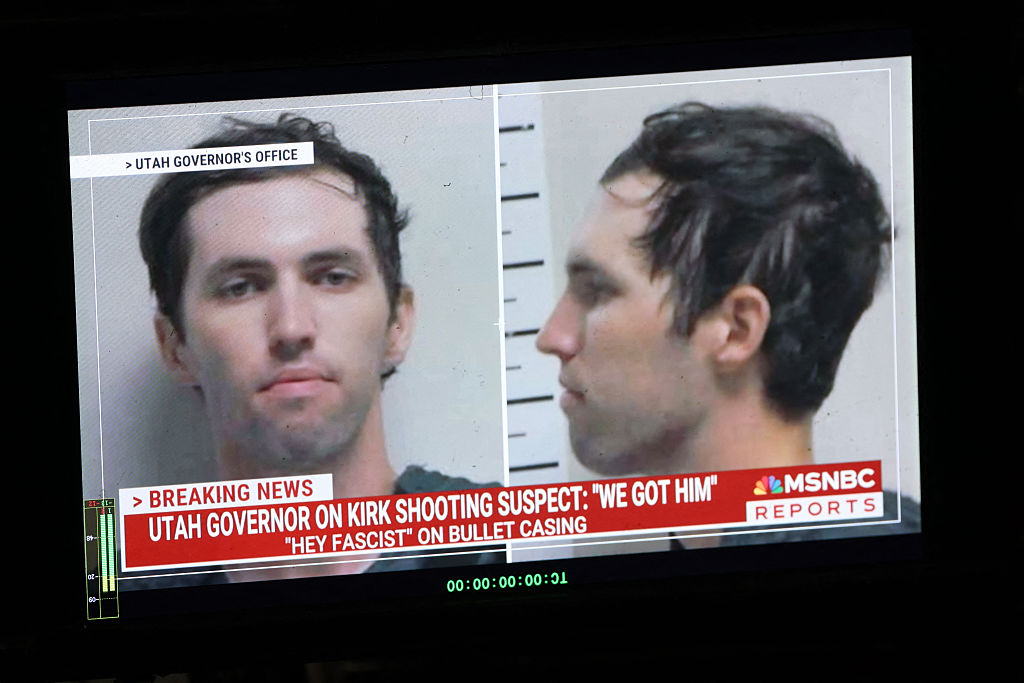

The federal courthouse in downtown Portland has become ground-zero for the nightly orgy of assaults, looting, arson, and public nudity — and, most recently, a surrealistic duel between protesters and federal agents using leaf-blowers to drive back each other’s tear gas — that continues to enliven America’s so-called Rose City in the wake of the death of George Floyd.

It’s a curious thing, this new alignment of some of America’s most high-profile mayors with the very people burning down their towns. In Portland the competent authority figure is 57-year-old Ted Wheeler, who took office three-and-a-half years ago. By law, all Portland mayors are nonpartisan, but it seems unlikely Wheeler will be out campaigning this fall for the Trump-Pence ticket. Like many mayors, he’s expressed the great orthodoxy of the past two months, announcing that he plans to redirect $7 million from his police budget and $5 million from other city funds to ‘communities of color’. But Wheeler doesn’t stop at merely repeating the current Black Lives Matter slogans. He’s actually out there on the barricades, standing on the courthouse steps last week to express solidarity with the protesters and berating the federal agents sent to his city.

‘If they launch the tear gas against you, they’re launching the tear gas against me,’ Wheeler shouted over his surgical mask. ‘We are a community… We demand that the federal government stop occupying our city.’

Since the mayor was met by signs in the crowd that read ‘Tear gas Ted’ — in response to allegations that he had allowed police to use tear gas against protesters before federal agents arrived — and a large banner unfurled immediately behind him that abandoned subtlety for the stark message ‘Fuck you Wheeler’, this exercise in outreach could be called only a mixed success. Whatever else you can say about the political dislocation of America’s Richard Nixon years, what we have now is the crack-cocaine version of it. Wheeler ‘made a fool out of himself’, President Trump told Fox News. ‘He wanted to be among the people so he went into the crowd and they knocked the hell out of him. That’s the end of him.’

It goes without saying that Mayor Wheeler is a case study in privilege. Born into a wealthy Oregon tree-farming dynasty, he went on to study economics at Stanford, business at Columbia and public policy at Harvard. His father Sam was one of those hardy frontier types who embodied so much about the old Pacific Northwest — a logger who rose to be vice-president of a Fortune 500 company, and a self-confessed blackout alcoholic. Ted Wheeler would later remember being taken as a teenager to dinner in a restaurant, ‘where my Dad got louder and louder [until] finally the lady next to us leant over to her husband and said, “That man is drunk”’. ‘It wasn’t pretty,’ Ted remarked. ‘My dad was completely intoxicated.’

Of course, there were consolations. Young Wheeler could spend his summers traveling abroad, or visiting the small coastal town full of neat clapboard houses and fluttering American flags that bears his family name: Wheeler, Oregon.

In 1993, as a 31-year-old recent Harvard graduate, he published a 200-page manifesto called Government That Works. ‘The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present,’ Wheeler wrote, quoting Lincoln. ‘As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.’ Later that year Wheeler stood for election to the Boston city council, finishing second to last among 13 candidates.

After that Wheeler put politics aside and spent 10 years working in financial services. While his subsequent résumés have included such details as his trips to Mount Everest, they’re strangely quiet about his years of toiling in the financial vineyards.

Six months ago Wheeler announced that he was parting from his wife of 15 years, Katrina. In the unique manner of American political discourse, there was an air of almost Edwardian restraint to their treatment in the mainstream press, with a noticeably more robust line taken on social media and elsewhere. The Wheelers were frequently subjected to homeless protesters camping outside their main Portland home, an issue more than once requiring a police response.

Wheeler’s time in office has largely been distinguished by ambivalence. Clearly a candidate for inclusion in the ‘effete corps of impudent snobs’, as Spiro Agnew once put it, he’s also been praised for his attempts to cut waste from his state budget. One of his longtime advisers described him to me as a ‘natural conservative, in that he loathes unpredictability’, while another associate with a sideline in mental health added: ‘Ted has a permanent apparatus of self-containment about him. In many ways he’s the classic alcoholic’s kid: they keep things buttoned up, frequently seek approval and affirmation, and tend to overreact to situations beyond their control.’

[special_offer]

It’s fair to say that both sides of Ted Wheeler were on display in the early hours of last Thursday in downtown Portland. On the one hand, there was the doughty public official who dared to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the protesters facing off against federal agents on the courthouse steps, and getting tear-gassed in the process. ‘It’s hard to breathe,’ Wheeler evocatively said of this experience. ‘I saw nothing which provoked this response. I’m not afraid but I am pissed off.’

On the other hand there was the trust-fund kid whose speech earlier that evening appealing for solidarity against Trump’s stormtroopers was rudely interrupted by hecklers impatient at the speed of his plan for depolicing Portland, causing him to cut short his prepared remarks and temporarily retreat inside, accompanied by his private security detail. Once there, I’m told that the mayor’s mask of imperturbability slipped. ‘Fucked again,’ he groaned.

Perhaps in the end November’s election will come down to the spectacle of one millionaire tycoon, still trying to resolve his relationship with his late father, squaring off against another one to decide who really governs America.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.