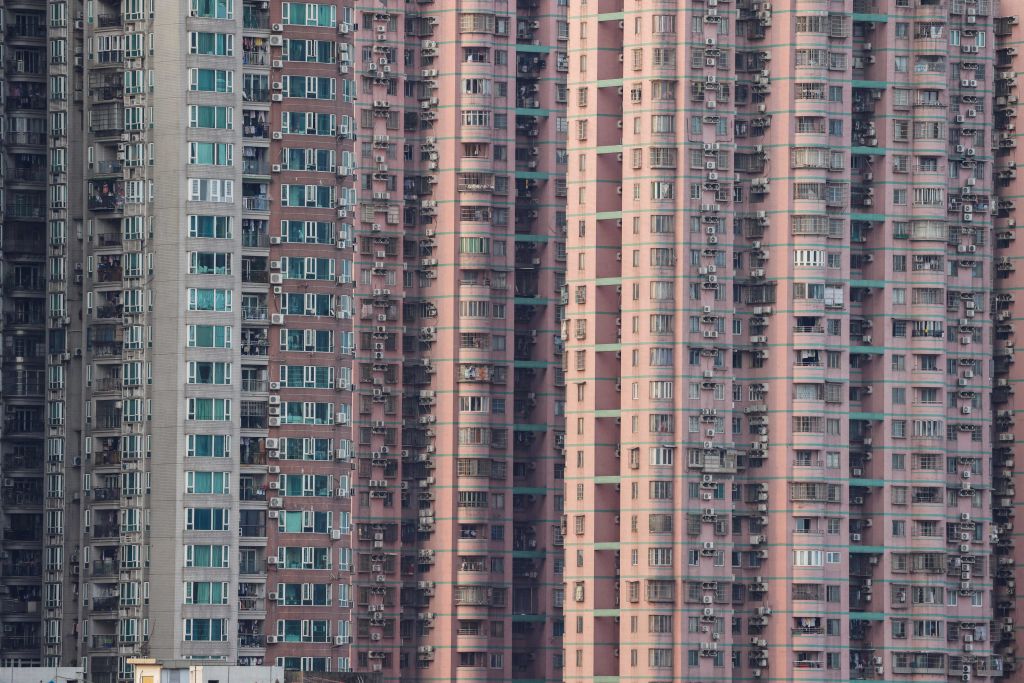

Once, not that long ago, few people outside China had heard of the property developer Evergrande. Now it is synonymous with failure, debt and loss — and seen as the tipping point in China’s real estate market three years ago. Now meet Country Garden, another large property developer, hailed even a year ago as a model “corporate citizen.” As of this week, it is a penny stock facing a debt and liquidity crisis, cannot service its US dollar debt, and is on the brink of default. Its financial demise is not quite on the scale of Evergrande, but it comes at a worse moment, when China’s economy is in the eye of a bad economic news storm, consumer and business confidence are fragile, and when the word “contagion” has resurfaced.

The bigger story is that China’s development model is no longer fit for purpose, and hasn’t been for some years

Country Garden and Evergrande are the highest profile failures in China’s beleaguered real estate sector, in which companies like these, accounting for two fifths of Chinese home sales, have defaulted. Country Garden has liabilities of around $190 billion, compared to $300 billion for Evergrande, but also has over 3,000 projects across China, or four times as many as Evergrande. If Country Garden has to write off unsold or uncompleted homes, or if prices fall even more significantly, there will be greater contagion risk.

China’s official house price data isn’t wholly reliable because it is based on surveys rather than transactions. Recently published numbers though suggest that existing house prices are down by 15 percent compared with 2021. New home prices are said officially to have dropped by about 2.5 percent compared with 2021, but there is plenty of uncertainty about whether this reflects actual prices.

Because of the significance of real estate in the Chinese economy — it is thought that maybe as much as two fifths of the collateral behind loans in the entire financial sector is linked to property — the danger of contagion is never far away.

As if to underscore the point, the ratings agency Moody’s said this week that the number of non-performing loans at Chinese banks had more than doubled because of the housing developer crisis. Trouble is brewing, moreover, in a little understood part of the financial sector. The $3 trillion, loosely regulated, trust bank sector pools the savings of households, and then invests and lends their money to a range of assets, including real estate. It then pays a high rate of interest to its customers.

The subsidiary of one of the largest such asset managers, Zhongzhi, suspended payments to investors this week on some of its 270 products, much to the chagrin of its angry investors. Trust banks work like a Ponzi scheme, paying attractive rates of interest to existing investors by constantly raising money from new investors. For this firm, the music finally stopped.

Partly to address the contagion risk head-on, China’s central bank has cut interest rates and added liquidity to help relieve the financial stress. But even if the authorities are able to keep the financial disturbances limited, losses in the property sector and the risk of financial instability can cause contagion in other ways. There may well be a flight to safety, for example, as people hoard cash in banks they consider safe or as they sell assets to buy government bonds. This would mean that credit conditions tighten for private companies and household borrowers, which are precisely the hard-pressed constituencies that the government wants to lead the economy out of the doldrums.

The unfolding problems in property and finance are the proximate cause of China’s current economic hiatus, but the bigger story is that China’s development model is no longer fit for purpose, and hasn’t been for some years. As many people now recognize, China is flush with excess debt, has poor demographics and productivity, weak governance and a politicized business environment. Against this backdrop, it is clear that the government faces a huge challenge. But it also seems to be at a loss about what to do about it.

Its current solution — lower interest rates, more liquidity, a weaker currency and the relaxation of rules and regulations for homeowners, developers and business — are all very well, but they are more of a band-aid than a durable solution. China’s problems aren’t just little mistakes that can be tweaked or reversed — they are systemic in nature. And the government is fully committed to the economic and political repression that make these problems impossible to fix.

Perhaps, before too long, the government will decide to stimulate the economy more, even if that risks adverse debt consequences. But it is becoming more and more evident that it wasn’t just the real estate sector that reached a tipping point three years ago — it was China’s whole economy.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.