t have EU tariffs on them, and, in return, our tariff-free Jaguars and Land Rovers would sell better in the US.

Investors confident that a UK-US trade deal can be struck should start looking for opportunities now. On the London market, drugs, food, drink, fashion, media and business services should all get a boost. On the New York market, the huge agri-business companies and the tech giants should be the big winners.

The US and the UK already have one of the deepest commercial relationships in the world. But a free trade deal will still turbo-charge that — and create a lot of new wealth for both countries.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.