It takes only a couple of hours by train from the southern reaches of rural Lincolnshire to central London. But for seventeen-year-old Bernie Taupin, leaving home in June 1967 to try his luck in the big city, the journey might as well have been to a distant planet, such was the gulf between his life as a casual farm-laborer and his ambitions to become an internationally acclaimed songwriter like his heroes Hank Snow or Merle Haggard.

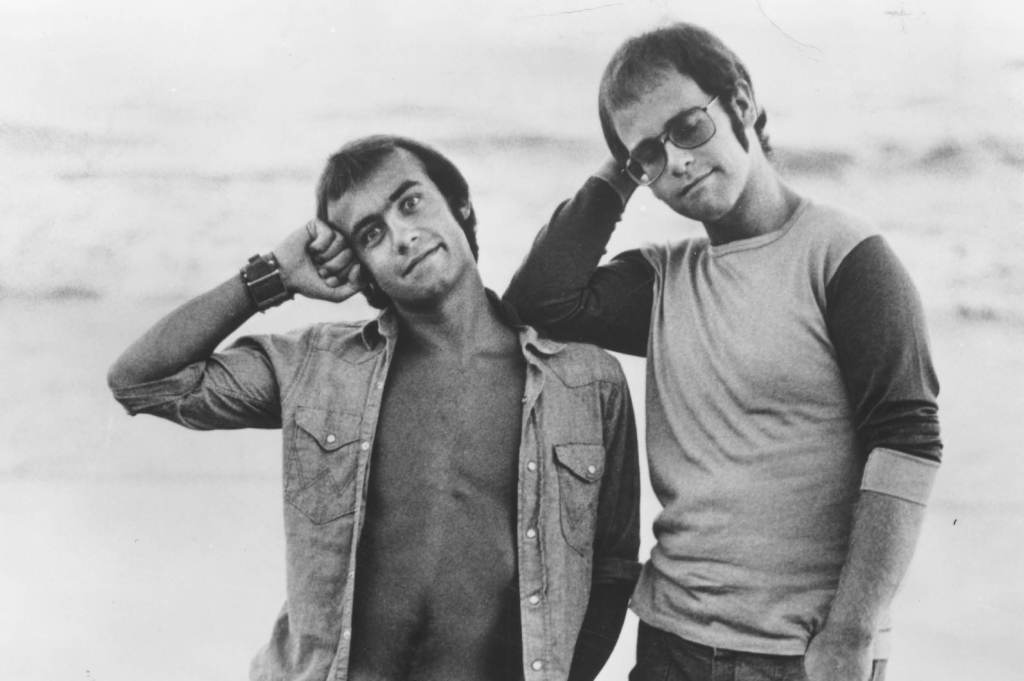

The twin spurs for Taupin’s move were a particularly nasty outbreak of fowl disease back on the farm (“maggots crawling everywhere in the burst cavities of putrid birds,” he writes, which on reflection may not be too different from the showbusiness world after all), and an ad in the weekly New Musical Express inviting aspiring writers to submit song lyrics. In due course, this led to a meeting with a twenty-year-old suburban-London pub piano player named Reg Dwight — Taupin describes him as “refreshingly square, chunky with Buddy Holly glasses and a kind face” — whom the world now knows as Elton John.

In one of those implausible plot twists largely shunned in fiction, but quite prevalent in the pop industry, the fitfully-employed pianist and his teenaged muse would go on to virtually create an entire songwriting genre. But it was a slog at first, at least up until one wet Monday morning in October 1969, when Taupin awoke in the bunk bed he now occupied in the Dwights’ cramped family home and in ten minutes flat knocked out the lyrics to a number he called “Your Song.”

In short order, Reg sat down at the upright piano in the front room and provided the accompanying melody, and between them the boys had written their first international smash while their tea was still warm on the breakfast table. Taupin was just nineteen. “It might sound like an oxymoron, but there was a simple complexity to it that completely mirrored my own adolescent turmoil,” he writes here, displaying the mixture of becoming modesty and occasional self-consciousness that characterizes the book as a whole.

Things really took off for the duo the following August, when Elton played an ecstatically received six-night residency at the 500-seat Troubadour Club in Hollywood. Neil Diamond introduced the unlikely-looking British newcomer; other attendees included sundry Beach Boys and Eagles, and the full Crosby, Stills and Nash triumvirate. But perhaps the one really imperishable thing Elton did that week was to be sitting, or rather gyrating, in front of his piano when the venerable Los Angeles Times critic Robert Hilburn walked in.

“Rejoice!” Hilburn announced in his review, which among other things praised Taupin’s lyrics as “superb,” and “capturing the same timeless, objective spirit of the Band’s Robbie Robertson,” which was rich stuff at that time. Hilburn concluded by saying of both visiting Brits that they were going to become among “rock’s biggest and most important stars.” It was a dream come true for the pair, and Taupin, still “busy shoveling shit on the farm” only a couple of years earlier, goes on to devote a dozen pages to his first impressions of the simultaneously appalling and seductive sights and sounds of LA, the city whose more congenial suburbs he still calls home today.

How did it all go right? First, there was Elton himself, then a svelte, gravity-defying sparkplug of a performer whose con- certs combined some of the deft tunefulness of the Beatles with the joyful derangement of Little Richard. Underneath all the (even then) silly costumes and glasses, it was possible to discern the old-school musician with an ear for a pop hook unrivaled since Paul McCartney in his prime. Those were the days when people in their millions actually went out and bought vinyl records and bore them home again to be ritually unwrapped as excitedly as exploring a new lover, and Elton and Bernie reaped the rewards accordingly. Here’s one of the former’s representative diary entries, both mundane and preposterous, from 1973: “Woke up, watched Grandstand. Wrote ‘Candle in the Wind.’ Went to London, bought Rolls-Royce. Ringo Starr came for dinner.”

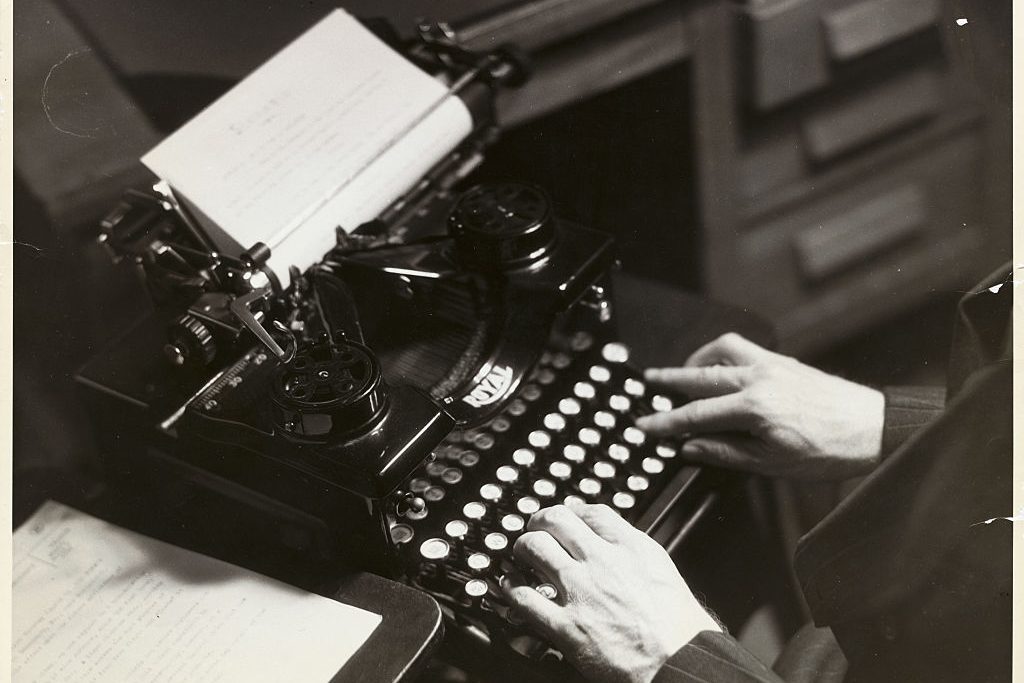

The other key ingredient of their success was Taupin’s wistful and sometimes mildly trippy lyrics, full of faded cowboys and maudlin astronauts, perfectly formed vignettes that at their best read like something Baudelaire might have dreamt up had he somehow first listened to Sgt. Pepper. Bernie and Elton were the perfect mix; the former couldn’t write music, and the latter couldn’t write words. They always worked separately. Taupin would post (later fax) a page or two to the studio, where the Rocket Man would prop them up on his keyboard and swiftly compose a “Daniel” or a “Tiny Dancer,” or, for that matter a “Candle in the Wind,” which we learn here was initially intended as a eulogy to the late actor Montgomery Clift, not Marilyn Monroe. “The celluloid nirvana she inhabits was never my thing,” the author confides.

There would be a few clunkers along the way, too, among them the seasonal “bonus” track to 1974’s Caribou album (“Step into Christmas, let’s join together/We can watch the snow fall forever and ever”). But for real indignity there were Taupin’s lyrics to 1985’s “We Built This City” by the band Starship, which emerged from the ashes of Jefferson Airplane, with its catchy refrain, “Marconi plays the mamba/Listen to the radio/Don’t you remember?/ We built this city/We built this city on rock and roll.” Well, quite — although as Taupin unanswerably says, “It may have been voted the worst song of all time, but since it also went straight to number one it’s been quite good to me.”

When Elton himself periodically disappears from the story, we’re left with a parade of celebrity encounters with the likes of Princess Margaret, Salvador Dalí, Graham Greene, Hugh Hefner and sundry Beatles and Stones, which isn’t bad for the boy from the Lincolnshire farm. The drugs and booze, and the somehow familiar uplifting path to recovery, are all here too, although to be fair to Taupin he rarely blames, whines or emotes; he’s a lucky if undeniably talented soul, and he knows it.

He’s also an unlikely fit with the cheerfully banal world of rock and roll. “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters,” from Elton’s 1972 album Honky Château, which I think his best lyric, is so vivid and convincing in its description of New York, then as now both so fascinating and hideous to visitors, that it’s easy to forget Taupin was barely twenty when he wrote it, on his first ever night in the city, crammed into a “grubby, cigarette carton-shaped” Times Square hotel listening to all the wailing sirens on the street. Sometimes it takes an outsider to cut through to the essence of a place. That sense of looking in is a through- line to Scattershot; it sets the author apart, a little to the left, a little above, an unusually perceptive and relentlessly literate Englishman abroad.

Here are some other points that emerge from the pages of Taupin’s agreeably non-linear autobiography: the author might be mildly OCD, still enjoys a martini, loves trucks and dogs, hates clowns and circuses. He’s been married four times, and once released a spoken-word album whose delivery a critic described as having the “same energy level as a priest during a dreary weekday Mass.” Set against this, he also once produced an album called American Gothic by the singer-songwriter David Ackles that the London Sunday Times called “the Sgt. Pepper of folk.” The man of real talent who longs to be acclaimed for something else is a recurring and often quite endearing figure in the arts, and sure enough Taupin speaks at some length here about his bold, multimedia sculptures and paintings, many of which feature renditions of the American flag in unconventional settings.

The general tone of Scattershot is conversational, wryly self-deprecatory and, as the title implies, just slightly rambling. Though generally engaging, it’s not entirely fault-free. Even in these debased days, it comes as a surprise to learn that neither the Oscar-winning wordsmith nor any of his editors appear able to distinguish between “stationery” and “stationary,” a lapse which rather mars the punchline of one of Taupin’s best jokes, while just on a technical note it seems odd that the author might be eulogizing the band Black Sabbath in the summer of 1967 when that great combo first traded under the name only two years later. But these are trifles when set against the book’s many charms, chief among them its unvarnished view of the shark-filled waters of the 1970s music business.

At the end of the day, it’s hard not to be disarmed by Taupin’s confessions of his struggles with the bottle (at one point he named his dog Vodka) and other substances, his philosophical acceptance of his good fortune and his obvious if not uncritical affection for his adopted country. The book is refreshingly free of sentimental clutter, but it would take a heart of stone not to be moved by the takeaway message of a shy boy’s progress from the grim austerity of postwar provincial England to the proverbial mansion on the hill in California.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.