Two years ago, Éric Zemmour was the most talked-about man in France and a serious contender to be the ninth president of the Fifth Republic. A controversial journalist turned incendiary politician, he vied with Marine Le Pen for second place behind Emmanuel Macron in the polls. Crucially, he seemed to have something she lacked — an ability still to appeal to the Catholic bourgeoisie while tapping into widespread anger at mass immigration.

But then Russia attacked Ukraine, the mood of Europe changed and Zemmour’s political fortunes sank as quickly as they had risen. He finished a distant fourth in the first round of the presidential election, with 7 percent of the vote. The experience did not put him off running for high office, however, and today he is back in campaign mode looking ahead to the European elections in June and beyond.

He rejects the idea that his 2022 campaign was a failure. “I would call it a huge victory,” he says. He points out that, having founded his Reconquête! Party only a few months before polling day, he still won more votes than Les Républicains and the Parti Socialiste, the two parties which governed France from the time of Charles de Gaulle to the advent of Macronism.

‘The French and the English have battled against each other for the best part of a thousand years’

Zemmour squarely blames Vladimir Putin’s invasion for derailing his candidacy. “The media talked about little else,” he says. His big political theme — what he calls the Islamification of France — was blocked out by more immediate existential fears about a major war in Europe. “There was a rally–around-the-flag effect,” he says. His poll scores took a nosedive from late February onwards. Zemmour’s criticisms of NATO and past praise for Putin got him into political bother. He was also accused of being heartless because he initially said that France should be wary of an “emotional response” when it came to accepting Ukrainian refugees.

Zemmour concedes that he gave his opponents too much ammunition. He has written a book in which he explores his mistakes. Yet he baulks at the suggestion that his pugnacious, journalistic style makes him ill-suited to politics and he’s adamant he’s not giving up. “I fight against the Islamification of my country and the continent,” he says.

Zemmour talks a lot about “the Great Replacement” — a controversial term invented by the novelist Renaud Camus — and he knows that sounds alarmingly racist to many in the West. “It shocks in France, too,” he says. “I am the only one in the political class to use it. Mme Le Pen refuses to use it. She pretends that it has connotations of a great conspiracy… we always have to invent some fascist, Nazi or whatever else origins to everything. There is none of that.”

Camus coined the phrase, he says, “to explain the historical phenomenon which witnesses the replacement of a white Christian — or a Judeo-Christian population of Greco-Roman culture, as General de Gaulle would have described it — by a Muslim population that comes from Africa.”

“French women these days give birth on average to 1.1 to 1.6 children per woman,” he says. “Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian women have about 3.5 children. In France, we do not allow ethnic statistics, in England you do, and we can see that in London only 37 percent of the population now belongs to the category you call ‘white British.’”

It’s difficult to stop Zemmour, whose grandparents were Jewish Berbers from north Africa, when he’s in full flow. He hasn’t much time for the argument that Britain has been better than France at dealing with immigration. “The French and the English have battled against each other for the best part of a thousand years and still we manage to fight over the best way to kill ourselves,” he says. “So the English say, ‘No it’s my multicultural model that is the best’ and the French say, ‘No it is my model, the assimilation turned integration model.’ In truth, both models have failed. Assimilation is only possible individually. We cannot assimilate populations.”

For him, assimilation means adapting to your host country with the zeal of a convert: “It means you change your story, consider Napoleon to be your father and Joan of Arc to be your grandmother, and live like a French man who has been here for a thousand years.”!That seems to be the creed by which Zemmour himself lives. He talks proudly of his Arabic-speaking father, yet he adopts the manner of a nineteenth century homme de lettres. He says chère madame when responding to women, and his speech, studded with literary and historical allusions and the occasional imperfect subjunctive, has a formidable Gallic grandeur.

Zemmour admits he hasn’t a firm grasp of British affairs, though his intellectual self-confidence permits him to say: “England is a republican monarchy whereas France is a monarchical republic.” He spies similarities between the UK supreme court’s obstruction of the Rwanda scheme and the recent rejection of most of the French government’s immigration bill by the Conseil constitutionnelin Paris. In Rishi Sunak and Macron, he says we see “politicians pretending” to care about voter concerns “when they really think that immigration is good because it will solve economic problems.” In both their cases, too, “we are experiencing the takeover by judges over the democratic representatives of the people, which are the parliaments and the politicians.”

This is a long-standing theme of Zemmour’s work: in 1997, he wrote a book called Le Coup d’Etat des Juges. Today he believes that Britain’s Brexiteers made a grave mistake in assuming that their political sovereignty could be seized back from Europe when it is in fact “the judicial oligarchy,” French in origin, that is busily suffocating democracies the world over, from Donald Trump in America to Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel. “In France, since the Middle Ages, the judges come from the church and they consider themselves priests,” he says. “Before it was the Catholic religion. Now it is human rights — but it is always a religion. And they are there to impose that religion on politicians, who must submit.”

Zemmour’s oratory may be powerful, but his party remains far behind Le Pen’s Rassemblement National in the polls. Still, he believes that the decade-long struggle of populism against centrism, as represented by Le Pen versus Macron, is giving way to a new clash of right against left, as an emergent conservative patriotism aligns itself against a dangerous fusion of Islam and socialism.

His concept of “Islamo-gauchisme” might also sound batty to some British ears. Medieval concepts of Sharia do not appear to reconcile themselves naturally to the progressivism of the twenty-first century. But Zemmour insists that the connections between “le woke-isme” and Islamism are becoming increasingly apparent, “since both are allied against the West and western civilization in order to destroy it.”

He places Le Pen on the wrong side of this new Islamo-left versus new right divide. She represents the “somewheres versus anywheres,” he says, referring to the work of the British academic David Goodhart, whereas he stands for a more epoch-defining battle against what he calls the “invasion or maybe even the colonization” of Europe by an antithetical religion. Unlike him, Le Pen believes that “good Islam” can be separated from “bad Islamism” and she is a protectionist whereas he believes in free markets. “She does not see herself as right-wing,” he says.

Doesn’t Zemmour’s reputation for controversy serve to make Le Pen more acceptable to the French middle classes? “Non,” he says flatly. Instead, he regards the rise of Giorgia Meloni in Italy and Geert Wilders in Holland as evidence that he is on the right side of history. Zemmour wants to enlist elements of the British right into this movement, too, even if he accepts that Nigel Farage (whom he met a couple of weeks ago on his visit to London) and the Reform Party do not share his criticism of Islam. He met Kwasi Kwarteng too, though the former chancellor found him disturbingly “obsessed with Islam” in a way that is “not relevant to the UK.”

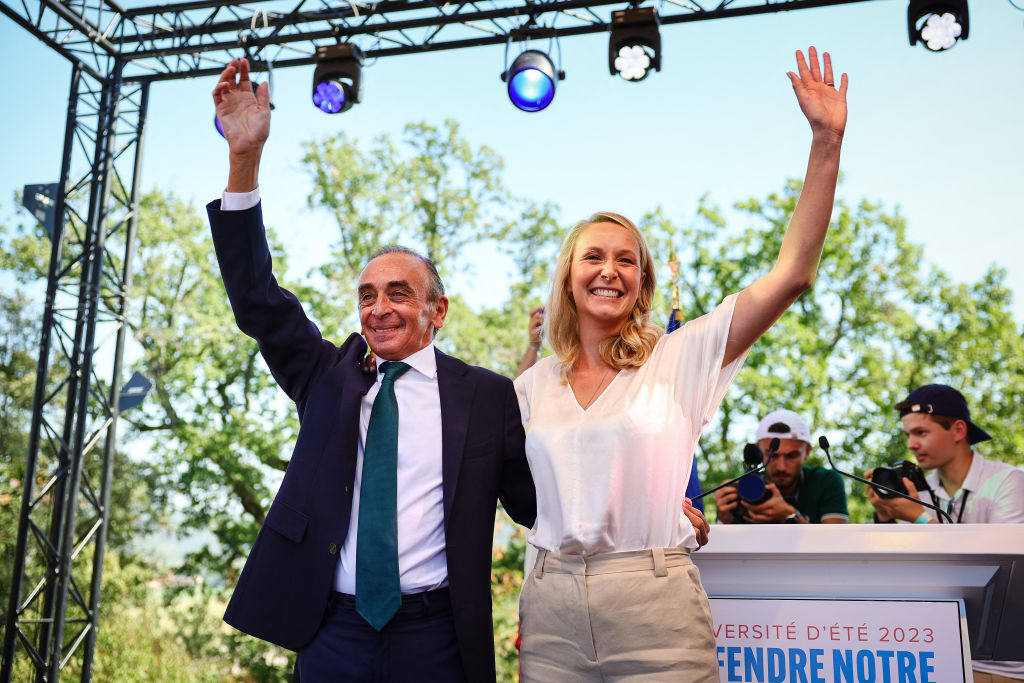

As part of what Zemmour calls “this ideological evolution,” he’s joined forces with Marion Maréchal, Le Pen’s niece, who will lead Reconquête! into the European elections. Maréchal may not win a majority of French seats, but with the backing of other conservative groups across the continent, the new right may well emerge as a majority bloc in the European parliament. “I am not intending to conquer Europe, let me assure you of that,” he says. “What I am saying is this is the division which will impose itself all over Europe and is in fact already happening.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply