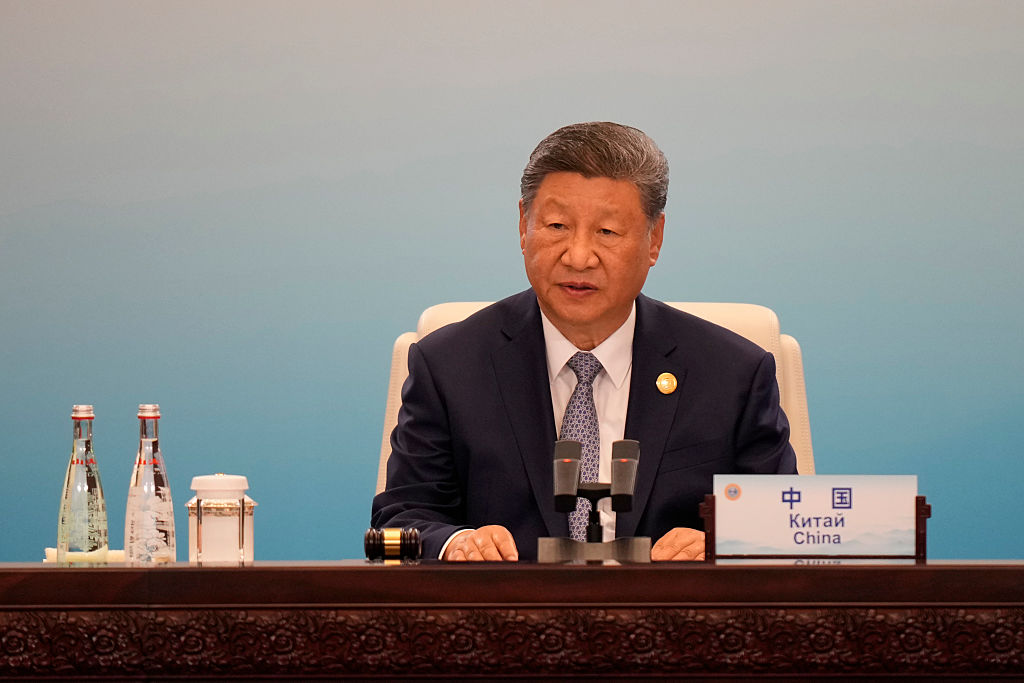

‘Hide your capacities, bide your time’, China’s former leader, Deng Xiaoping, famously once said. Few in the West understood what he meant then. But they understand it today.

The coronavirus outbreak has brought home the reality that China does not play by global rules. It’s time for countries committed to open, liberal democracy, free trade and free markets to accept the reality that China is not a partner but a strategic competitor.

The coronavirus cover-up of the emergence of the disease might even have included lax standards in laboratories as the US Embassy had complained of. These are the actions you would expect from the Chinese Communist party, a crony political monopoly that brooks no dissent, seeks to assert complete control and whose officials are too terrorized to confess to error.

China has also long ignored global norms on trade, distorting its market to favor state owned companies and privileged firms allowing them to undercut foreign rivals, harming producers in developing countries and in the developed West. The textile industry in Central America for example was largely wiped out by huge state-owned Chinese companies.

Many US and European tech and telecommunications companies, which could have given us solutions to today’s tech challenges, simply do not exist because they were driven to bankruptcy by China’s state owned enterprises (SOEs). It was Huawei’s government support of below cost pricing that arguably contributed to the destruction of Lucent Technologies and Alcatel in the 2000s.

China’s investments in Africa involve onerous default terms which include taking over parts of the countries themselves if they are unable to comply with the terms. It then uses its own workers on these large infrastructure projects rather than indigenous ones, attacking the one advantage developing countries actually have.

Geopolitically it has ringed the Indian Ocean, the most crucial theatre of operations in the 21st century, running its ports they will own if the host countries default on their agreements. It seeks to turn the South China Sea into the Lake of China. Its Belt and Road project threatens to be a playground for China SOEs. Be in no doubt that China is a formidable adversary and we must reconfigure the global economic architecture to deal with this reality.

When the UK and US work closely together, good things generally happen for the world’s citizens. The UK and US are still the largest contributors to the IMF, World Health Organization and other multilateral institutions. The UK-US axis is crucial and must be a dynamic partnership injecting views into all global institutions, bolstering a new geopolitical realignment.

Fundamentally we must recognize that trade policy is a branch of foreign policy, not just the summation of what different corporate interests want. Our FTAs will promote open and more liberal trade, free and competitive markets around the world, the protection of property rights, competition and an end to government distortions, presenting reformers in China with something to aim for.

The UK-US FTA will be a cornerstone of our global economic policy, but we can gather a coalition of similarly placed countries, such as the CPTPP countries, especially Australia, New Zealand and Singapore. UK and US policy towards Japan in particular has been benign neglect over the last 20 years, when Japan should be a strategic partner and ally, economically and geostrategically. India, with its 1.3 billion people, at least nominally subscribes to the same economic goals as the UK so we should work together through agreements.

It is now clear that in the teeth of a true crisis, nation states are more relevant than the EU idea. Countries should work with the EU, through the UK-EU and US-EU FTAs to promote a more open and competitive EU, one that is not so hidebound by anti-competitive regulation. But we should also recognize the limits of the EU’s effectiveness, working directly with the Netherlands, Germany and the Scandinavian countries.

And when it comes to developing economies, it’s not just in our own self-interest to avoid failed states and to create markets for our goods. There is a moral imperative to ensure that open and competitive markets in these countries lift the poor out of poverty, rather than leaving them to the mercy of strategic competitors like China or Russia.

The China of 2020 is not the China of 2010, still less the China that acceded to the WTO in 2001, although it still claims developing country status in that organization. It was hoped then that China was on a pathway to becoming a full market economy and a responsible global stakeholder. The financial crisis, the Chinese Communist party’s grip on power and the recent coronavirus handling have dashed those hopes. But we are partners with the Chinese people, just as we are partners with people all over the world who yearn for freedom.

Now we must realign our approach, give oxygen to reform-minded Chinese people and deprive the cronyist ‘planners’ and party functionaries of it. If we are ever to wake from the economic coma that COVID-19 has induced, we must set out on this path now.

Shanker Singham is CEO of Competere and former trade adviser to the UK trade secretary. This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.