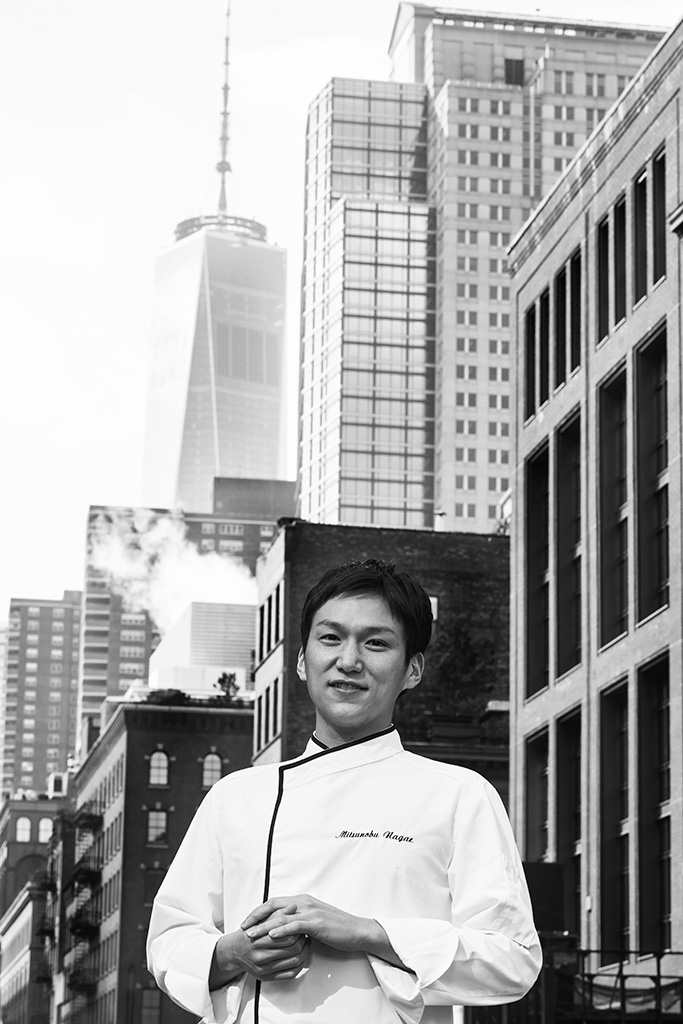

When New York City restaurants closed their doors in March 2020, Rahul Saito and his husband Howard Chang took a radical step. They brought the dining-out experience home, hiring Mitsunobu Nagae, then the chef de cuisine at the Michelin-starred Shun, to prepare weekly dinners in their Manhattan apartment.

The food was unfussy, yet profound. “There was a gazpacho, very simple, a cherry gazpacho,” recalls Chang, thirty-two. “It felt like something you could make at home, but the taste and depth was something I’d never experienced. That’s when I was like: This guy really has something.”

Inspired, Chang and Saito, who both have backgrounds in finance, approached Nagae, thirty-six, to suggest they open a restaurant together. In 2022 Tribeca’s fine dining l’abeille was born.

Now Nagae’s responsibilities have expanded once again. In August, l’abeille à côté opened next door. While l’abeille serves an extravagant chef’s tasting menu, l’abeille à côté is more informal, but retains the same DNA: namely, French cuisine with a Japanese flourish.

Critically, Chang and Saito, who have lived in Tribeca for seven years, wanted to create a neighborhood stalwart to share with family and friends.

“L’abeille has always been [focused] on gastronomic experience — that resulted in the neighbors basically saying: ‘Look I love this, I can’t eat this everyday,’” notes Saito, forty-four, who grew up in New York, but is half Japanese.

By contrast, l’abeille à côté offers something “a little bit more casual, approachable, a daily easy-going place in the neighborhood yet with [an] elevated experience… It’s not a bistro, it’s not a wine bar. It’s elegant, it’s nicely put together but not stuffy and is always available.”

“It’s very rare to have this small community and that makes us really feel strongly about this corner of Tribeca,” he adds.

The gamble has paid off. On a recent sultry August night, the intimate twenty-seat-restaurant heaved with diners, who spilled onto tables lining the cobblestone street outside. Chefs in an open kitchen prepared everything from American wagyu beef ribeye steak (sourced from Snake River Farms) to crispy takoyaki fritters. Servers, dipping and diving between tables, wore designs — dark navy jumpsuits in cotton twill for women and corduroy pants for men — created by Tribeca local Alex Drexler, founder of Alex Mill.

Nagae became interested in cooking at the age of fifteen, when he prepared the school lunchboxes for himself and his sisters in his hometown of Osaka, Japan (his father worked in a wholesale footwear company, while his mother worked for a jewellery maker). In 2007 he moved to Lyon as part of the program at Osaka’s Tsuji Culinary Institute and in 2014 landed his first job at the three-Michelin starred Le Doyen, before moving back to Tokyo to work with Joël Robuchon.

Given his experience across cultures, l’abeille à côté provides a chance for experimentation — and a fair bit of playfulness.

In a particularly whimsical twist, the seabass is served inside taiyaki shells, a Japanese fish-shaped sweet cake, usually filled with red bean paste and hawked in street stalls. The fried chicken, meanwhile, is marinated in buttermilk, garlic, ginger and fermented Korean chili paste, before it is battered in Japanese potato starch, double fried in honey and seasoned with Japanese togarashi pepper. The dish merges the techniques “taken from the best of Japanese, Korean and southern fried chicken,” says Nagae.

Savoury ice creams are a signature. At l’abeille this has stretched to black truffle, white asparagus and even onion ice cream. At l’abeille à côté, Moroccan zaalouk — an eggplant salad that mixes tomato, shallots, garlic, cumin, and coriander — is served with grilled eggplant ice cream and topped with salty jamon serrano. It’s deceptively complex, with the ice cream adding a cold, velvety counterpoint to the fragrant mix of herbs. It’s all about creating texture — not to mention an element of surprize. As Nagae puts it: “The savory ice creams add ‘temperature’ as a different dimension to the dishes.”

In French, “l’abeille” translates as “the bee.” It is a play on Nagae’s first name Mitsu, which, in Japanese, means honey. But it could also be read as more literal wish fulfilment. L’abeille à côté is ambitious; striving for comfort and coziness and, simultaneously, wanting to push boundaries.

Saito believes it’s a winning formula. Looking back at the pandemic — when restaurants went dark and he first hired Nagae as a private chef — he realized that the spots that survived “had strong neighborhood support, which helps them keep going through a difficult time.”

Like honey to a bee, l’abeille à côté, he hopes, will be just as tenacious.

Leave a Reply