I’m back! As I mentioned in my last newsletter, my husband and I recently set off on our ten-day honeymoon to Morocco. We went to Casablanca, Meknes, Fez, Marrakesh, the Agafay Desert and Essaouira. I didn’t travel much growing up and so this trip was really special for me. We toured one of the largest mosques in the world and a fifteenth-century synagogue that is still active today, visited the Roman ruins of Volubilis, trekked through the Medinas, haggled in the souk, watched artisans create their handmade crafts with techniques handed down for centuries, rode camels and enjoyed traditional Berber food and music.

Before we left for our trip, we fielded a lot of safety concerns. We were warned in our guide books that women should dress modestly — no big deal for me — and to beware of pickpockets and scammers who target naive tourists. We booked our trip through a local travel agency that equipped us with a personal driver and a local guide for our official tours each day, but even at times when we ventured out on our own, we never felt unsafe. Honestly, the precautions that I took — storing valuables in a a crossbody bag, keeping to well-lit areas, mapping out walking routes before leaving, saying “no” politely but firmly to street vendors or beggars — were no different from things I might do when traversing downtown DC or New York City. The murder rate in Morocco is far lower than that of the United States, and while there are drugs and theft like anywhere in the world, all of the locals we spoke to seemed shocked and disturbed at the stories we told them of random violent crime in American cities. That doesn’t really happen here, they echoed.

That’s not totally surprising given the emphasis on community, even in the larger cities (with the exception of maybe Casablanca, which is sort of the business center of Morocco and houses a lot of weekly commuters). In the Medina (translated to “Old City” in English), families share a communal oven where everyone bakes their bread for the day or week. At least once a week, Moroccans go to the Hammam for a special washing day and might find themselves scrubbing someone else’s back. It is an unspoken rule in the markets that there is one price for Moroccans, and another for outsiders. A huge part of the Moroccan economy is dependent on tourism, and it was quite funny to watch our guides interact with other locals and be able to tell from their body language that they were in on the “game” together, so to speak. The locals also seemed to have no patience for the migrants from sub-Saharan Africa who panhandled on the street while awaiting possible entry to Europe. Several noted to us that they don’t have respect for people who ask for handouts but don’t want to work.

The importance placed on community also translates, of course, to family. Many Moroccans live in multi-generational homes and share their earnings with the entire family. In the Medina, family members operate their shops downstairs and live together upstairs. We met one woman whose family home was destroyed in the Atlas Mountains because of the recent earthquake. She moved her mother and siblings into her two-bedroom apartment in Marrakesh without hesitation.

The official motto of Morocco is God, Country, King. While it is officially an Islamic country, they are proud of the fact that they are tolerant of other religions. During our tour of the famous Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, our guide spoke with reverence of the similarities between the three Abrahamic religions. In Marrakesh, we took time to pray in a local Catholic Church and to reflect at a historic Jewish cemetery. The five daily Islamic calls to prayer echoed loudly throughout the streets, and while for most, life continued on as usual, tens of thousands would make their way to their local mosque to pray. And everyone we spoke to was not shy about their belief in God and identified it as a unifying and stabilizing force in their country.

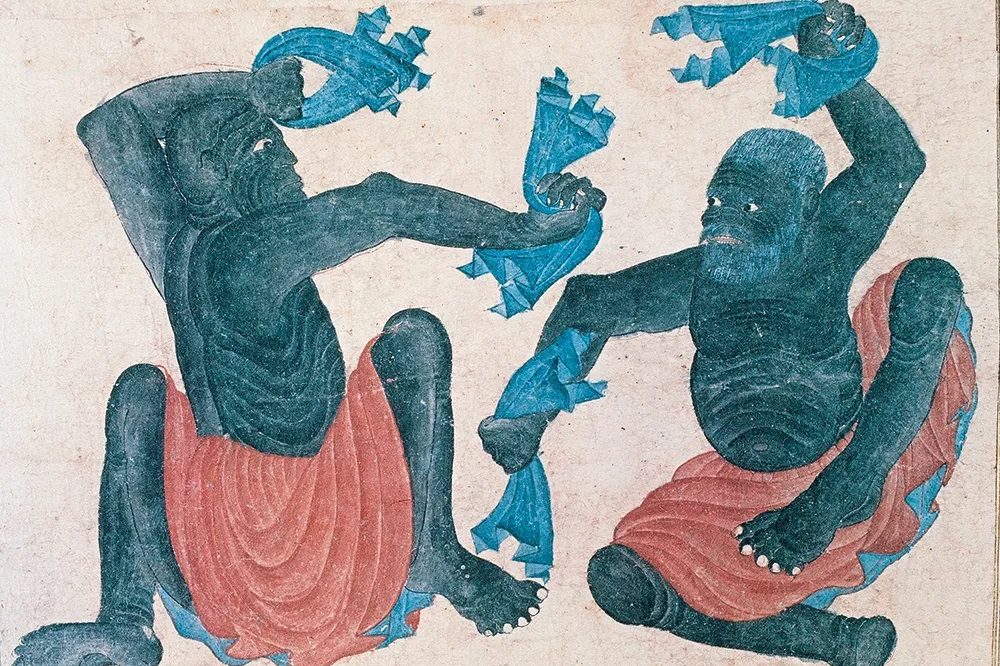

Moroccans are an extraordinarily proud people who, in addition to valuing tourism for its economic potential, genuinely enjoy sharing their country and culture with others. Morocco is mostly comprised of two distinct peoples: the indigenous Berbers and the migrant Arabs. Although Moroccans say they can immediately tell the difference between a Berber and an Arab, there was no tension or resentment between the groups. One of our Berber guides explained to us that the Berbers all speak Arabic, but not many Arabs speak the Berber language. When we asked if that bothered him, he replied, “No, Berber is hard.” Unlike in America, where annoying college children cry about oppression and colonization that was ubiquitous throughout world history, Moroccans also don’t seem to hold resentment toward their French and Spanish colonizers, instead viewing the cultural and architectural influences of this unique history as yet another point of pride. (This doesn’t mean they love the French tourists, who were overwhelmingly snobby and rude. Sorry, but it’s true.).

On our last day in Morocco, our driver, Abdellatif, had a surprise for us. He drove us to a local family’s ranch near Sidi Kaouki. Once inside, a woman who spoke no English dressed us in traditional Berber wedding clothes. We took new “wedding photos,” including some of us pouring the universal symbol of hospitality: Moroccan mint tea. It was a special experience and a very thoughtful way for Abdellatif to share his culture with us. Later on that day, we explained the American concept of “cultural appropriation” and the Halloween-related catchphrase “my culture is not your costume.” He was horrified by the idea that offense could be taken at the sharing of culture.

Morocco seemed to be the melting pot that we were promised America would be. Different groups retained their cultural practices and traditions, but the country is united under the same set of basic values: religion, family, community and patriotism. In America, we all seem to operate under a different set of values these days. Religiosity is declining, so faith in God is no longer a unifying principle. Communities are fractured and hollowed out by the offshoring of manufacturing jobs, drug and alcohol addiction, the decimation of small business and migration to big cities. Families no longer reign supreme as we embrace hyper-individualism and reject marriage and children. Most young people are taught in school to hate our country and believe it is evil. Americans increasingly replace what once united us with subjective and relative views of the world and our place in it.

This no doubt contributes to the fact that the Moroccan people generally seemed much happier while having much less. Despite America being the wealthiest country in the world and its citizens having a higher standard of living than at any time in history, we increasingly abuse substances, have high levels of anxiety and depression and have a suicide rate that is twice that of Morocco. When we took a sidecar tour through Marrakesh, our French guide told us that he is from Paris and used to be a lawyer. He moved to Marrakesh seven years ago and quit his job to run a Riad with his wife and give sidecar tours part-time because he likes riding motorcycles. He makes a lot less money, but gets to spend more time with his family and enjoying life.

That’s not to say that Morocco is a perfect country by any means: there is a lot of poverty and unemployment, women are not always treated with respect, the approach to food safety leaves a lot to be desired — and man did I miss American public restrooms. The people we met on our honeymoon, though, demonstrated the importance of shared values and the power of finding joy in simple, non-material things. That is an art that we are losing back home.

Leave a Reply